Kyoraku / Ginza’s Beloved Mellow Chuka Soba; Third-Generation Owner Starts Making Noodles from Scatch

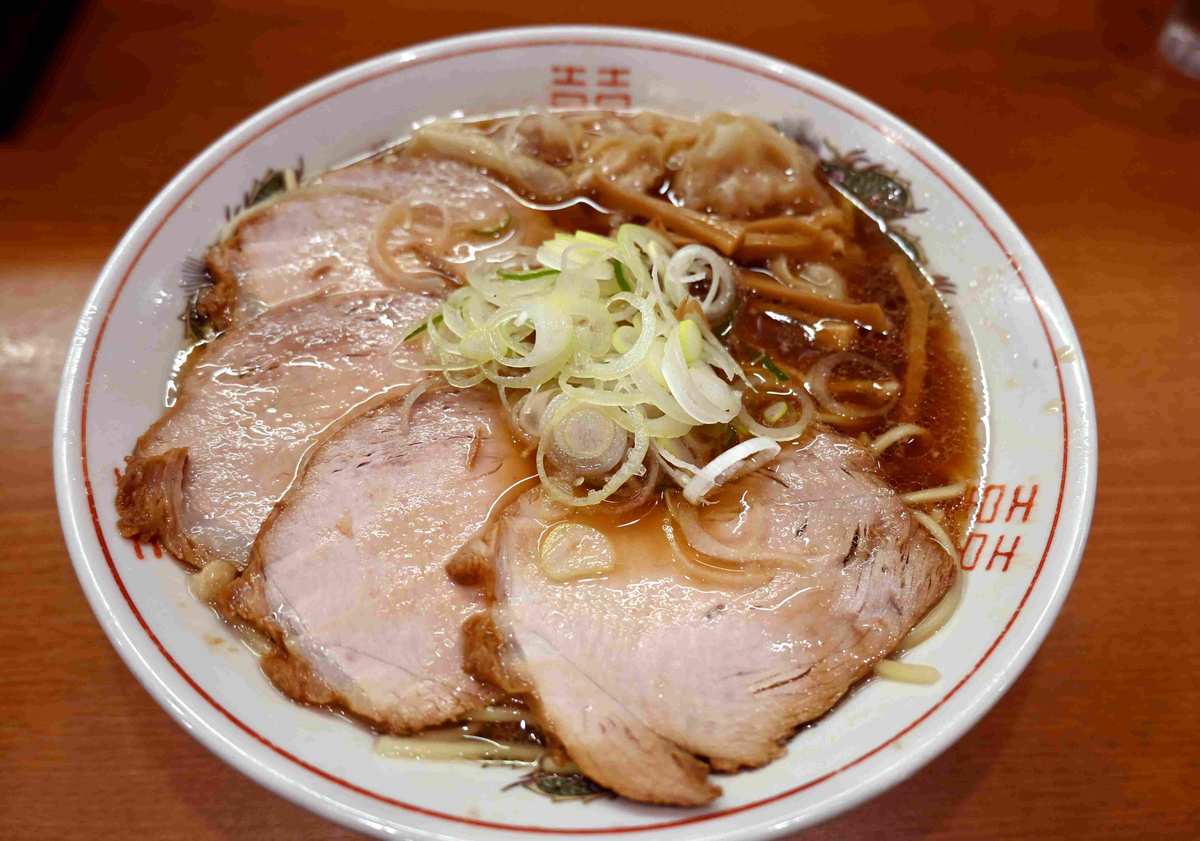

Noodles with pork chashu and wontons

15:46 JST, December 10, 2025

I set out for Tokyo’s Ginza to get a bowl of ramen and knew Kyoraku, approaching its 70th anniversary, would satisfy my purpose. The shop, founded in 1956, serves Japan’s most traditional and simple ramen: the chuka soba. It took a leap toward becoming an even more thriving establishment when third-generation owner Kazuhiko Nakano, 39, began serving noodles made from scratch. As I wandered through Ginza amid the year-end rush, I stopped by the shop, which always seems to have people lined up.

Ginza is a sophisticated district — you can feel it just by walking along its streets. The various Christmas illuminations added color to its twilight streets. The shop is about a 5-minute walk from JR Yurakucho Station. You can get there by walking along Ginza Marronnier Street, past the Ginza 2-chome intersection and further on. When I arrived, it was just before closing time at 5:30 p.m. and a few customers were still lined up outside. I had coffee at a nearby cafe, then returned and entered the shop.

“Welcome!”

I was greeted by the beaming smile of Kazuhiko’s 71-year-old mother, Kiyoko. The basis of the menu centers around their chuka soba noodles for ¥850. They serve other options with different toppings such as wonton or chashu. When I mentioned that I also wanted to try their homemade wontons and pork chashu, Kiyoko said, “Then pick this one,” pointing to the button for the noodles with chashu and wonton for ¥1350 on the ticket machine. I bought it.

The compact shop has eight counter seats and two tables. In the kitchen behind the counter, Kazuhiko began stuffing meat filling into wonton wrappers. Each one was meticulously handcrafted.

-

The noodles are made from scratch the night before and rest before being served.

-

The clear soy sauce broth

-

The wontons are all handmade.

-

Pork thigh chashu

Soon after, the chuka soba I was served at the counter was simple and beautiful. The clear soy sauce-based broth had the quintessential appearance of chuka soba, evoking the nostalgia of the Showa era, while the broth’s mouthfeel was mellow.

“The recipe is a company secret passed down from the founder, so I can’t share it,” Kazuhiko said apologetically. Even without knowing the recipe, the taste conveyed the craftsmanship.

What impressed me was the medium-thick noodles made from scratch. They glide smoothly into the mouth like soba noodles, with a softness that is just right, making them slippery and easy to eat.

Kazuhiko explained, “‘Udon is one shaku, soba is eight sun’ — you know that old saying, right? My noodles are eight sun — about 24 centimeters, the same as soba. That’s exactly the length of my outstretched palm.” It means that his noodles are shorter than typical ramen noodles and that’s why they’re easy to slurp. His noodles are also popular with foreign customers who find slurping noodles difficult.

The shop has short operating hours because Kazuhiko makes the noodles the night before at a separate location. He lets the noodles rest overnight before serving them.

-

Kazuhiko stuffs wontons with meat filling.

-

The freshly made noodles are ready to eat.

-

Dried menma before cooking

-

The same menma is seen after being cooked

The wrappers of the homemade wontons are smooth and delicious, and the chashu has a gentle flavor. The menma, also made from scratch, can be eaten with the noodles, offering a subtle, savory soy sauce taste. The menma takes about five days to complete and is made by rehydrating dried bamboo shoots in water before simmering and then seasoning them. When the menma absorbs water, it flattens and expands, so Kazuhiko cuts it thinly to make it easier to eat with the noodles. He showed me a large bag of dried bamboo shoots, saying, “I think it’s rare to see menma made from dried bamboo shoots like this.”

This well-balanced chuka soba offers a smooth, gentle flavor with a nostalgic touch. I found myself wishing I could be that cool guy who quickly eats this chuka soba in Ginza, saying little, and leaves.

3 generations dedicated to chuka soba

Third-generation owner Kazuhiko, left, and his mother Kiyoko

Kyoraku’s first-generation founder, Taichiro, started with a food stall and established the shop in Ginza 2-chome in 1956. That was the year the phrase “The postwar period is over,” written in the Economic White Paper, became a phrase heard everywhere. Taichiro passed away in 1999 at the age of 89 and the second-generation owner, Kikuo, 77, took over the business.

Kazuhiko, the third-generation owner, attended culinary school after graduating high school and worked at a Chinese restaurant. “I’ve loved eating since I was little,” Kazuhiko said. About five or six years into his job, Kikuo told him, “I’m getting tired and need you to help out at the shop.” Kikuo’s words came just as Kazuhiko was starting to enjoy his work, so after much deliberation, he decided to take over the shop.

After that, the building that housed the shop was slated for reconstruction, forcing the shop to close for 3½ years starting in 2016. During that time, Kazuhiko trained at a ramen shop, learning the skill to make his own noodles. When the shop reopened in the newly renovated building in 2019, he switched from using noodles sourced from a noodle factory to his own. This change earned him a reputation of serving “delicious” noodles.

-

The shops interior, with counter seats and two tables

-

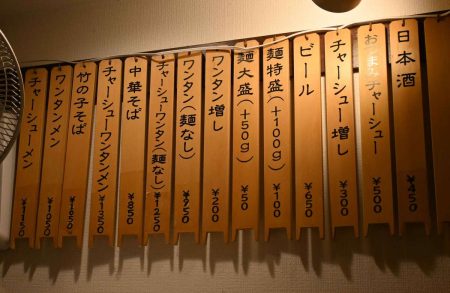

The ticket machine displays the menu

-

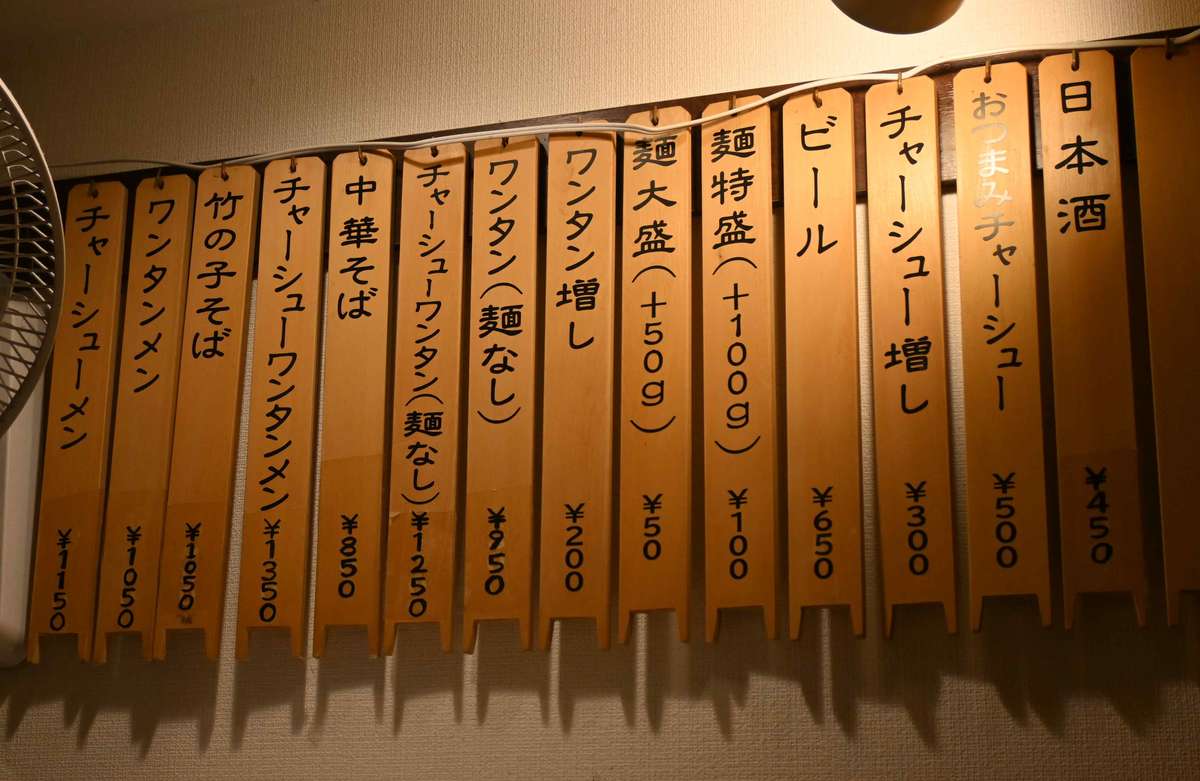

The traditional menu displayed on sticks of wood is seen on the wall.

-

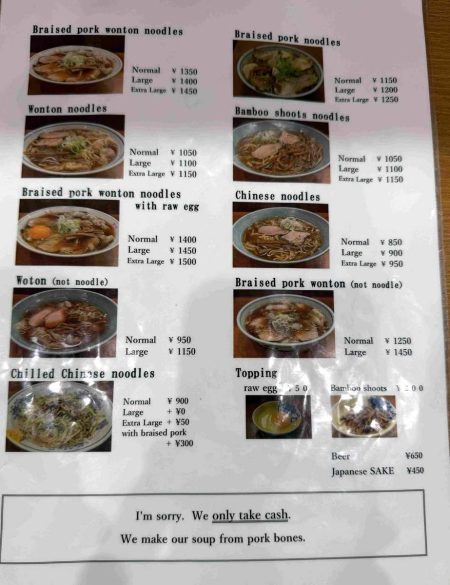

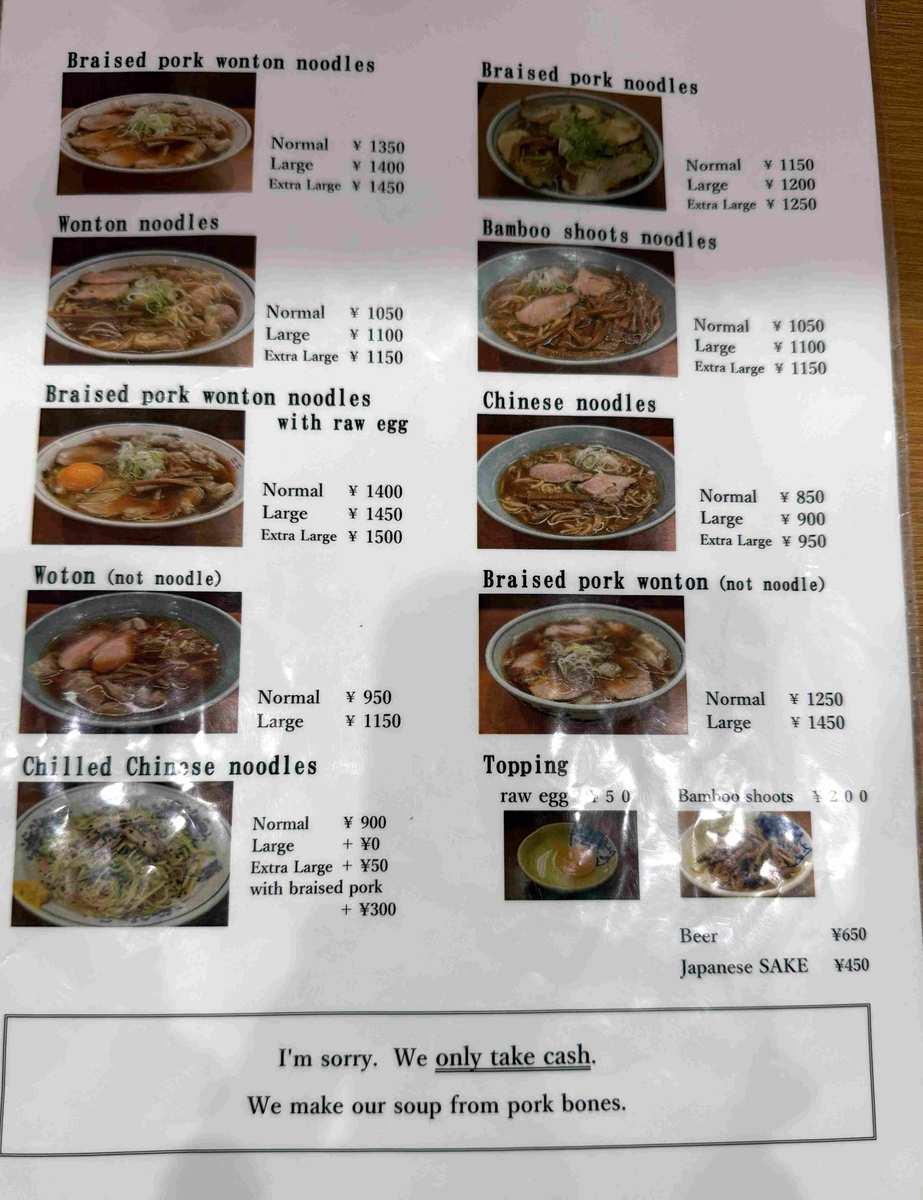

Kyoraku’s menu is seen with photos

-

Kyoraku’s menu is available in English with photos.

The shop, always bustling with regulars and foreign tourists, is now run primarily by Kazuhiko. He is supported by veteran staff, with Kikuo and Kiyoko also helping every day for short periods.

“I came here as a bride when I was 25, but we have regulars who’ve been coming longer than I have,” Kiyoko said. “The shop’s name embodies the founder’s spirit of ‘enjoying time together with our customers.’ Even as Ginza changes, we never forget our gratitude and want to keep enjoying long-lasting relationships with our customers.”

Regarding the shop approaching its 70th anniversary, Kazuhiko smiled shyly and said, “I just focus on doing the work in front of me diligently and steadily. I believe that’s how we’ll reach our 100th anniversary.”

Kyoraku

2-10-11 Ginza, Chuo Ward, Tokyo. Open from 11:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (until 4:00 p.m. on Saturdays). Closed Wednesdays, Sundays, and national holidays.

Futoshi Mori, Japan News Senior Writer

Food is a passion. It’s a serious battle for both the cook and the diner. There are many ramen restaurants in Japan that have a tremendous passion for ramen and I’d like to introduce to you some of these passionate establishments, making the best of my experience of enjoying cuisine from both Japan and around the world.

Japanese version

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan