Rice Prices Remain High amid Scramble For Supplies; Rising Production Costs Also A Factor

A shopper passes bags of newly harvested rice at a supermarket in Adachi Ward, Tokyo, on Sept. 26. The shelf on the left is mostly empty because major brand-name rice was not available.

17:38 JST, October 4, 2024

A 47-year-old stay-at-home mom could not help but sigh as she saw the rice prices at a Benny supermarket in Adachi Ward, Tokyo, in late September.

“I have four children and our family eats through 30 kilograms of rice each month,” the woman said. “I’ve been to several supermarkets, but rice is so expensive and I can’t afford it.”

The supermarket had bags of newly harvested rice grown in Chiba, Niigata and other prefectures stacked up on its shelves, but the prices were said to be about 50% to 80% higher than last year. While shipments of some kinds of newly harvested rice have steadily arrived at the supermarket since late August, the shelf for major brand-name rice remained mostly empty.

“We’ve managed to secure supplies of newly harvested rice, but it’s expensive and hasn’t sold well,” a senior official of the company that operates the supermarket said.

Cases like this have been common in Japan this year. Rice prices have sharply increased due to factors including a fierce scramble among retailers and other purchasers to secure supplies, and have yet to come down. A rice shortage and the staple grain’s high price have put a strain on household budgets. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Minister Yasuhiro Ozato indicated at a press conference after being appointed to the post this week that he would consider reviewing the nation’s rice policies.

A rice supply shortage was the origin of the surging prices. The summer heat wave in 2023 negatively affected rice quality and squeezed the available supply. This has been compounded by consumers stockpiling rice in preparation for potential disasters. Ongoing competition among retailers and other buyers desperate to avoid running out of rice also has been a factor behind the stubbornly high prices. Although the feeling that rice is in short supply is beginning to ease, private companies that received orders from retailers have been busily purchasing stocks of rice.

Ordinarily, more than 50% of rice distributed on the market passes through the JA Group, a body of agricultural cooperatives. However, this year has been different.

A wholesaler in the Kyushu region that purchases a substantial amount of rice from JA was this year told by some of the group’s members that they could provide only about half of last year’s volume. This apparently was because private companies had been buying up rice at higher prices than JA could offer.

Govt stockpiles untapped

There had been early warning signs that a rice shortage was looming, but the government’s response was often one step behind. The average wholesale price announced by the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Ministry for rice produced in 2023 increased for four consecutive months from March 2024. Many observers even stated before summer that the price of rice has been “higher than expected.” Since late August, the government has been pressing companies and wholesalers to help improve the situation. But even when shops began running low on rice, the government remained reluctant to release supplies from its stockpile.

Supplies of rice grown in Hokkaido, a major production area, will soon start hitting the market in greater volume. “Prices will settle down to some extent from the end of October or early November,” said Yasufumi Miwa, a chief specialist researcher at the Japan Research Institute.

However, rice production costs are continuing to climb. “I doubt rice prices will return to last year’s levels,” Miwa said. “I think prices that are 10% to 20% higher than they had been previously will become the norm.”

At a press conference Thursday, Toru Yamano, chairman of the Central Union of Agricultural Cooperatives (JA Zenchu), called for understanding about the cost pressures growers were facing. “These additional costs need to be reflected in the sales price,” Yamano said.

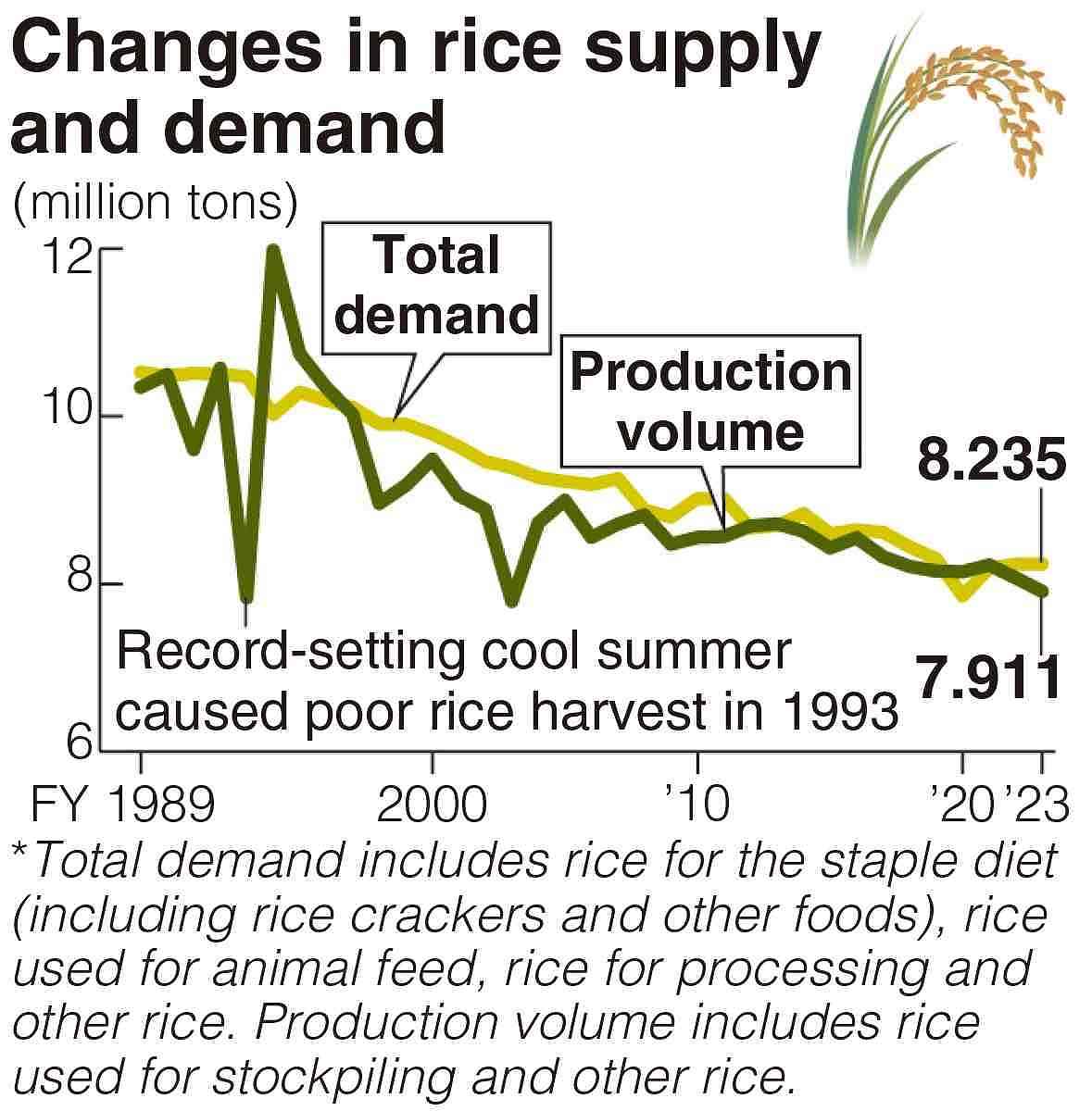

However, demand for rice is expected to continue trending downward over the long term. It is possible that higher prices could accelerate consumers’ shift away from eating rice.

Ishiba hints at production changes

The volume of rice consumed in Japan has been declining for many years as people eat an increasingly diversified diet. In a bid to prevent excessive rice production from pushing prices down, the government had adopted a policy of cutting back the acreage under cultivation. Under this policy, annual production volume targets were set and a production limit assigned to each prefecture. The policy was abolished in 2018.

However, production volume guides based on demand forecasts have been issued, and subsidies are paid to farmers who grow wheat, soybeans and rice used for animal feed instead of growing rice for human consumption. Some observers argue that this means the acreage reduction policy is effectively still in place.

The recent uproar over the cost of rice even became an issue during the recent Liberal Democratic Party presidential election, in which Shigeru Ishiba was selected as the ruling party’s leader, subsequently becoming the new prime minister. During the campaign, Ishiba indicated he would increase rice production by reviewing and effectively adjusting production levels, and would provide direct income compensation to farmers who were affected by falling rice prices.

At a press conference Wednesday, Ozato also hinted that rice policies could be set for a shakeup. “I’ll push aside all preconceptions and pursue policies that lead to higher incomes for farmers,” Ozato said. “I’ll consider ways to ensure our rice paddy policies can stably operate into the future.”

Related Tags

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan