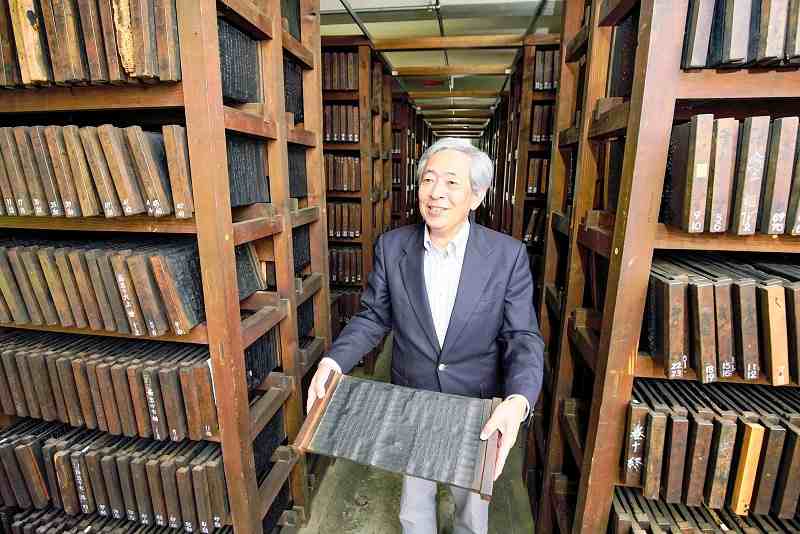

Koichi Saito, representative director of the Onko Academic Society, holds a dual-sided woodblock manuscript used to create Hanawa Hokiichi’s Gunsho Ruijyu.

16:40 JST, May 18, 2021

A statue of Hanawa Hokiichi that was touched by Helen Keller during her visit to the museum in 1937

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the death of Hanawa Hokiichi (1746-1821), a blind Japanese literature scholar who dedicated his life to compiling a historic book collection called the Gunsho Ruijyu. The Hanawa Hokiichi Shiryokan, a museum dedicated to his legacy, is marking the occasion by exhibiting the 17,244 dual-sided woodblock manuscripts he used to assemble the Gunsho Ruijyu, a collection of 666 books containing about 1,300 essays dating from ancient times up to the Edo period (1603-1867) on various subjects including history, literature and medicine.

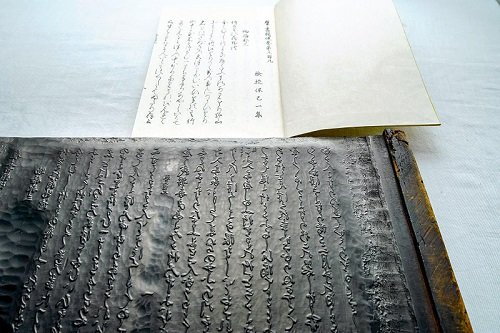

The woodblock manuscript of many famous works, such as “Taketori Monogatari” (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter) and “Ise Monogatari” (The Tales of Ise) are on display. Some can only be seen in this collection.

The stories engraved on the blocks were written in a 20-character by 20-character style.

“This is said to be the origin of the 400-character manuscript,” said Koichi Saito, 66, representative director of the Onko Academic Society, a public interest organization charged with the collection’s upkeep.

These woodblocks, which are a nationally designated important cultural property, are still being used today by Japanese literature and history researchers who want prints made from them.

A woodblock manuscript of “Taketori Monogatari” (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter)

Born in what is now Honjo, Saitama Prefecture, Hanawa lost his sight when he was 7 years old. When he was 15, he aspired to get an education. At the age of 34, he made the decision to collect valuable books, so they would not be lost during a war or a disaster, to give future generations a chance to read them.

He traveled to Kyoto and Ise, Mie Prefecture, to commit numerous essays to memory, and at the age of 74, he completed the assembly of his life work. By comparing and revising manuscripts and preserving them in woodblock form, he was able to pave the way for eventual distribution.

The blocks survived a fire during the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake despite the warehouse, where the blocks were kept, burning down. Saito’s grandfather, the former president of the Onko Academic Society, also fought desperately to save them during the Great Tokyo Air Raid during World War II.

“I believe the reason Hokiichi was able to accomplish such a great undertaking was that the people around him were drawn to his conviction and personality that he never took his disability negatively,” Saito said.

The exterior of the Hanawa Hokiichi Shiryokan museum in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo.

In 1937, Helen Keller, whose mother told her to regard Hanawa as a role model, visited the museum.

“I believe that [Hanawa’s] name would pass down from generation to generation like a stream of water,” the museum’s website quotes her as saying.

The statue that she touched during her visit is still on display today.

Hanawa Hokiichi Shiryokan (Museum of Hanawa Hokiichi)

2-9-1 Higashi, Shibuya Ward, Tokyo

Related Tags

Top Articles in Features

-

Tokyo’s New Record-Breaking Fountain Named ‘Tokyo Aqua Symphony’

-

High-Hydration Bread on the Rise, Seeing Increase in Specialty Shops, Recipe Searches

-

Japanese Students Use Traditional Pickle to Create Novel Wagashi Confectionery

-

My Spendthrift Mother Constantly Asks Me for Money

-

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Craftsman Works to Keep Tradition of ‘Kinran’ Brocade Alive Through Initiatives, New Creations

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts