Lifelike relief sculptures of cranes seem poised to step into the real world from a scene painted on a large Makuzu ware vase, dating from around 1876-82, that is now on display in the “East and West Rendezvous in Yokohama” exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of EurAsian Cultures.

13:14 JST, December 13, 2025

When Miyagawa Kozan was born in Kyoto in 1842, his family had been making pottery for generations. After taking over the business at the age of 19, he really shook things up.

The late 19th century was a good time for shaking things up. Long-isolated Japan was opening to the world, with novel and exciting goods and ideas flowing into and out of the country. Early in the Meiji era (1868-1912), Kozan relocated to the suddenly bustling international port of Yokohama, where he established a kiln to make ceramics for export. He specialized in large taka-ukibori high relief vessels from which lifelike painted sculptures of plants, birds and animals seem to leap out at the viewer.

His work was called Makuzu ware, named after his kiln, which in turn was named for the part of Kyoto he was from. Some of his works were displayed at the 1876 Philadelphia International Exposition, winning a bronze medal in the decorative arts category. About 50 items of Makuzu ware are on display right now at the Yokohama Museum of EurAsian Cultures in Naka Ward, Yokohama.

These exquisite works are part of an exhibition titled “East and West Rendezvous in Yokohama,” which runs through Jan. 12. The rest of the approximately 200 items on display include musical instruments, vintage photographs and hand-carved wooden furniture. Nearly all have characteristics reflecting the East-West cross-pollination of the time, and many also reflect the interplay of art and business.

A phoenix spreads its wings above branches of cherry blossoms atop an ornately carved wooden cabinet made in the period from around 1890 to 1920.

This is fitting, as the exhibition comes from the collection of Hiroshi Yamamoto, described in exhibition materials as “a Yokohama businessman who loves his hometown.”

His collection includes many pieces of Western-style wooden furniture embellished with three-dimensional carvings of plants and birds, such as a dark, thronelike chair with owls perched on its back that would fit in perfectly at Hogwarts. Often made by Buddhist temple sculptors who found themselves underemployed as Buddhism fell into official disfavor, such ornate furniture was intended mainly for the export market rather than for Japanese homes.

Going the other way, keyboard instruments first entered the Yokohama market as imports. For example, a piano dating from around 1890 was imported from Germany, but its wooden panels then had floral designs etched into them by a Japanese artisan. Nearby stands an organ built sometime around 1908-18 by a company founded by Torakichi Nishikawa, who learned enough about Western musical instruments to go into business making and selling them himself.

The letters N and S, bracketed by a pair of treble clefs, form the monogram of Nishikawa & Son. above the keyboard of an organ made by the firm in the period around 1908-18.

Similarly, photography was a new technology from abroad, but a genre of “Yokohama photographs” arose in which photos of Japanese life were painstakingly hand-colored and displayed in albums with elegant lacquerware covers. An English-language exhibition handout calls them both “souvenir art” and a “fusion of Western photographic techniques with traditional Japanese arts.”

The photos of Yokohama street scenes are fascinating windows into the past. One, taken sometime between 1880 and 1902, shows an expensive-looking two-story Western-style hotel with a Japanese tiled roof on one side of Kaigan-dori avenue and a vendor selling a sweet drink called ameyu from a tiny yatai stall on the other side. Curvy pine trees line the street, but so do arrow-straight telegraph poles. Rickshaw pullers pass ladies in long Victorian skirts while a large black dog squats nonchalantly in the middle of the road.

The museum’s vice director, Izumi Ito, pointed out one picture from the early 1870s as the oldest known photograph of Yokohama Chinatown. One clue to its age is the absence of gas lamps, which were installed in 1875.

Many street scenes show shops where wealthy Western visitors were invited to purchase Japanese items such as Makuzu ware. As an artist and a businessman, Kozan had a knack for creating beautiful items that those customers would want. When their tastes changed in the early 1880s, he shook things up yet again.

His tall ceramic vessels from before that time were elaborate and often whimsical. Life-sized statues of mice frolic around a miniature balcony encircling the neck of one large vase, while another vase has a large recess holding a diorama in which frogs perform acrobatics on a ladder. A relief sculpture of a bird on a third vase peers into a deep hole inside of which its chicks are squawking for their next meal — as if the vase itself were a hollow tree. The details are delightful.

A glistening crab appears to scurry along the edge of a Makuzu ware vase made in 1916.

But starting around 1882, Kozan turned from taka-ukibori to “underglaze” porcelain pieces with much simpler designs — often floral — that were painted onto sleeker vases and then glazed to a high shine. Following the market, Kozan learned these techniques from studying newly popular porcelain from Qing dynasty China. These pieces are as beautiful as his earlier ones, but they are elegant rather than entertaining.

The final section of the exhibition, titled “Makuzu Ware: Kaleidoscope,” shows other works by Kozan and his two generations of successors (also named Kozan). Many of them combine taka-ukibori whimsy and underglaze elegance. One large dark vase with a deep blue interior is perfectly smooth and unadorned, except for a petite crab poised on the rim, as if about to jump in. The glaze on the crab’s shell makes it look wet and alive. Another simple but humorous item is a glazed ashtray with a kingfisher perched on the rim. There is a single sculpted leaf on which one might rest a cigarette, and the bird is tilting its head as if interested in something under the leaf — a hidden fish?

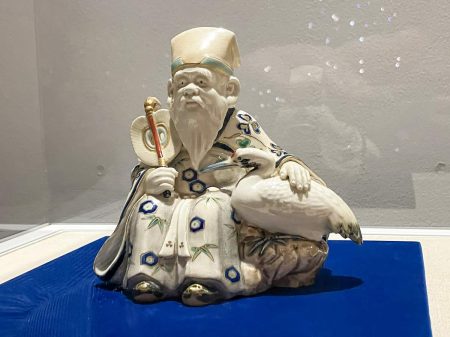

A Yokohama sugar importer commissioned this Makuzu ware portrait of himself in the style of a god of longevity sometime between 1897 and 1916.

There is also a figurine, made sometime between 1897 and 1916, in which several of the exhibition’s themes come together. It’s a white-bearded, friendly-looking old man in an elegant robe, sitting on a rock and contentedly petting a crane crouched under his arm. As with the animals in the taka-ukibori vases, his fairy-tale appearance compels the viewer to imagine stories about him. But the figurine’s simple color scheme and high shine also show the influence of the underglaze vases.

Finally, there is a business connection. The old man has two identities. One is Jurojin, a deity of longevity and one of the Seven Lucky Gods. The other is Kahei Masuda, a wealthy sugar importer. This Yokohama businessman was so enamored of Makuzu ware that he commissioned the figurine as a portrait of himself.

Related Tags

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan