Technological Efficiency Brings Both Ease and Unease; Should Machines Do Things We Like to Do Ourselves?

8:00 JST, June 8, 2024

I will never forget a story I heard 10 years ago, when I had the opportunity to study abroad at the University of California, Berkeley. It was a parable presented in a class for engineering students that I audited.

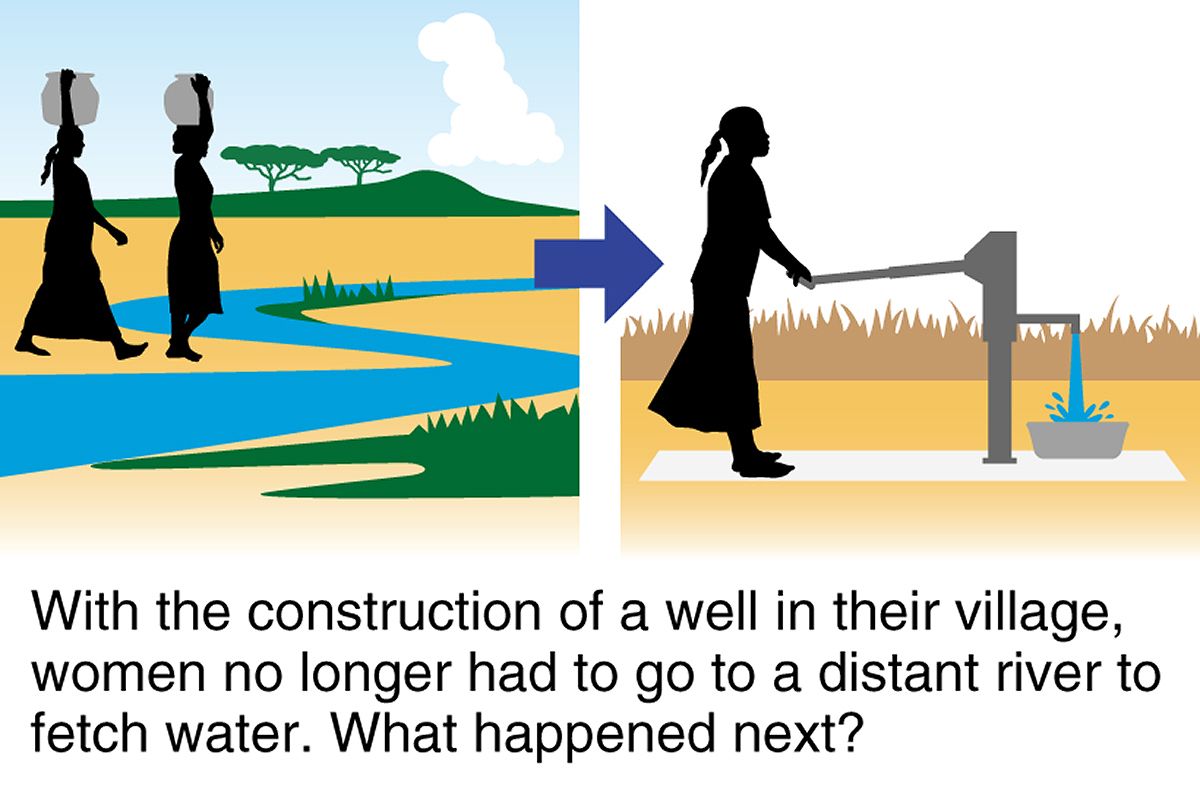

“Engineers from a developed country stayed in a poor village in a developing country for a work project. After finishing their work, they had a few days free. They dug a well in the village to help the local women they had come to respect because they had seen the women walking to a distant river to fetch water. Then the engineers went home. Six months later, they were informed that one of the women who had been freed from her chore of fetching water had committed suicide.”

What went wrong?

The answer given in class was this.

“For the women, the time they spent walking to the river to fetch water with their friends was a time to escape the eyes of their husbands and enjoy light conversation. The construction of the well had deprived them of that time. Now their husbands would not stand for their chatter and time-wasting by the well, in front of their own eyes. The engineers had never imagined any negative implications of their technology; they just wanted to help the women.”

The purpose of the story was to show how technology can have the opposite of its intended effect, depending on the circumstances. Although not as extreme as this, there are examples of advanced technology increasing the pressure on people even today.

Consider the emergence of “miru-sho,” or shogi fans who enjoy watching the game instead of playing it themselves. This is due not only to the popularity of young champion Sota Fujii, but also to the fact that it is now possible to watch the game with real-time analysis by artificial intelligence to help spectators appreciate the state of play. Sometimes, we can see a dynamic development in which the likely outcome of the game is reversed with a single move.

According to Prof. Hitoshi Matsubara of Kyoto Tachibana University, an AI researcher who has had extensive contact with professional shogi players, the strength of AI has already surpassed that of professional players, and the decisive factor in winning or losing is how well they can memorize the AI’s moves for each phase. Professionals no longer contemplate the wooden shogi board to study past games together with their rivals as often as they used to, but instead look at high-performance computers equipped with AI. And they learn from the “model answers” provided by the AI.

Matsubara recounted the lamentation of a middle-aged professional player who said: “Young professionals are good at studying on the computer, and I’ve increased my study by 50%. I have a fear of being left behind if I don’t study that 50% more, but that doesn’t help me win dramatically.”

He then asked the following question.

“You keep saying that AI will make people happy, but are we happy?”

AI has certainly raised the level of shogi, but it has also increased the burden on professionals. This is another unexpected aspect of technology.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Makoto Mitsui

Makoto Mitsui is a senior writer in the Science News Department of The Yomiuri Shimbun

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan