Fires in Brazilian Amazon Peak in September, Yomiuri Shimbun Analysis Shows, Due to Suspected Pre-Rainy Season Logging

Felled trees burn in the Amazon

6:00 JST, November 4, 2025

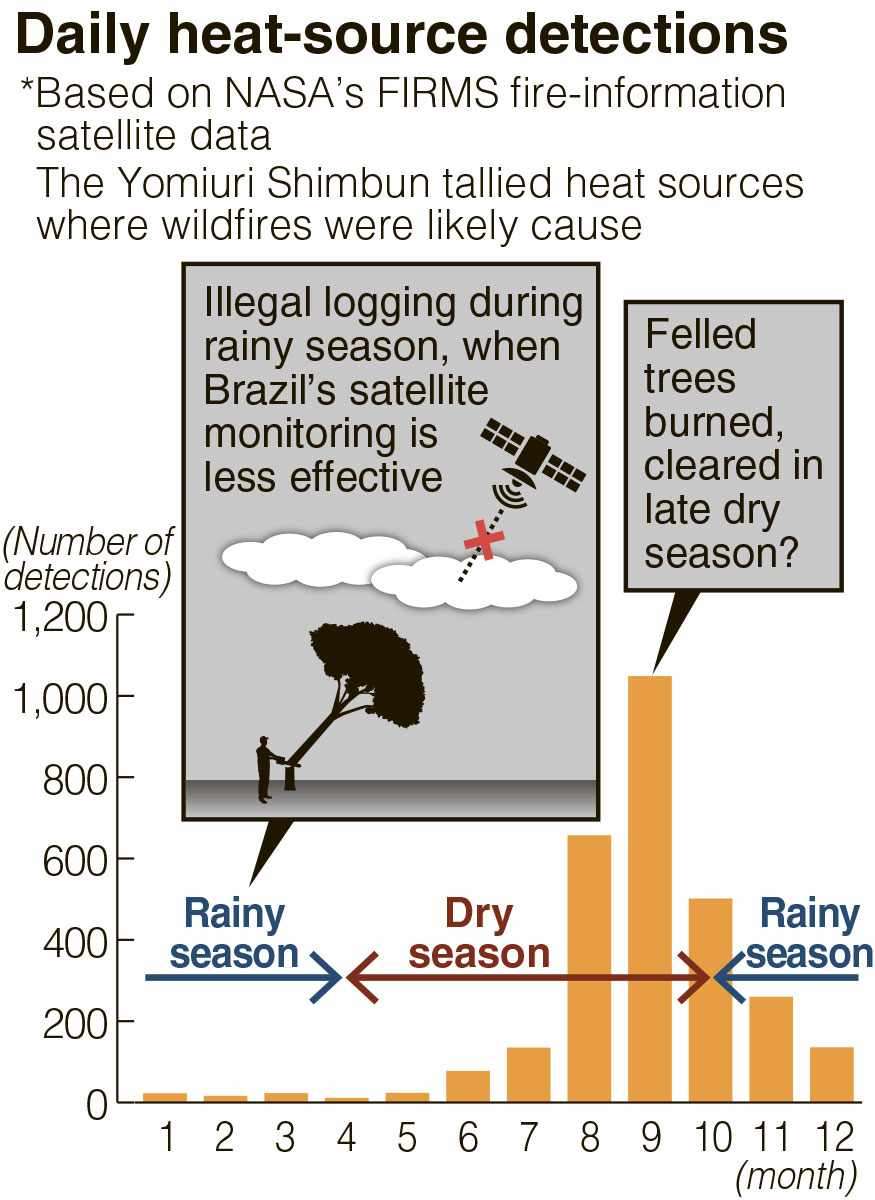

Fires in the Brazilian portion of the Amazon rainforest surge each year in September, the tail end of the dry season, a Yomiuri Shimbun analysis of satellite data has found. On the ground, illegal logging to open up more land for agricultural use is rampant, and there are indications that felled trees are being burned at the most combustible time of year.

The Amazon, often called “the planet’s lungs,” absorbs vast amounts of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, and is expected to be a key focus of conservation discussions at the 30th Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP30), which will begin Monday in Brazil.

Stretching across nine South American countries and territories, the Amazon covers more than 6 million square kilometers — about 15 times the land area of Japan — with roughly 60% in northern Brazil. Illegal practices are widespread, including the clearing of land without permits to create more cropland and pasture. According to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, about 400,000 square kilometers of forest have been lost in Brazil alone over 30 years from 1990.

The Yomiuri Shimbun analyzed publicly available data from NASA satellites that detect heat sources. Excluding volcanoes and industrial zones, the paper tallied the number of likely wildfire detections (each representing 1 square kilometer) recorded in the Brazilian Amazon since 2000.

The month with the highest average number of daily wildfire detections was September, at 1,048, nearly 100 times the April low of 11. Daily detections peaked at 2,396 in September 2007 and have trended downward since 2008. However, roughly 1,000 heat sources per day are still detected.

In the Amazon, the dry season lasts through around September, and rainfall increases from about October as the rainy season begins.

Brazil’s government primarily relies on imagery from its own satellites to monitor illegal logging. However, cameras on optical satellites cannot capture images when the sky is not clear. During the rainy season — when cloud cover is heavy — monitoring becomes less effective, and logging may proliferate. To strengthen oversight, Brazilian authorities are also using data from Japanese satellites that use other imaging techniques to observe the ground regardless of weather conditions.

Yasumasa Hirata, a senior researcher at Japan’s Forest Research and Management Organization and expert on the Amazon, notes, “After logging, timber that cannot be sold is left to dry sufficiently until September and then burned.” He attributes the decline in deforestation partly to voluntary measures by companies, such as bans on purchases of soy grown on illegally cleared land, which have “slowed [the practice] to a certain extent.”

At the current pace of deforestation, however, some projections indicate that, combined with damage from global warming, the rainforest could become irrecoverable within this century. Deforestation also harms ecosystems.

The World Meteorological Organization reported that concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide hit a fresh record last year, with Amazon fires cited as one contributing factor. Tokuta Yokohata, principal researcher at Japan’s National Institute for Environmental Studies, warns: “Conditions in the Amazon affect the climate even in far-off Japan. The world should act together to implement countermeasures.”

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

-

iPS Cell Products for Parkinson’s, Heart Disease OK’d for Commercialization by Japan Health Ministry Panel

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan