Rising Temperatures Make Mikan Growers Switch to Avocados; Researchers, Local Govts Look to Support Changing Crops

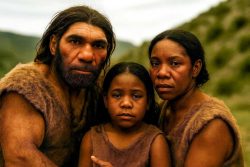

A farmer, who wants to make Shizuoka Prefecture an avocado production center, shows some avocados at his farm in Shimizu Ward, Shizuoka, on Oct. 24.

14:20 JST, December 22, 2025

Eating mikan mandarin oranges while sitting at a kotatsu heated table in a cozy living room is a classic winter pastime in Japan — but thanks to global warming, this quintessential scene could possibly vanish.

A Japanese research institute has calculated that 60% of the nation’s mikan orchards could be wiped out in 30 years if global warming accelerates more than anticipated. Some mikan farmers are already switching to growing avocados, a subtropical fruit, as they seek a new means of business survival.

In 2024, growers in Shizuoka Prefecture harvested 88,500 tons of mikan, making it the nation’s second largest producer after Wakayama Prefecture. In May, with the aim to become a major avocado production center, Shizuoka Prefecture began holding workshops offering advice and instructions on avocado growing methods. The workshops have been a hit, drawing 120 attendees, including mikan farmers.

“Farm produce across the nation is being affected by warmer temperatures, so we must take steps to address this,” an official of the prefectural government said. “We want to turn deserted farmland previously used to grow mikan and other crops into production areas for avocados.”

According to the Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Ministry, avocados can be grown in mikan production areas, which often feature a lot of hilly land. Avocados are already being cultivated in Wakayama, Ehime and Kagoshima prefectures, which are major citrus fruit production areas. In Matsuyama, the city government has taken the initiative in distributing avocado seedlings and providing technical advice to growers in a bid to develop a local avocado brand.

A 65-year-old farmer in Shimizu Ward, Shizuoka, began growing avocados five years ago. “Domestically grown avocados can be harvested when they’re fully ripe, and have a richer flavor than imports,” Uchida said proudly. The about 60 trees on Uchida’s 300-square-meter field yielded about 200 avocados last year, some of which fetched up to around ¥1,000 each.

“I hope we can develop stable production methods that will encourage young growers to confidently enter the market,” Uchida said.

Halting farmer population drop

The National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), a national research and development agency based in Ibaraki Prefecture, issued its estimates for land suitable for growing mikan and avocados earlier this year. According to NARO, if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced and average temperatures rise by 1.8 C in the middle of this century (2040 to 2059), about 30% of land currently used for growing mikan will become unsuitable for that purpose because the higher temperatures cause sunburn and damage the fruit. If emissions reach “extremely high” levels and the average temperature climbs by 2.3 C, NARO estimates that 60% of land currently ideal for cultivating mikan could be lost.

By contrast, if the average temperature rises by 1.8 C, the amount of land suitable for growing avocados would expand 3.2-fold. NARO calculates that one-quarter of land suited to growing mikan could be replaced by avocado cultivation.

Called “forest butter” because of their high content of vitamins, minerals and healthy fats, avocados are becoming increasingly popular, especially among health-conscious consumers. In 2022, about 50,000 tons of avocados were imported to Japan — more than triple that of 20 years earlier.

Classified as “subtropical fruit trees,” growing avocados in Japan had previously been limited to areas such as the temperate Nansei Islands. Only about 34 tons of domestically grown avocados were harvested in 2022, with 99% of avocados distributed around Japan grown overseas in nations such as Mexico.

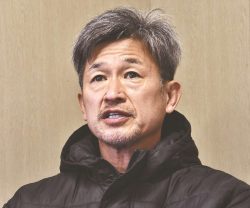

“It’s obvious that growing mikan in Japan will become more difficult in the years ahead,” said Toshihiko Sugiura, who was involved in compiling the NARO estimates.

“Avocados sell for high prices. If Japan could, say, grow even 10% of the avocados it currently imports, it would probably help to stem the decline in farmers who are struggling to find successors for their farms,” said Sugiura, an expert in agricultural meteorology. “I hope the results of our estimates provide an opportunity for farmers to consider that changing the crops they grow is an option.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Ibaraki Pref.’s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts