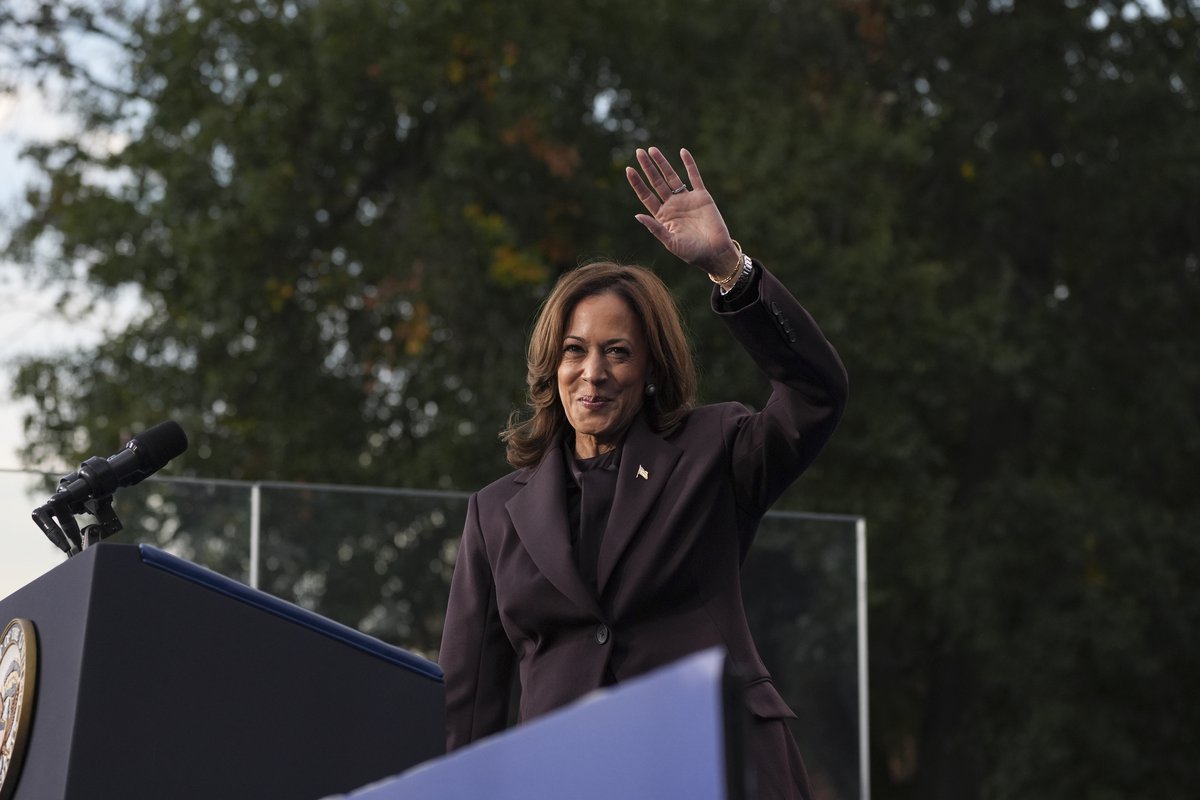

Vice President Kamala Harris delivers her concession speech at Howard University in D.C. after her loss to Donald Trump.

11:57 JST, November 21, 2024

Senior officials with Vice President Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign say her defeat stemmed primarily from dissatisfaction among voters about the overall direction of the country and discontent over inflation and the economy, arguing that those headwinds proved too strong for Harris to overcome in her sprint to Election Day.

The officials also credit President-elect Donald Trump with success in targeting and turning out sporadic voters and using new media sources to speak to them, especially younger men. They acknowledged that Democrats now appear at a disadvantage in their ability to use these newer channels, such as personality-driven podcasts and websites, to reach and motivate potential voters, especially those largely uninterested in politics.

Campaign officials have spent the past two weeks analyzing how a race that their own data suggested was winnable right to the end finished with Trump narrowly winning the national popular vote and a comfortable majority in the electoral college after sweeping all seven battleground states. In the end, Harris was unsuccessful in overcoming the kind of public sentiment that has knocked incumbent parties out of power elsewhere in the world.

“There are certain things we’re looking at to understand if we made the right call,” campaign chair Jen O’Malley Dillon said in an interview. “But fundamentally, there wasn’t just one audience of voters that would have impacted this, or one program. The headwinds were just too great for us to overcome, especially in 107 days. But we came very close to what we anticipated, both in terms of turnout and in terms of support.”

On the eve of the election, the campaign’s internal models showed Harris winning Wisconsin and Michigan by a tiny margin and essentially tied with Trump in Pennsylvania, officials said. Those models showed Harris running behind Trump in the other four battlegrounds: Arizona, Georgia, Nevada and North Carolina.

If Harris had won just the three northern states, she would be president-elect today. Instead, she lost Wisconsin by slightly less than a percentage point, and Michigan and Pennsylvania by slightly less than two percentage points.

“We are very focused on understanding what happened,” O’Malley Dillon said. “We were laser-focused on the battleground states. We knew it would be a margin-of-error race, but with the organization we had and the movement we saw, we thought it was possible.”

Harris’s defeat has prompted both angry finger-pointing and urgent self-reflection among Democrats as they absorb the loss – bitter to many of them – and try to repair a coalition that has been frayed by Trump’s ability to attract working-class voters, including Latino men and some Black men. Initial explanations within the party have been varied and often contradictory, from arguing Harris should have run a more centrist campaign to contending that she should have more explicitly distanced herself from President Joe Biden.

Harris officials, however, say their analysis offers no simple answers or quick fixes, a conclusion that is likely to offer little consolation to dispirited Democrats looking for a path forward.

“I think there’s a lot of the conversation that’s happening that is surmising things, overstating things, ascribing responsibility to things that aren’t really the full, accurate telling of what happened and what that means,” one official said, adding, “The answer is not to pin one group or one part of our party against the other, because it’s not going to be enough to solve or how we move forward.”

The Harris team offered its after-action report during a 45-minute phone conversation, plus responses to follow-up questions. Ground rules called for most of the information to be dispensed without direct attribution to any individual to allow the officials to speak as candidly as possible.

Campaign officials stress that Harris was faced with unique challenges and had just 107 days to deal with all of them. In Trump, she faced an unconventional opponent whose first term in the White House was judged more favorably in retrospect than it was at the time. Trump also drew public sympathy after being the target of two apparent assassination attempts.

Additionally, voters were looking for change, one official said, “and it’s hard to look at Trump and not think that, even at his worst, he doesn’t embody change.”

Harris entered the race July 21, after Biden ended his candidacy under pressure from party leaders following a stumbling debate performance against Trump. She was not well-known and had to introduce herself after a vice presidency in which she initially had been harshly judged. Significantly, she trailed Trump on dealing with the economy and handling the issue of immigration.

Harris advisers point to what they see as some measure of success. Her favorability ratings improved once she became a candidate. She was able to reduce Trump’s advantage on the economy after rolling out a series of policy proposals that went beyond Biden’s agenda.

The officials also said the shift toward Republicans in the battleground states was about half as great as it was nationally, as Democratic turnout in the non-battlegrounds sagged. That has been read by campaign officials as evidence that what they did was working.

But only up to a point. In their analysis, the economy was the overriding issue, as polls had indicated throughout. But Harris advisers also say the country’s overall dissatisfaction was due to what they describe as a hangover from the country’s collective experience during the coronavirus pandemic.

“It was an atmosphere that undergirded people’s general negative feeling about the country and on not feeling like [they were getting] the benefit of some of the progress that had been made,” said one official. “… It is a big part of the shadow that overhung how people felt about the country. It also created a cloud … or a curtain to remembering the Trump time.”

Immigration, too, played a significant role, greater than in past campaigns. As the campaign neared the end, Harris officials could see that its power to sway voters remained strong. Harris tried to address the issue directly with a trip to the U.S.-Mexico border in late September, where she offered some tough prescriptions for illegal crossings.

But the trip was overshadowed by Hurricane Helene and the devastation it wrought in the Southeast. Harris officials concede they were less effective than they had hoped in neutralizing the immigration issue because their messages did not break through.

Harris also sought to make abortion a motivating issue, and for some voters, particularly younger women, it was. But overall, reproductive rights did not have the potency that it had in the 2022 midterms, which came a few months after the Supreme Court had ended the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

Campaign officials said that, in 2022, voters who were weighing both the economy and abortion tended to tip more toward abortion as their motivating issue. In 2024, fewer did so.

Adding to Harris’s challenges, Biden’s approval rating was 59 percent negative on Election Day, and she was never able to break significantly with the president. Asked during an appearance on “The View” where she differed with Biden, Harris said she could not think of anything. Although she tried to run her own race and define herself as part of a new generation, loyalty to Biden and her role as vice president made a true break difficult.

Harris also came under attack from the Trump team for positions she had taken as a presidential candidate in the 2020 cycle, including support for a fracking ban, decriminalizing illegal border crossings and gender-affirming surgery for transgender inmates. Though she repudiated or softened her position on some of those issues, they remained targets.

A Trump campaign ad focusing on transgender issues, which concluded with the line, “Kamala is for they/them, President Trump is for you,” drew significant attention. In a statement, campaign officials said, “There is no doubt that ‘They/Them’ had a negative impact, but we found through extensive testing that answering it in kind – or disputing it – wasn’t as effective, in part because it was in her own words. We neutralized it with other ads.”

But ultimately, Harris campaign officials believe the economy was the pivotal issue. “Our research – both qualitative and quantitative – never showed that these attacks hurt us more than economic contrast with the voters that were open to us,” campaign officials said in a statement after the phone conversation.

Harris campaign officials credit Trump’s strategy for reaching sporadic voters, especially younger men, through podcasts, blogs or social media accounts that one official said are filtered through a media ecosystem with a Make America Great Again “ethos.”

“I think what we have seen is that the folks on the other side, on Team Red, have been doing a lot of this work for years,” the official said. “And there’s just, like, a lot of ground for us to make up in … where young men in particular are going to receive their information, particularly young men who are explicitly not looking for political content.”

The Harris team argues that the vice president made significant progress compared with where things stood when Biden left the race, and say their organizational efforts in the battleground states, in coordination with state Democratic parties, may have helped candidates for Senate hold on even as Harris was losing. Harris had just three months – far less than any major-party nominee in memory – to launch a campaign, introduce herself to voters, deliver a persuasive message and turn out her loyalists.

“We are not here to tell you everything was perfect,” O’Malley Dillon said. “We lost. But some of the ascribing the loss to singular things, like if we had just done [an appearance with podcaster] Joe Rogan, then that would have solved the problem with young men. That is too simplistic and doesn’t solve anything and certainly doesn’t solve the path forward.”

Harris advisers do not see a true electoral realignment, with voters of color flocking toward Republicans, as some analysts have suggested. Even among Latino men, campaign officials said, the shift was more significant in non-battleground states than in those where the Harris campaign made a concerted effort to reach them. But that question will be a continuing topic for debate.

Nor do they see the political environment as static, as Trump heads toward his second inauguration signaling his intent to upend the government, target his adversaries and shatter a variety of norms.

“We have to really look at who is running and how we’re running [in the future],” said one official. “We have to look at how we’re fighting. We have to look at how we hold together underneath what appears to be what we expected with the second term of Trump. I think that’s going to get really complicated. And that, in and of itself, is going to change how people are responding here.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan