Sayuki Kubo, left, and Masaki Kubo shave bamboo at their company’s workshop in Ikoma, Nara Prefecture.

13:21 JST, May 29, 2021

A variety of chasen whisks made by Masaki Kubo and other craftspeople at Chikumeido Sabun

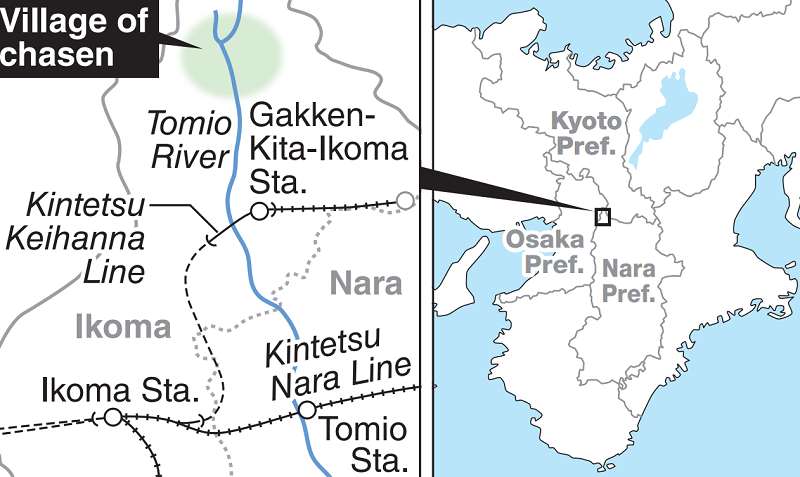

IKOMA, Nara — An essential tool for the traditional Japanese art of tea ceremony, a chasen bamboo whisk is used to foam the green tea in the tea bowl. The tool is said to have its origins in the Takayama district in Ikoma, Nara Prefecture, known as the “village of chasen.” The tea ceremony tool is carefully handcrafted with refined and seasoned skills.

The rhythmical sounds of craftspeople thinly shaving bamboo sheaths waft from a room in a tea ceremony tool maker’s workshop in Takayama. Masaki Kubo, 76, and his son, Sayuki Kubo, 47, are the 24th and the 25th owners of the company, Chikumeido Sabun.

“The most important step [in making chasen] is the process called ajikezuri,” the elder Kubo said. “It requires boiling the tips of the thin strings, or prongs, made from bamboo sheaths and shaving the chasen prongs so that they become thinner toward the tips. The process can affect the taste of the tea.”

The thinnest part after shaving is a staggering 0.03 millimeters.

“If we make a mistake, we’ll lose the [bamboo] prongs,” Kubo said with a chuckle.

The birth of a chasen tea whisk is believed to date back to the 15th century. Takayama Sosetsu, the second son of a lord of the Takayama Castle in Takayama, invented a chasen whisk per the request of Murata Juko, a friend of Sosetsu and the originator of wabicha simple-style tea ceremonies. He wanted a tool for mixing matcha green tea powder.

It is believed a descendant of Sosetsu subsequently passed on the tool to local retainers. Since then, production of whisks has continued in Takayama for about 500 years.

Hachiku bamboo, used to make whisks, is dried outdoors.

The bamboo used to make whisks is of the hachiku variety from the Kinki region.

At the company, making whisks starts with boiling about 13,000 stalks of hachiku bamboo, polishing them and then exposing them to the ultraviolet rays of the sun and cold winds for about a month during winter.

The craftspeople then cut the bamboo, about 2 to 2.5 centimeters in diameter, into 12-centimeter-long sections before peeling the thin outer skin from the bamboo. Next, 16 vertical cuts are made to each section while the bottom part is left alone. They then shave the inner side of the 16 parts and split each of them into 10 finer parts, making 160 prongs on each section. The prongs on the outer side are thicker while the ones on the inner side are thinner.

The next step is the process of ajikezuri. When the prongs are shaven to the right thickness, they are stroked by a paddle to make them curl toward the center. Then the prongs are bound at the base with a thread to support the bottom part.

The eight steps are divided among about 50 to 60 craftspeople at the company. Kubo gives a final look and examines the height of the prongs, the spacing between them, the overall shape and other aspects of each product and adds finishing touches.

Seeking to expand overseas

Tea whisks sold best during the 1970s, Kubo said.

“Tea ceremony was one of the things a woman was supposed to learn before getting married,” he said. “So young women flocked to the art. Such tradition is gone today.”

Alongside demand for such tools declining, imported ones from China and South Korea have become readily available.

To survive, Kubo cast his eyes overseas. He exhibited tea whisks from his company at an event in Paris in 2014 and another event in New York the following year. A matcha craze had taken root in both cities.

“It was a positive experience,” Kubo recalled.

The company has also developed thinner whisks that can be used to stir coffee and chocolate drinks. They also sell tea ceremony sets for outdoor use.

“We are now scattering various seeds,” Kubo said. “Tea ceremony is a culture that represents Japan, but it cannot survive if it stays the way it is. We must evolve it while treasuring the tradition.”

Kubo has his eyes set on the future.

The company produces about 120 different types of chasen whisks. Average ones cost from ¥2,500 to ¥4,500 each. High-grade ones made of susudake bamboo are available at about ¥20,000 each.

A map of Ikoma

Top Articles in Culture

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Chofu, Tokyo; Unique, Surreal Works Draw Steady Crowds

-

Japanese Film, Anymart, Wins Critics’ Award at International Film Festival in Berlin, Director’s Debut Feature Film Shocks Audiences

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan