A ‘Scientific Attitude’ Valuing Empirical Evidence Can Defend Against Influence of Conspiracy Theories

8:00 JST, October 25, 2025

We often hear the term “conspiracy theory” these days, which suggests that powerful forces unseen by society control the world. Conspiracy theories were once considered the domain of a few eccentric individuals, but the rise of U.S. President Donald Trump and the spread of COVID-19 have brought significant changes to society, bringing these theories into greater prominence.

Trump — who has repeatedly made conspiracy-theory-like statements, such as that the concept of global warming was created by and for the Chinese — was inaugurated as U.S. president again in January this year. Now in his second term, he is pushing for budget and personnel cuts at agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is responsible for climate change research. At the U.N. General Assembly on Sept. 23, he insisted that climate change is “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world.”

Furthermore, Trump appointed Robert Kennedy Jr., who has made unscientific claims linking vaccinations to autism, as secretary of health and human services, overseeing health administration. Kennedy too has made baseless conspiracy-style claims about the novel coronavirus. After taking office, he announced plans to phase out messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine development and fired the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These moves have been intended to incorporate his own vaccine-skeptical views into U.S. government policy.

The influence of conspiracy theories is steadily spreading not only in politics but also in scientific fields.

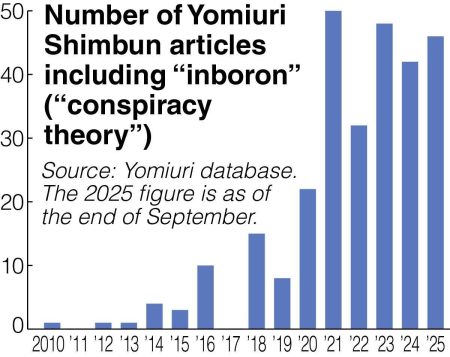

The concept is also beginning to gain traction in Japan. A search of a database of articles from the morning and evening final editions (excluding regional sections) of The Yomiuri Shimbun confirms an increase in articles containing the term “inboron” (“conspiracy theory”) since 2020.

In 2021, a series of Yomiuri Shimbun articles examining unverified claims on social media delved into conspiracy theories.

The series covered not only political and social topics but also scientific hoaxes like the notion that “vaccines cause infertility.” In Japan, social media posts promoting the infertility theory began increasing around April 2021. Conspiracy theories claiming “vaccines are meant to reduce the population” also spread.

An article in March 2023 introduced the suffering of a family in which the mother believed conspiracy theories about the COVID-19 vaccine, such as “it contains poison or microchips.” When parents or spouses become mired in conspiracy theories, a family’s anguish runs deep. The article also shared the family members’ expressions of distress, such as: “They repeatedly claim, ‘The vaccine is a weapon of mass murder’ and yell at family members, ‘Why don’t you understand?’”

It has been said that people who feel alienated may be drawn to conspiracy theories in search of human connection, but the article reveals that falling down a conspiracy-theory rabbit hole can also damage such connections.

How should we address the current situation in which science and conspiracy theories have become intertwined? Lee McIntyre, a research fellow at the Center for Philosophy and History of Science at Boston University, advocates for the concept of a “scientific attitude.”

In his book “The Scientific Attitude,” he explains that such a mindset can be summed up as a commitment to two principles:

(1) We care about empirical evidence.

(2) We are willing to change our theories in light of new evidence.

This embodies the spirit of researchers who test theories against evidence, without clinging to personal views or ideologies.

The advantage of this approach is that it can exclude activities that are “not science.” Science denialism, which is based on ideology and disregards evidence, and pseudoscience, which pretends to be scientific but avoids dealing with scientific evidence, lack a scientific attitude and can be judged as distinct from science.

Of course, even scientists may cling to their own theories or downplay inconvenient data. Conversely, pseudoscience advocates might claim their views are “evidence-based.” Attempting to judge specific individual attitudes risks descending into endless debate. To avoid this, McIntyre proposes evaluating the presence of a scientific attitude not at the individual level, but at the community level.

The scientific community possesses institutions like peer review to scrutinize the content of papers, and practices such as data sharing and verifying reproducibility. Whether intentional or not, when scientists make mistakes, it is the scientific community’s mechanisms that prevent the effects of individual errors or misconduct from spreading. The institutional standards make science trustworthy.

Even the scientific community may face problems, such as authors improperly influencing the peer review process. That is precisely why the scientific community must keep its commitment to being a group with a scientific attitude and demonstrate it to society to gain public understanding.

On the other hand, pseudoscientific groups cannot be said to possess the systems or mechanisms necessary to guarantee a scientific attitude. Whether such a group engages in peer review or data sharing provides clearer evidence than scrutinizing individual attitudes.

McIntyre points out that a scientific attitude is a bulwark against ideological infection. In our modern era where science and conspiracy theories intertwine, undermining the foundations of knowledge, a scientific attitude is an indispensable stance for safeguarding the established traditions of knowledge.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Makoto Mitsui

Makoto Mitsui is a Senior Research Fellow at the Yomiuri Research Institute.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

-

Chronic Issues Erode Thailand’s Economy as Political Confusion Persists, Threatening Terminal Decline in Its Economy

-

Iran Situation: Japan Must Exert Diplomatic Efforts without Merely Standing by

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts