Emperor’s Role in Japan-U.K. Ties / Japan Emperor Draws on Student Days at Oxford University; U.K. Experience Helped Shape Approach to Current Duties

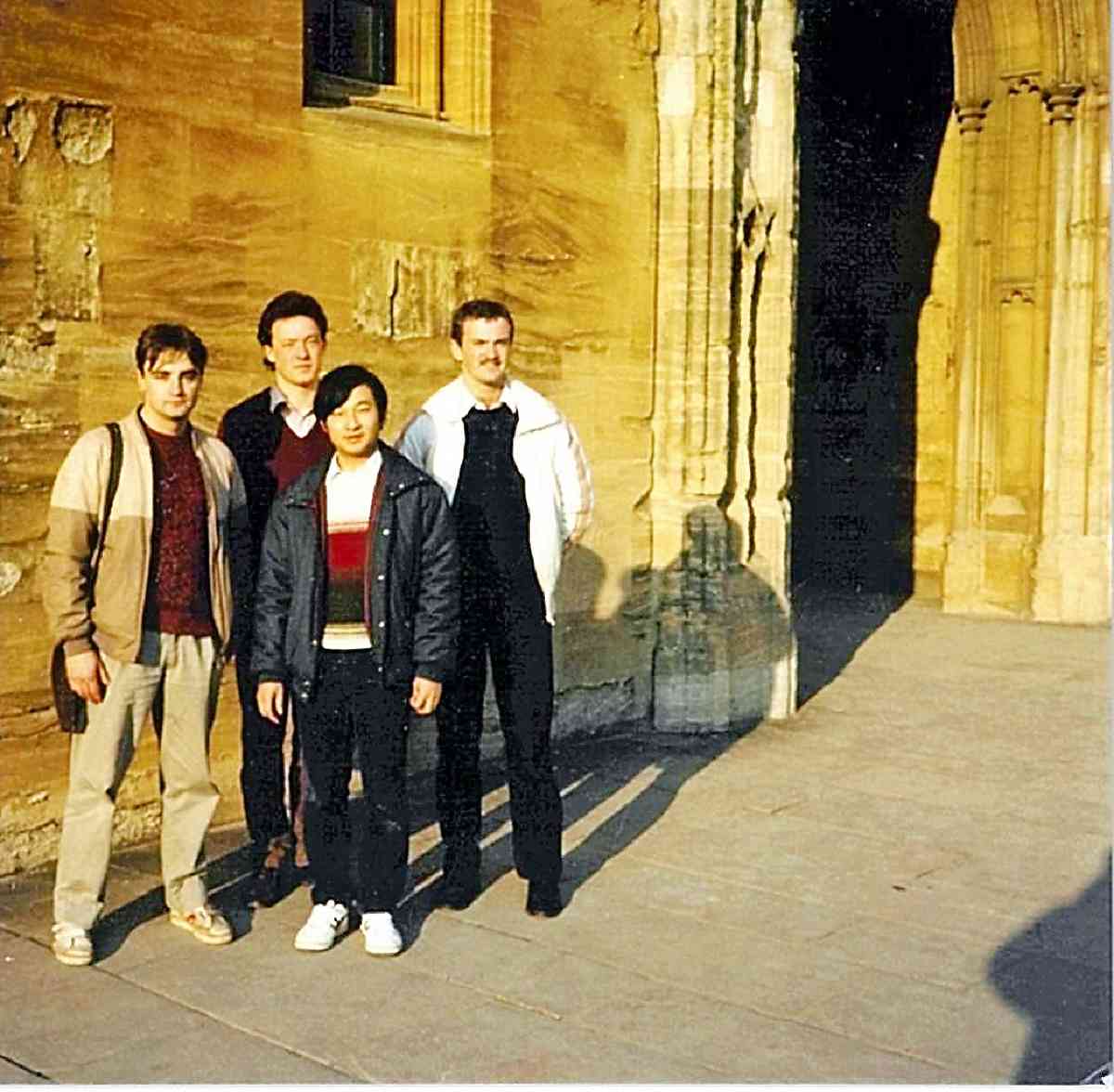

The Emperor, second from right, poses for a photo with Timon Screech, right, and other fellow students at Oxford University.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

6:30 JST, June 20, 2024

The Emperor studied at the University of Oxford in Britain from June 1983 to October 1985, living in a dormitory like an ordinary student and studying history, a subject in which he is interested.

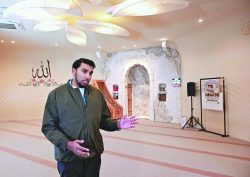

Prof. Timon Screech, 62, now with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, studied the Japanese language at Oxford. He became acquainted with the Emperor, who attended a lecture Screech was at, and invited him to dinner at his dormitory.

They ate a student meal on the floor below where teachers took their meals. During the dinner, the Emperor and Screech enjoyed chatting about things like their fellow students’ fields of study; tennis and music, which are the Emperor’s hobbies; and studying the Thames River.

On the following day, Screech received a letter. In elegant cursive, the letter expressed the Emperor’s thanks for the enjoyable dinner and conversation. At the bottom it said, “Regards Hiro.”

The Emperor was called Hiro during his time at the university, a nickname coined from his Imperial title of Hironomiya.

Looking at the letter now reminds Screech of an occasion when he couldn’t fully remember a waka poem he had studied. The Emperor smoothly recited the remaining part of the poem, which was written by priest-poet Saigyo Hoshi and is part of the Shin Kokin Wakashu collection.

Screech said, “It struck me that although Hiro fit in with students from all over the world, he was after all a special person who shouldered Japan’s traditional culture.”

According to Prof. Naotaka Kimizuka of Kanto Gakuin University, an expert in British politics and diplomacy: “Exchanges between the Imperial household and Britain’s royal family were initially just a tool for diplomacy and security. However, over the generations, that changed to a relationship in which they support and enhance while respecting each other’s traditional cultures.”

After the Emperor arrived in Britain, he stayed until the start of the university’s new term in the home of Tom Hall, a military attache to the British queen who ran a language school.

According to a former chamberlain of the late Queen Elizabeth II, Hall was a member of the inner circle, the close aides to the queen. In keeping with her wishes, Hall provided opportunities for the Emperor to study English and supported him so that his life in Britain would be smooth.

The British government also provided careful support for the Emperor’s student life. Then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher invited the Emperor to her official villa and they had lunch together.

She also arranged for him to visit the British foreign ministry, and then Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe served as his guide.

Secret service guards were appointed to safeguard the Emperor while he stayed in Britain. According to a former close aide of the Emperor, the British government initially was reluctant to do so, as it did not usually provide guards for students from any countries’ royal families.

However, then Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone strongly requested the Emperor be protected, so Scotland Yard dispatched two officers for the duty.

The National Archives of Britain contains a record of Thatcher saying: “His Imperial Highness benefited both from his academic studies and from his personal contacts and experiences in the United Kingdom … his stay with us has highlighted the close and friendly relations between our two countries.”

Queen Elizabeth visited Japan in 1975, the first U.K. monarch to do so. She spent time with Emperor Showa, who welcomed her as a state guest.

The queen is said to have expressed her thanks to Emperor Showa, saying that as queen, she was alone and the only person who must make important decisions. Emperor Showa, having been on the throne for 50 years at that time, was the only person who could understand the queen’s situation, the British monarch described, adding that she had traveled to Japan, halfway around the world, to receive his wisdom and that she had been amply rewarded.

Japan’s emperors and Britain’s monarchs are in a special position, inheriting their special status from birth. They have conflicted feelings that members of the public can never know.

When the Emperor made a short trip with fellow students at Oxford, they were hit by a sudden downpour. They stood still without umbrellas, and a car of secret service guards approached. The guards told the Emperor to get in, as they feared he might catch a cold.

The Emperor knocked on the hood of the car with a regretful expression and got in. His fellow students later speculated that he had probably enjoyed getting wet in the rain with his friends.

The Emperor published a memoir in 1993, “Temuzu to Tomoni” (The Thames and I: A Memoir of Two Years at Oxford), in which he remembered that time as the most enjoyable period in his life.

In February 2020, the year after his enthronement, he held a press conference for the first time as Emperor. Describing his years in Britain, the Emperor said: “I was able to conduct myself freely. I interacted with diverse people, and was able to see the U.K. society from the inside … hone a perspective for viewing Japan more objectively from the outside,” adding that “I was able to gain numerous valuable experiences that have considerably influenced how I engage in my current official duties.”

Related Articles

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Japan Govt Aims for 10-Fold Increase in Computing Power of Superc...

-

Kesennuma, Miyagi Pref., Locals Raise Carp Streamers as Symbol of...

-

Iran Situation: Significance of Rule of Law Must Be Conveyed

-

Trump Says Iran Had a New Site for Developing Nuclear Weapons

-

Toyota Advancing Plant-Based Biofuel Development in Fukushima Tow...

-

2 People Reportedly Found on Mt. Fuji; Hiking Trail Currently Clo...

-

Japan's TEPCO to Raise Electricity Rates for Corporations in Apri...

-

Rapeseed Flowers Reach Peak Viewing Period at Tokyo's Showa Kinen...

Popular articles in the past week

-

Ibaraki Pref.'s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

-

Amid Strait of Hormuz Blockade, Shipping Companies Scramble to Ge...

-

Govt to Utilize ODA for Ensuring Economic Security; Securing Ener...

-

Japan Govt Survey Finds Just 10% of Workers Want Working Hours to...

-

Japan's 2nd Round of U.S. Investments May Be Worth Over $100 Bill...

-

Imperial Family Watches World Baseball Classic Game Against Austr...

-

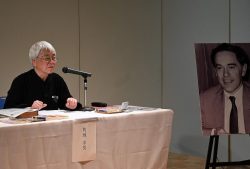

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays T...

-

Nippon Life Insurance's U.S. Arm Sues OpenAI Over Legal Assistanc...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanes...

-

Japan's Govt to Submit Road Map for Growth Strategy in March, PM ...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

-

Ibaraki Pref.’s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed