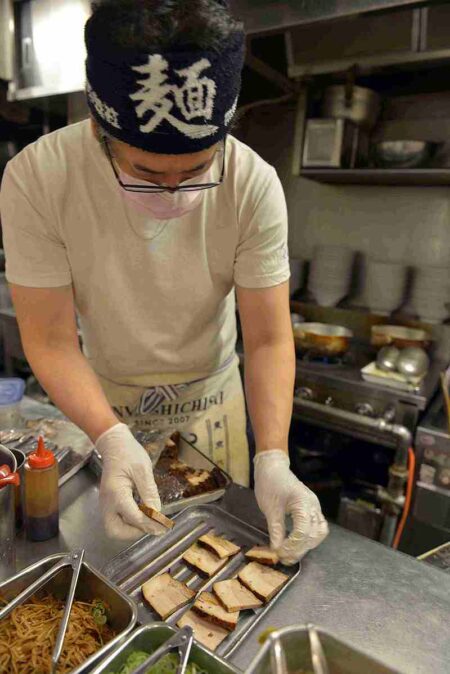

Niboshi niku ramen with a lot of roast pork on top. ¥1470.

0:08 JST, October 19, 2020

There is a ramen shop that makes noodles from scratch only after you order. When I first heard that, I thought, “Seriously?” But then, it might be possible. Some famous Japanese eel restaurants start cooking live eels after they receive an order and then grill them slowly over a charcoal fire. This means it’s not unusual to wait an hour for your food. The customer knows this and enjoys calmly waiting for it over a cup of hot sake. This is all part of the food culture here in Japan.

This ramen shop is called Menya Shichisai — a 10-minute walk straight from the Yaesu Exit of Tokyo Station — and while walking there, I imagined it must take quite some time before the ramen is served. It made me worried about their business since a ramen shop thrives on high turnover. The shop seemed quite busy when I arrived.

The exterior of Menya Shichisai

The shop is on the ground floor of the building

The interior of Menya Shichisai

Meal ticket machine at the entrance.

I bought a special shoyu (soy sauce) ramen meal ticket at the entrance and sat down at the counter. The dish came out in front of me in just five minutes. The noodles were being made right in front of the counter where I sat, so I know it was made from scratch, but how can they make noodles so quickly?

One day in October, I went back to the restaurant to find it out.

Fast and delicious

“We don’t do this as a performance,” said Yoshihiko Fujii, one of the two co-owners of Menya Shichisai. “The main reason is to serve freshly made noodles and enjoy the taste and aroma of the flour itself. We can make noodles in the kitchen in the back, but if you don’t see them, you won’t believe it. Watching noodles being made makes the waiting time more enjoyable as well.”

The first thing staff learn at this shop is how to make noodles. That’s why all the employees, including part-time workers, can make noodles in about three minutes. However, there is a difference in experience. When first learning, the noodles might look good, but they tend to fall apart when put in hot water. Staff members practice making them for themselves and other employees, and when they get a passing grade, they are ready to serve actual customers.

This time, I bought a niboshi niku (roast pork) ramen meal ticket and asked Fujii to show me how he makes ramen.

The staffs started making ramen. Of course, they all wear masks during business hours,

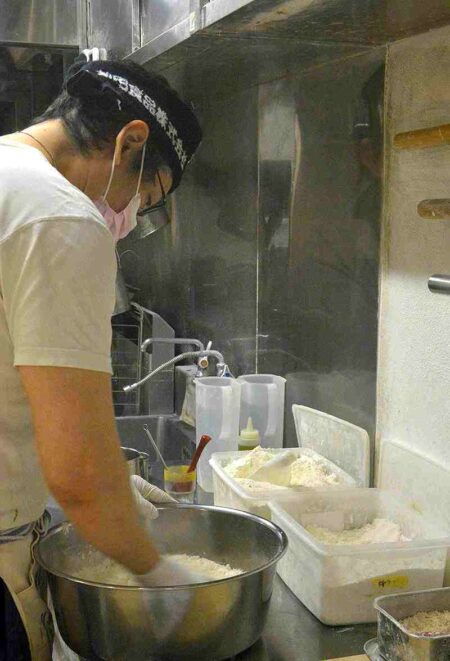

Fujii mixes wheat flour from six different places.

Fujii adjusts lye water to be mixed with wheat flour.

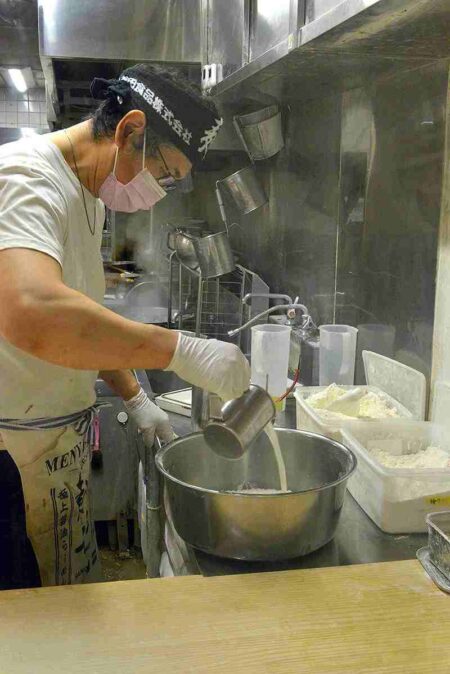

Fujii pours lye water to the tub to mix with wheat flour.

Fujii makes the dough.

The dough is ready to be rolled out.

Fujii rolls out the dough by using the wooden rolling pin.

Fujii made the dough into a square shape.

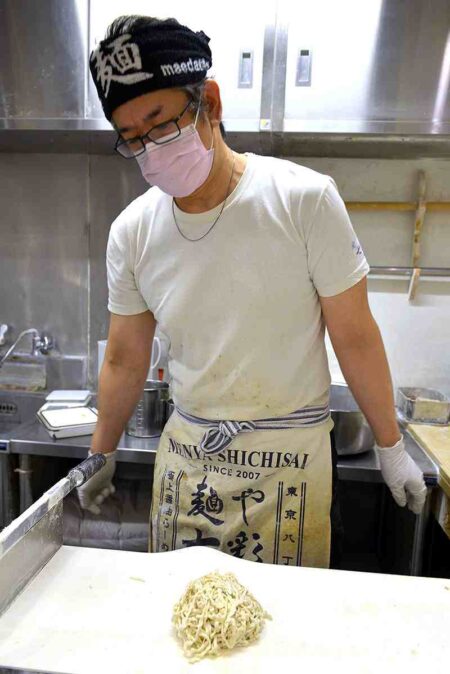

First, he adjusted the lye water, which he then added to a big tub of flour made of wheat from six places in Japan. From there, things went quickly. After a few swift movements of his hands and arms in the tub, it became a lump of dough. Fujii used a wooden rolling pin to then roll the dough out, changing direction several times while moving the pin back and forth. Watching his movements, I was wondering if this is the reason for Fujii’s thick chest. After making the dough a flat square shape, Fujii then carefully folded it up and cut it with a noodle knife. Finally, he squeezed the noodles by hands to make them curly.

This whole process took only five minutes. It was surprisingly fast.

“Our policy is not to knead and not to leave the noodles for several hours or overnight,” Fujii said. “We want customers to enjoy the natural fresh taste and aroma of wheat.”

Ramen shops that make their own noodles usually knead the dough and leave the noodles overnight. However, in that case, the day’s worth of noodles have to be made the day before. Some make them the same day very early in the morning. The taste of the noodles will change over time as well. It is difficult to know how many customers will come, so there might be food waste. At Menya Shichisai, there is no such waste of noodles.

The staff at Menya Shichisai are proud of more than just their noodles. The main soup used for shoyu ramen and shio (salt) ramen is a combination of animal-based broths made from deer bones, brand-name chickens called Tokyo Shamo and fully grown roosters, and a niboshi broth made from dried bonito and mackerel parts. For niboshi ramen, a soup made with dried bonito is combined with the main soup in a 1-to-1 ratio.

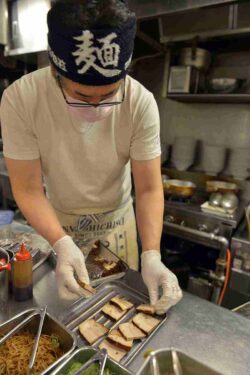

There are two kinds of chashu roast pork, both of which are homemade. One is made from pork belly, boiled for a long time to melt away the fat and make it soft and tender, and the other is made from pork thighs, cooked at a low temperature to keep it moist and juicy, just like roast ham. Both types of chashu can be enjoyed even in the basic Kitakata ramen.

Niboshi niku ramen tastes so good.

The dough is being cut into noodles.

The noodles are squeezed by hands to make them curly.

It’s done.

Fujii prepares chashu roast pork.

Fujii prepares the soup in the bowl.

The noodles are ready.

The niboshi niku ramen was ready in about seven minutes after Fujii started making the noodles. It is the most popular ramen at this restaurant among foreign clientele. The bowl was covered with a lot of chashu roast pork so I had to dig for the noodles underneath with my chopsticks. The soup has a thick taste that was really good. The noodles were firm, smooth and absolutely had a hint of wheat in the taste and aroma.

Menya Shichisai serves ramen based on the Kitakata region of Fukushima prefecture. In other words, the noodles are thick, flat and curly. The chashu roast pork is also fantastic. I ate the whole thing and felt really full. I could understand why this ramen shop is so popular among ramen-lovers.

A traditional charm for raking in good fortune is displayed in the shop.

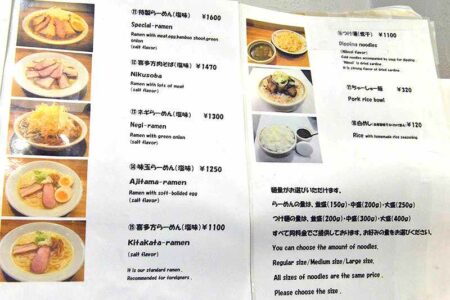

The menu is written in English as well.

Creating culinary culture

Before the novel coronavirus pandemic, 30-40% of the customers were foreigners, with the menu also written in English. There are many reasonably priced hotels around the restaurant where foreign tourists would often stay. Before the restaurant opened at its current location in 2014, it was located on a ramen street inside Tokyo Station and became well-known to many foreigners, many of whom visited Menya Shichisai after reading about it on social media.

Fujii’s dream is to establish a new genre of freshly made noodles and hopes it will continue to grow over the next 100 or 200 years to become an established culture.

“It’s like a thin thread that gets intertwined and grows larger and larger,” Fujii said.

To achieve this, he is training the next generation, but he also teaches other ramen shops the skill of freshly made noodles, not trying to hide his skills.

It is a big story.

Speaking of big, the Tokiwa Bridge area near the Yaesu Exit of Tokyo Station will be the site of the tallest building in Japan, planned to be 390 meters, to be built over the next seven years. It will be a new landmark in the area, which has a long history of its own. And even though Tokyo Station and the surrounding area have rapidly transformed, I have the feeling, contrary to the speed at which the noodles are made, that Menya Shichisai will keep growing steadily and vigorously over a long period of time.

Soy-sauce based Kitakata ramen. ¥1100.

Soy-sauce based special ramen. ¥1600.

Menya Shichisai

2-13-2 Hatchobori, Chuo Ward, Tokyo.

Lunch is served from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., dinner is served from 5 p.m. to 10 p.m. (9 p.m. on weekends and holidays). Closed on the third Tuesday of each month. Only 13 seats, all at the counter. The number of seats may decrease depending on the coronavirus situation.

Futoshi Mori, Deputy editor of The Japan News

Food is a passion. It’s a serious battle for both the cook and the diner. There are many ramen restaurants in Japan that have a tremendous passion for ramen and I’d like to introduce to you some of these passionate establishments, making the best of my experience of enjoying cuisine from both Japan and around the world.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/13-2/19)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review