Persecution and Apology in Brazil / Brazil Apologizes for WWII Anti-Japanese Persecution; 2015 Documentary Helped Victims Break Their Silence

Filmmaker Mario Okuhara delivers a speech at the Amnesty Commission in Brasilia on July 25.

14:14 JST, September 4, 2024

This is the first part of a two-part series on the Brazilian government’s recent decision to apologize for the persecution of Japanese immigrants and their descendants during and after World War II.

Brazil is home to the world’s largest community of citizens of Japanese descent, comprising about 2.7 million people.

In July, the Brazilian government attempted to heal an 80-year-old scar by acknowledging and officially apologizing for persecution suffered during and just after World War II by the group, often referred to as Nikkei or Nikkeijin.

What transpired for Brazil to finally own up to such a dark stain on its history after so many years? The Yomiuri Shimbun set out to find out.

***

“Brazil had an opportunity to correct a historic mistake,” Japanese Brazilian filmmaker Mario Okuhara, 49, said with his face showing deep emotion. “Horrific acts cannot be erased, but we can learn from these sorrowful episodes and prevent them from happening again.”

Okuhara, who produced a documentary about the past mistreatment of people with Japanese heritage, was addressing a meeting of the Brazilian government’s Amnesty Commission in Brasilia on July 25.

After Okuhara’s speech, Enea Almeida, chair of the commission, detailed eight categories of violations that occurred, such as torture and discrimination. She then concluded by saying in Japanese, “The Brazilian government seeks forgiveness for the persecution of your ancestors.”

Okuhara called for an official apology from the Brazilian government in 2015. He brought the past persecution of the Nikkeijin to light in 2012 with the release of his documentary titled “Yami no Ichinichi” (A Dark Day), which featured extensive interviews with victims and others.

Japan was among the Axis powers, along with Germany and Italy, that were defeated by the United States, Great Britain and their allies in World War II.

After the war ended in 1945, the Japanese community in Brazil, lacking access to accurate and reliable news, was divided between “winners” who stubbornly believed that Japan had been victorious in the war, and “losers” who acknowledged Japan’s defeat.

The division led to intense violence between the factions, leaving 23 dead.

Brazilian authorities, citing security reasons, designated the “winners” as “fanatical terrorists” and shipped 172 people to a penal colony on Anchieta Island off the coast of Sao Paulo state.

The island, about 6 kilometers offshore, was surrounded by shark-infested waters, making escape all but impossible. Anchieta was where the most dangerous criminals were sent.

Okuhara’s film begins with testimony from a man in the “winners” faction.

“They were innocent,” the man said about the majority of detainees. “They were only sent there because they refused to step on the Japanese flag or a picture of the Emperor in the police station.”

The film was screened throughout Brazil, raising awareness among Brazilian society of the country’s past history of persecution.

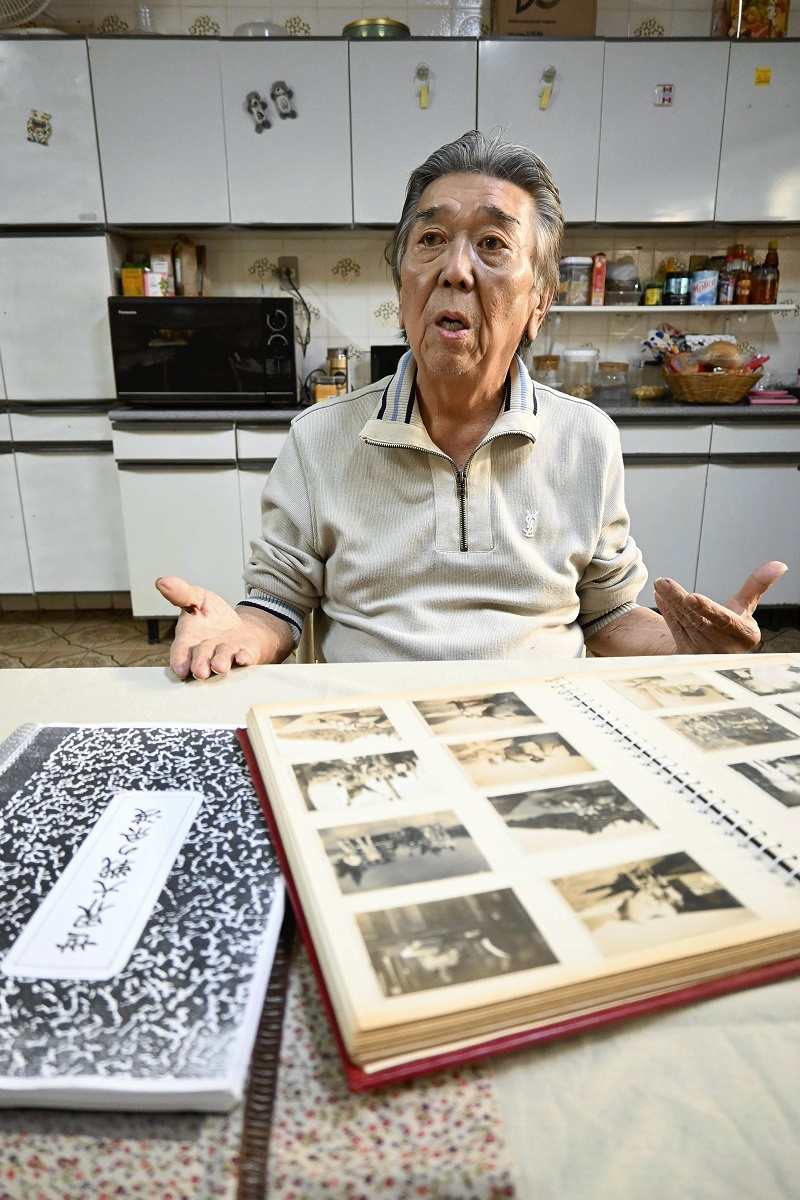

Akira Yamauchi speaks about the hardships suffered by his grandfather and father at his home in Sao Paulo.

Akira Yamauchi, 75, a Nikkei resident of Sao Paulo state, said his father, Fusatoshi, was a central figure among the “winners” and was sent to Anchieta Island along with his grandfather, Kenjiro. The crime: refusing to step on the Japanese flag or Emperor’s picture.

“I was unlawfully imprisoned and subjected to the greatest pain and humiliation without any clear violations,” Kenjiro wrote in a diary about his imprisonment.

Said Akira: “For both of them, the flag of their native land was the same as their life. To step on it would have been an unfathomable humiliation.”

The majority of the detainees remained imprisoned for over two years. After returning to their homes, they said nothing about the ill treatment they experienced in prison, not even to their families.

Okuhara, who interviewed hundreds of people including former prisoners, said he felt their reluctance to address a subject that for them was taboo.

Akio Hidaka

Tokuichi Hidaka, 98, finally opened up after several years of persuasion by Okuhara. His second son, Akio, 60, told The Yomiuri Shimbun, “At home, my father never talked about his incarceration, and never divulged his true feelings to the family.”

Discrimination against Nikkeijin intensified during World War II and continued after it ended. Many people remained afraid to mention the hardships they encountered for fear of making things worse. They thought it was better to stay silent.

“That it was best to keep from being ostracized again was the common sentiment among [those] who faced discrimination during and after the war,” said Lidia Yamashita, a Nikkeijin who is chairperson of the governing board of the Historical Museum of Japanese Immigration in Brazil in Sao Paulo.

With the Nikkei community undergoing a generational change, there are growing calls to face up to the injustices of the past.

The Brazilian government is also changing its own perception of history. After announcing the official apology, the Amnesty Commission’s Almeida said she was deeply grateful that Brazil is able to pass knowledge of this history on to a new generation for the purpose of respecting human rights and diversity.

Promotion of migration

The Japanese government initiated a program of emigration to Brazil to alleviate high unemployment and other societal problems following the Russo-Japanese War. In 1908, the Kasato Maru sailed into Santos Port outside Sao Paulo, carrying the first 781 Japanese migrants.

In 1924, a restrictive new U.S. immigration law barred Japanese immigration to the United States. From then, the Japanese government promoted emigration as a national policy, resulting in about 189,000 people relocating to Brazil prior to the war.

After the outbreak of the war, Brazil and Japan severed diplomatic relations and migration halted. The two countries restored formal ties in 1952, after which about 68,000 people emigrated from Japan to Brazil.

Top Articles in World

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation

-

North Korea Possibly Launches Ballistic Missile

-

10 Universities in Japan, South Korea, Mongolia to Establish Academic Community to Promote ICC Activities, Rule of Law

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation