Looking at Ukraine, Former Residents of Japan’s Northern Territories See Parallels in Russia’s Aggression

Kunashiri Island is seen in the distance beyond Cape Shiretoko in Hokkaido, as viewed from a Yomiuri Shimbun helicopter.

6:00 JST, September 18, 2025

Even after Japan surrendered in the final days of World War II, the Soviet Army continued to invade Japanese territory. The islands now known as the northern territories, where about 17,000 Japanese lived, were occupied by the Soviet Army by mid-September in 1945.

In light of Russia’s continuing aggression against Ukraine, former residents of the islands feel rekindled longing for their lost hometowns, remembering that the tragic situations of war have not disappeared from the world.

Tae Sasaki talks about her memories of Kunashiri Island in Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo, on Aug. 21.

Prosperous islands

Tae Sasaki, 88, a former resident of Kunashiri Island in the northern territories who now lives in Sapporo, said she thinks of the island as her homeland, as she was born and raised there.

In her childhood, she played in the sea in summer and enjoyed seeing drift ice in winter. There was a hot spring on the island and residents caught crabs and gathered funori seaweed on the shore. The island was rich in such natural resources.

There was also a sad memory for her. When Sasaki was 4, her father died when a fishing boat capsized. Many people gathered on a beach where the body of her father was found.

Her father’s body was cremated on a nearby hill, and her mother raised Sasaki and her two younger sisters totally on her own.

On one night in mid-July in 1945, a city on the opposite side of the strait was engulfed in flames. It was a bombing raid on Nemuro, Hokkaido, in which about 400 people were killed. Later, Sasaki learned that her aunt was among the victims.

Also in Kunashiri Island, air raid warnings were issued increasingly often, and Sasaki evacuated onto a mountain behind her house each time.

Despite the situation, adults around her said that divine winds would blow and Japan would win the war.

But a year and a half later, Kunashiri Island was occupied by the Soviet Army and Sasaki saw armed Soviet soldiers walking around freely on the island.

Other residents in her neighborhood escaped from the island one after another. Sasaki’s family also finally decided to flee.

Sea of fears

One night in late September 1945, Sasaki, who was then 8, stood on a beach of the island. The blue sea, which was familiar to her, now looked black and was heaving weirdly.

Aiming to reach Nemuro, 60 kilometers away, a total of eight family members, including Sasaki and her grandparents, mother and sisters, boarded a small boat.

They met with a fishing boat off the shore and a ladder was hung down from it. Sasaki began to climb up the ladder, but the small boat plunged up and down on the waves.

Sasaki was very scared thinking, “I may fall into the sea.” Somebody grabbed her hand and pulled her onto the fishing boat. Sasaki barely made it aboard.

Due to fear and fatigue, Sasaki fell asleep. Then she woke up hearing conversations of adults around her. One of them said, “I evaded a Soviet patrol ship.”

When the day dawned, Sasaki could see Nemuro Port. Eight hours had passed since she and her relatives had left Kunashiri Island.

Sasaki was relieved and thought: “There are many Japanese here. I can survive.”

Physically close, psychologically far

Mountains of debris were seen in Nemuro, as 80% of the city’s urban area had been burned down in air raids.

The eight members of Sasaki’s family made their way toward Kushiro, Hokkaido, to seek help from an acquaintance. During the trip, they spent nights in many places such as a shed and a barn.

Temperatures fell to minus 30 C in winter in the northern region. Snow stuck to their futon blankets and sometimes even their clothes were frozen.

Sasaki once ate a discarded potato she had found, and it tasted very bitter. In the war, a younger brother of Sasaki’s mother, who was drafted into the military, died on a battlefield. Sasaki’s grandmother, traumatized by losing her son in the war, suffered a mental illness and threw herself into a river.

Sasaki resettled in Nemuro while in the sixth grade of elementary school and became a bank employee at 18. Then she married and had two daughters.

Sasaki remembers a time when she was 37 and her family was enjoying a drive in eastern Hokkaido when the mountains of Kunashiri Island came into view.

At the time, Sasaki thought, “My homeland is so beautiful and surprisingly close to me.”

‘Free visit’

Sasaki joined people demanding the return of the four islands of the northern territories. In 2014 and 2016, she revisited Kunashiri Island for the first time in about 70 years as a member of groups who were permitted to do so to visit relatives’ graves or make “free visits” based on an agreement between the Japanese and Russian governments.

Though Sasaki stood on the beach from which she escaped from the island, the townscapes that had existed in those years was gone. Because there was a risk of landslides on a road to her former house, she had to turn back halfway.

Despite the changes, Sasaki spotted a pile of shells at a site where a scallop-processing facility once stood, while she was returning. She could not help but dab her eyes, fighting back tears as she thought, “Japanese used to live here.”

She placed a photo of herself and her family members on a beach of the island where her father’s final resting place and offered a prayer to him.

In Sasaki’s eyes, the aggression by Russia against Ukraine, which started in February 2022, overlaps with the northern territories issue. In September 2022, Russia announced it was annulling the agreement on free visits and other visits by former residents of the northern territories.

Sasaki has served as a storyteller about northern territories affairs. She believes that her father’s soul still resides on Kunashiri Island. She can also understand the regret her grandparents and mother felt after they had to flee from the island.

As a former islander, Sasaki wants to convey a message: “I want to freely offer my prayer to the souls of the deceased, and I also hope peace will arrive in Ukraine as soon as possible, even if just one day earlier.”

History of northern territories

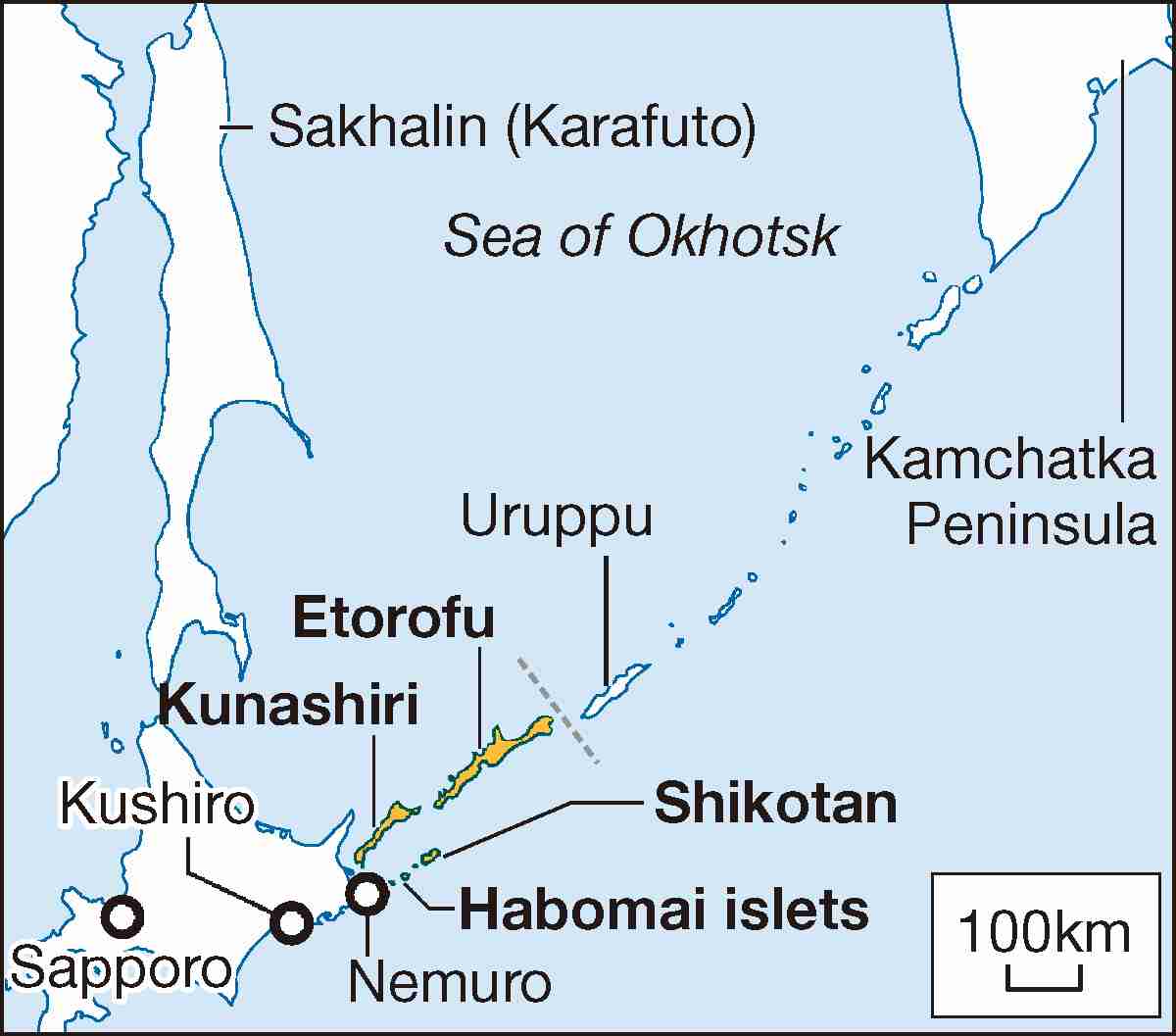

The northern territories comprise Etorofu Island, Kunashiri Island, Shikotan Island and the Habomai group of islets. Their total land area is almost equivalent to that of Chiba Prefecture.

In 1855, the shogunate government of Japan and the Russian Empire signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, between Japan and Russia, drawing a national border between Etorofu Island of Japan and Uruppu Island of Russia.

But the four northern territories islands, on Japan’s side of that line, were attacked and occupied by the Soviet Army just after the end of World War II.

According to the Sapporo-based League of Residents of Chishima and Habomai Islands, the number of former islanders as of the end of July was 4,897, and their average age reached 89.6 years old.

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Girls Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan