Noto Peninsula Quake Victims Seek Places To Store Home Goods; Many Forced To Throw Items Away Due To Lack Of Space

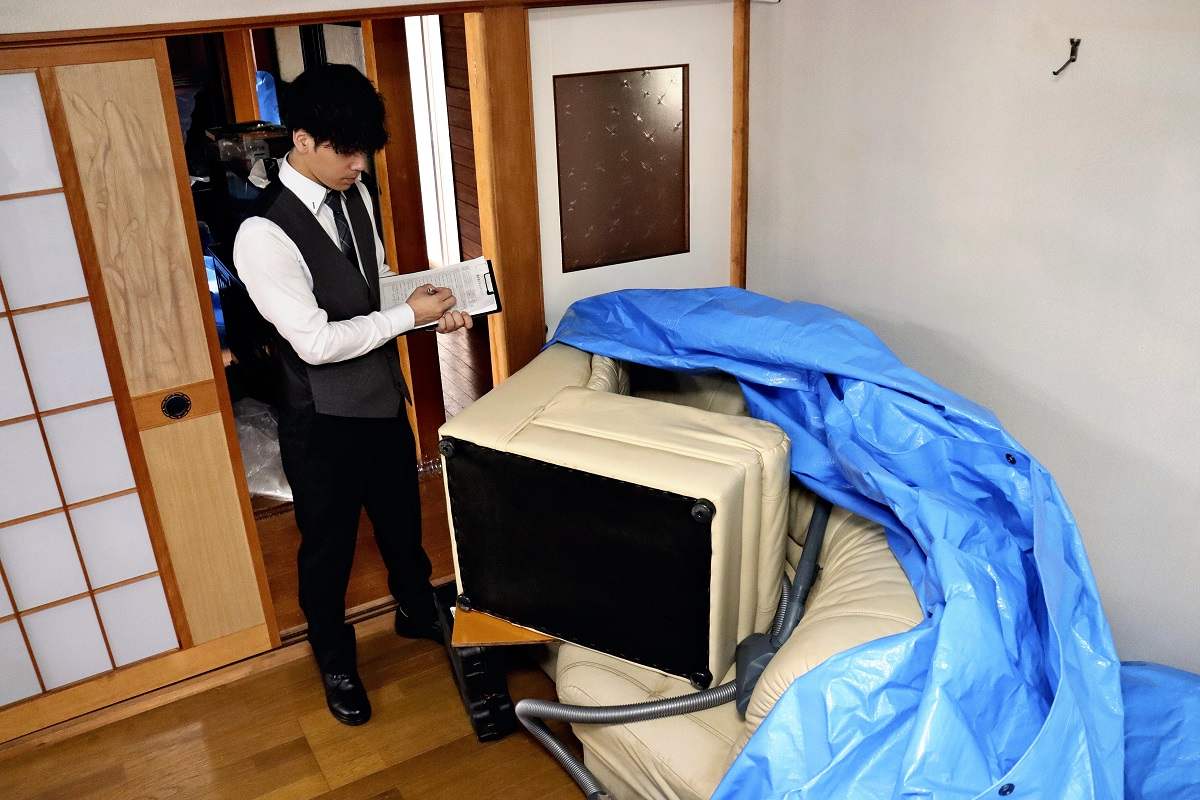

An official of a storage service provider examines household goods at a quake-hit house in Suzu, Ishikawa Prefecture, on June 18.

11:30 JST, August 22, 2024

People whose houses were partially or totally destroyed by the major earthquake that hit the Noto Peninsula on New Year’s Day are concerned about where to keep their household goods until the publicly funded demolition of their homes.

Temporary housing provides only limited storage space, but the cost of private storage services puts a serious financial burden on quake-affected people, some of whom have been forced to dispose of household items, such as Buddhist altars. Experts point out the need for public support, including financial assistance, saying, “disaster victims will feel a great sense of loss if they have to give up their household goods.”

At a house in Suzu, Ishikawa Prefecture, Akihiro Hamashima, a 40-year-old office worker from Nonoichi in the prefecture, asked a storage service provider to estimate the cost of temporary storage of household goods. The house, where his parents used to live, was partially destroyed in the earthquake, and the couple applied to have the house demolished with public funds. They now live in an apartment outside the prefecture, but the place is too small to store the household goods they own.

The storage fee for eight items, including a refrigerator, a sofa and a massage chair that was a gift from the four siblings for their parents’ 60th birthday, turned out to exceed ¥100,000 for the first month, including transportation costs, and about ¥14,000 per month after that. The date when the house will be demolished has yet to be decided. “It’s difficult to keep them anywhere else. I’ll decide after consulting with other family members,” Hamashima said.

Space is also limited at temporary housing. A priest from Suzu said some people have decided to dispose of their Buddhist altars. “People are being forced to make tough decisions,” he said.

Being aware of such voices, the prefectural government has posted a list of companies that offer paid storage services on its website. There have been inquiries about storage for chests of drawers, Buddhist altars and Wajima lacquerware among other items, but few cases result in contracts, according to officials.z

Many warehouses are located in Kanazawa, resulting in higher fees due to costs for transportation and labor to provide security against theft. If a Buddhist altar and a sideboard are transported from Wajima, the annual storage fee at a Kanazawa-based company will be ¥250,000, including transportation costs.

Meanwhile, the Anamizu town government began subsidizing storage costs, capped at ¥50,000 per household, in June. In 2007, when a major earthquake hit the Noto Peninsula, the town accepted household items and temporarily stored them in the gymnasium of an elementary school. This time, however, the damage was too great to make enough space available. “We’ve received many inquiries about where to store items, and we hope to meet the residents’ needs,” said an official of the town’s environment and safety division. The town expects that 100 households will use the subsidies.

“Household goods are not only important for the reconstruction of the victims’ future lives but also as a source of emotional support for the people who have kept them for many years,” said Ryosuke Aota, a professor of disaster relief policy at the University of Hyogo.

“Local authorities should also consider providing financial assistance by making use of the prefecture’s reconstruction fund, which can be used flexibly,” the professor said. “An effective approach might be to manage storage facilities in a flexible manner by leaving their management to local communities and supporters.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan