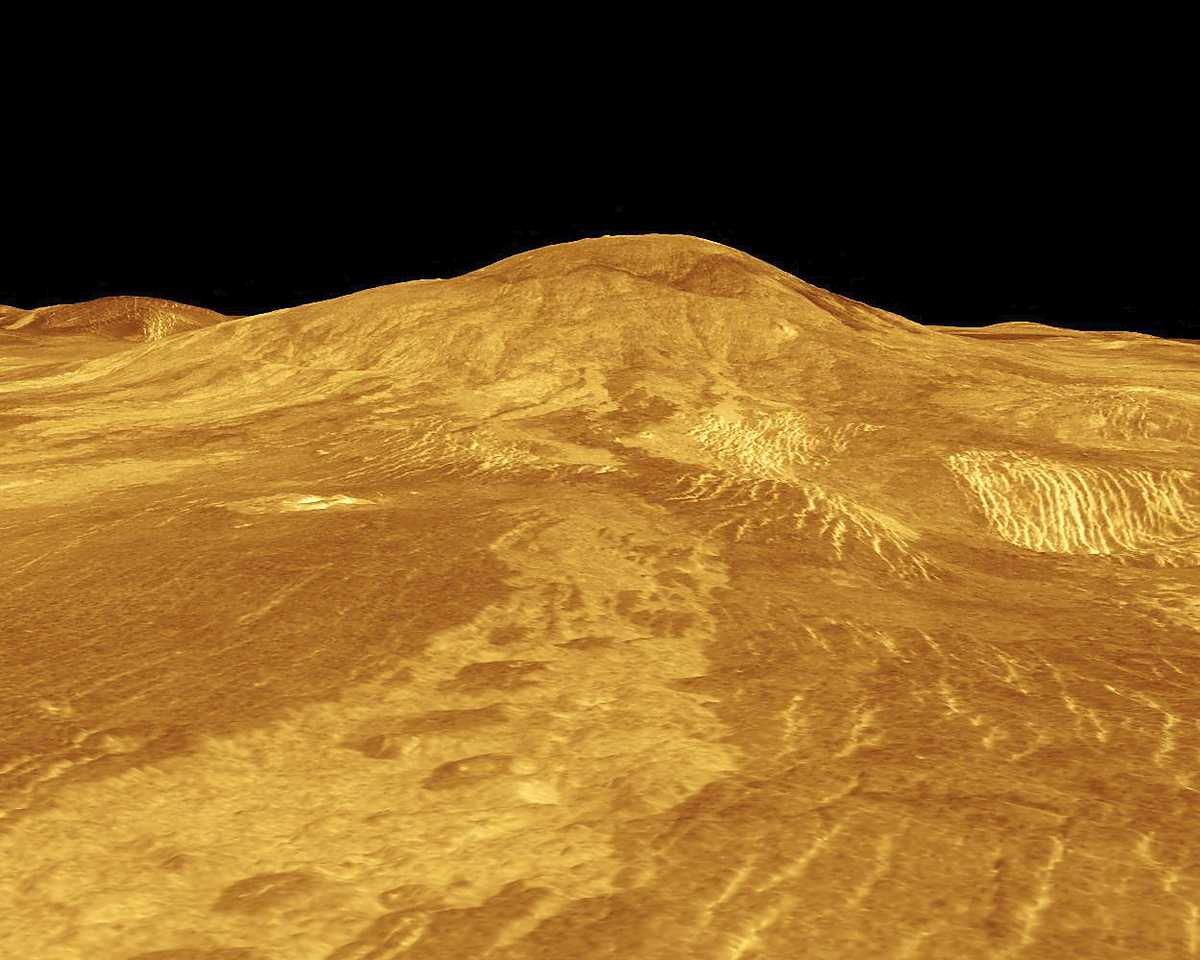

The volcano Sif Mons, which is exhibiting signs of ongoing activity, is seen in this undated image of a computer-generated 3D model of Venus’ surface.

16:26 JST, December 26, 2024

WASHINGTON (Reuters) — Earth is an ocean world, with water covering about 71% of its surface. Venus, our closest planetary neighbor, is sometimes called Earth’s twin based on their similar size and rocky composition. While its surface is baked and barren today, might Venus once also have been covered by oceans?

The answer is no, according to new research that inferred the water content of the planet’s interior — a key indicator for whether or not Venus once had oceans — based on the chemical composition of its atmosphere. The researchers concluded that the planet currently has a substantially dry interior that is consistent with the idea that Venus was left desiccated after the epoch early in its history when its surface was comprised of molten rock — magma — and thereafter has had a parched surface.

Water is considered an indispensable ingredient for life, so the study’s conclusions suggest Venus was never habitable. The findings offer no support for a previous hypothesis that Venus may have a reservoir of water beneath its surface, a vestige of a lost ocean.

Volcanism, by injecting gases into a planet’s atmosphere, provides clues about the interior of rocky planets. As magma ascends from an intermediate planetary layer called the mantle to the surface, it unleashes gases from deeper parts of the interior.

Volcanic gases on Earth are more than 60% water vapor, evidence of a water-rich interior. The researchers calculated that gases in Venusian eruptions are no more than 6% water vapor, indicative of a desiccated interior.

“We suggest that a habitable past would be associated with Venus’ present interior being water-rich, and a dry past with Venus’ present interior being dry,” said Tereza Constantinou, a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy and lead author of the study published on Dec. 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“The atmospheric chemistry suggests that volcanic eruptions on Venus release very little water, implying that the planet’s interior — the source of volcanism — is equally dry. This is consistent with Venus having had a long-lasting dry surface and never having been habitable,” Constantinou added.

Venus is the second planet from the sun, and Earth the third.

“Two very different histories of water on Venus have been proposed: one where Venus had a temperate climate for billions of years, with surface liquid water, and the other where a hot early Venus was never able to condense surface liquid water,” Constantinou said.

The Venusian diameter of about 12,000 kilometers is just a tad smaller than Earth’s 12,750 kilometers.

“Venus and Earth are often called sister planets because of their similarities in mass, radius, density and distance from the sun. However, their evolutionary paths diverged dramatically,” Constantinou said.

“Venus now has surface conditions that are extreme compared to Earth, with an atmospheric pressure 90 times greater, surface temperatures soaring to around 465 C, and a toxic atmosphere with sulfuric acid clouds. These stark contrasts underscore the unique challenges of understanding Venus as more than just Earth’s counterpart,” Constantinou said.

The story appears to have been different on Mars, the fourth planet from the sun.

Surface features on Mars indicate it had an ocean of liquid water billions of years ago. No such features have been detected on Venus. Mars, according to research published in August based on seismic data obtained by NASA’s robotic InSight lander, may harbor a large reservoir of liquid water deep under its surface within fractured igneous rocks, holding enough to fill an ocean that would cover its entire surface.

While Venus has been studied less than Mars, new explorations are planned. NASA’s planned DAVINCI mission will examine Venus during the 2030s from its clouds down to its surface using both flybys and a descent probe. Also during the 2030s, the European Space Agency’s EnVision orbital mission is due to conduct radar mapping and atmospheric studies.

“Venus provides a natural laboratory for studying how habitability — or the lack of it — evolves,” Constantinou said.

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

-

iPS Cell Products for Parkinson’s, Heart Disease OK’d for Commercialization by Japan Health Ministry Panel

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan