30 Years After Sarin Attack — Lessons Learned / Aum Successor Groups Persist, Fueling Concern of Enduring Cult Devotion

Investigators from the Public Security Intelligence Agency enter an Aleph-related facility for an on-site inspection Feb. 13.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

7:00 JST, March 22, 2025

This is the third and final installment of a series that examines the scars left by the Aum Supreme Truth cult’s chemical attack on the Tokyo subway system on March 20, 1995, and explores the lessons learned from that tragedy.

***

The continued operation of successor groups to Aum Supreme Truth, despite organizational changes, raises significant concern about the enduring devotion of members to the former cult leader.

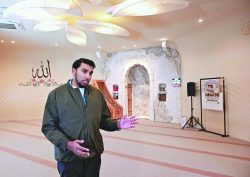

“This is an on-site inspection by the Public Security Intelligence Agency. Please cooperate,” an investigator from the agency said using a megaphone to call out loudly in front of a facility of Aleph in Adachi Ward, Tokyo, on the afternoon of Feb. 13.

The four-story concrete building of Aleph, the primary successor to Aum, had no nameplate, and most of the windows had closed curtains. The perimeter was surrounded by a temporary wall about 2 meters high, and numerous security cameras were pointed toward a public road and other areas.

About 20 minutes after the announcement started, individuals emerged from inside the facility. “What are you here for?” one of them asked, expressing dissatisfaction and pointing a video camera at the authorities. Subsequently, 12 investigators entered the building one after another.

During the 3.5-hour inspection, a photo of Chizuo Matsumoto was found in the training hall. Matsumoto, the Aum founder and also known as Shoko Asahara, was executed in 2018.

“The essence of Asahara worship remains unchanged,” said Shuhei Yokoyama, 69, the chairman of a residents’ council formed to counter Aleph. “We cannot feel safe until this group disbands because we don’t know when they might become violent again.”

Aum Supreme Truth perpetrated a series of heinous crimes, most notably the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack, the 1989 murder of lawyer Tsutsumi Sakamoto and his family, and the 1994 sarin attack in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture.

In 1995, the cult was ordered to dissolve under the Religious Corporations Law, and it had its official religious corporation status revoked. Despite this legal mandate, members persisted in the group’s activities as a voluntary association.

Following the dissolution order, the group underwent several name changes, split and branched out. Currently, Aleph, Yamadara no Shudan and Hikari no Wa remain active, all maintaining Asahara’s ideological influence. Since 2000, these organizations have been subject to ongoing surveillance by the Public Security Intelligence Agency as part of regulatory measures.

A Buddhist painting believed to depict Shoko Asahara is seen in Aleph’s training hall during the on-site inspection on Feb. 13.

Although on-site inspections have been conducted and these groups are legally required to report their membership and assets, the legal framework lacks coercive powers, preventing the seizure of evidence.

After 25 years of monitoring, the effectiveness of these measures has diminished, making ongoing surveillance increasingly challenging.

Aleph’s reported assets have plummeted from about ¥1.29 billion in February 2019 to a mere ¥8 million in February 2024. The Public Security Intelligence Agency suspects that the group’s members are transferring assets to affiliated corporations controlled by Aleph’s leadership.

According to an agency official, despite the presence of Asahara-related photos and teaching materials in Aleph facilities nationwide, followers consistently conceal their true beliefs and activities during inspections.

Communication records between followers are believed to be stored in cloud-based internet services, making them difficult to confirm during inspections.

“We fear that we may not be able to grasp their movements if the current situation persists,” one senior agency official said.

Yuji Nakamura, 68, a lawyer who has long represented the families of the victims, said during a press conference on March 12: “I never imagined they would remain this active past 25 years.”

The Aum Supreme Truth victims’ support organization, where Nakamura serves as vice chairman, is attempting to enforce a 2019 court ruling that ordered Aleph to pay over ¥1 billion in damages. However, these efforts, which rely on compulsory seizure procedures, are facing significant obstacles.

Collecting the amount requires definitively proving that the assets in question belong to Aleph. To date, only about ¥42 million has been successfully recovered.

Nakamura alleges that Aleph conceals cash in envelopes bearing the names of affiliated companies. Furthermore, he claims that the group repeatedly changes its designated representative to obstruct the delivery of court summonses, hindering asset disclosure.

During the press conference, Nakamura also highlighted the lack of a legal framework that would allow the government to initiate compulsory seizure or bankruptcy proceedings on behalf of the victims’ families.

“It is deeply disheartening that such a system has not been implemented, even after 30 years,” he said.

A security camera is seen outside the facility Feb. 13.

An Aleph official commented in an interview on March 16, “We take the incidents seriously,” and said, “We will continue to provide compensation to the victims.”

Three decades have elapsed since the Tokyo subway sarin attack. As successor organizations to the Aum Supreme Truth persist, the victims’ families continue to age.

The ongoing investigation and monitoring of anti-social religious organizations, coupled with the urgent need for comprehensive victim relief, underscore the profound lessons that society, having witnessed indiscriminate chemical terrorism, must still learn.

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Japan Seeks to Counter China's Expanding Influence in Pacific by ...

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Ch...

-

Tokyo Skytree Observation Deck Remains Closed for Inspection afte...

-

Japanese Watermelon Shipments Starts in Leading Production Distri...

-

Impact on Japanese Economy Unclear with Trump’s New Tariffs, Shif...

-

Takeshima Day: Persistently Demanding Resolution from South Korea...

-

Hanzomon Line Service Suspended between Kudanshita, Oshiage Stati...

-

CARTOON OF THE DAY (February 25)

Popular articles in the past week

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

-

Japan, U.S. Name 3 Inaugural Investment Projects; Reached Agreeme...

-

Tokyo Skytree's Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (...

-

Director Naomi Kawase's New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Ja...

-

Japan’s Major Real Estate Firms Expanding Overseas Businesses to ...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japanese Figure Skater Kaori Sakamoto’...

-

Baby Monkey Punch Captures Hearts at Chiba Pref. Zoo, on Social M...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reco...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many Peop...

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages C...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan