Takatoshi Suzuki supports his family by running fishing cruises. “I hope I can use my years of experience as a fisherman to make customers happy,” he said on Feb. 28 in Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture.

10:22 JST, March 24, 2021

This is the fifth and final installment of a series in which Yomiuri Shimbun reporters share an intimate look at families who were directly affected by the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami.

※※※

ONAGAWA, Miyagi — It is just after 5 a.m. Having washed some rice, Takatoshi Suzuki, a 54-year-old native of Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, turns on the rice cooker and says a short prayer in front of the Buddhist altar before quietly leaving his house. He gets in his truck and drives to the port on this clear day in late February.

Right-eye flounder is in season now. In early summer it will be olive flounder and cod. A fisherman by trade, Takatoshi has been running cruises for the last few years, guiding customers to the best fishing spots. He can see the satisfaction of a big catch on the faces of his customers.

“Please come again,” he tells them.

In March 2013, two years after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I heard about someone living in a temporary housing complex who planned to resume fishing for Japanese sand lance, a famous springtime delicacy.

I found him clumsily folding laundry in a tiny temporary housing unit, while his daughter Yuzuha, who was 4 at the time, climbed all over him seeking attention. “I can’t keep up with it all,” he said.

In August 2013 the Suzuki family moved from a tiny, one-room temporary housing unit to another unit.

The tsunami had taken his wife, Tomoko, and he had been feeding and caring for his three children all on his own since then. Takatoshi could not hide his exhaustion.

Yet when I asked him about fishing, his words suddenly gained force. “Once the New Year comes, I get excited. I’ll never forget the joy of catching a fish. It keeps me fishing,” he said.

The next spring, in 2014, I accompanied him fishing for Japanese sand lance. We left the port while it was still dark on his 8-ton fishing boat, the Kanemiya Maru. It took about three hours to reach the fishing grounds.

Japanese sand lance are caught with “scoop nets.” When seagulls or fur seals are spotted chasing sand lance near the surface of the sea, the engine is put to full throttle to scoop up the school with the net.

Good eyes and plenty of experience are key to a successful catch. Takatoshi stared at the sea and sky like he was challenging them, which made me hesitant to approach him.

When we returned to port, he told me: “The sea is what I really need to survive here. Tsunami are scary, and in a storm you get tossed about like leaves on a tree. Even so, I could never hate it.”

But the fish are no longer there to be caught. According to the Miyagi prefectural government and other sources, the Japanese sand lance catch the last few years has been a tenth or less of what it was before the earthquake. Some think the sandy areas where the fish hatch were disturbed by the tsunami. Global warming is also seen as a factor.

Oyster farming, another source of income, has seen orders plunge due to the coronavirus pandemic. So now Takatoshi is putting his fishing nets aside and pinning his hopes on the fishing cruises.

Photo of mother

“I’d forgotten about these pictures,” said Tomohiro, the family’s 21-year-old son, while looking at a photo album in the attic of their home. The album had been saved from their previous house, which was swept away by the tsunami.

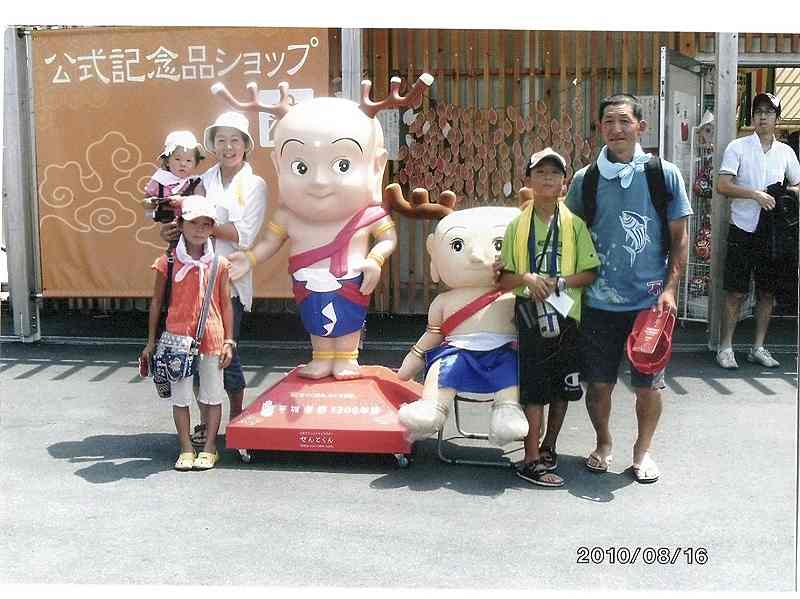

The photo is dated Aug. 16, 2010. In it, Tomoko smiles as she holds Yuzuha. The older sister, Nao, who was an elementary school student then and is 19 years old now, and Takatoshi are there too. This is the last photo of the five of them together, taken on a trip to Nara Prefecture the year before the earthquake.

The last photo with the whole family together was taken in Nara Prefecture, where Tomoko was raised, in August 2010.

There is also a photo of Tomoko holding Tomohiro as a baby. “She really loved us, didn’t she,” Tomohiro said.

He used the photo as his profile picture on Instagram.

“Time has stopped for the last 10 years,” Takatoshi said. He does not think the feelings of loss and sadness will fade. “I’m always being reminded that my family isn’t together,” he said. He hasn’t used a camera much since the earthquake.

But his children have grown up. Next spring, Tomohiro will graduate from university and Nao from junior college. Yuzuha, now 12, is starting junior high school this spring. She loves Korean boy bands and is studying Korean.

Happily, the fishing cruise business has created a virtuous circle in which customers tell other people about the experience, who then become customers themselves, enabling Takatoshi to support the family. After all, there is no option but to live by the sea.

The Suzuki family — from left Tomohiro, Yuzuha, Takatoshi and Nao — walks in central Onagawa.

“I have to keep at it for another 10 years,” he said. This thought keeps Takatoshi going.

Suzuki family profile:

Takatoshi Suzuki, a fisherman in Onagawa, Miyagi Prefecture, lost his wife Tomoko, then 38; his father Kanetoshi, then 79; and his mother Ritsuko, then 79, in the tsunami. He now lives in a home built on higher ground with his son Tomohiro and second-oldest daughter Yuzuha. His oldest daughter Nao lives in Sendai.

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan