Japan Uses Traditional Techniques to Prevent Forgery of Banknotes; Exhibition Displays Intaglio Printing, Japanese Watermark Technology

Left: An intaglio print of Matsumoto Castle Right: An image made using watermark techniques

16:30 JST, July 28, 2024

A special exhibition titled “The Art by Japanese Banknotes’ Designers” commemorated the issuance of new banknotes and showcased the expertise and artistry of the National Printing Bureau’s staff who produced them.

The exhibition, held at the Tokyo National Museum in Taito Ward, Tokyo, until July 15, featured elaborate works that the bureau staff created to improve their skills.

The bureau produces a variety of items including the Bank of Japan bills and certificate stamps.

As a symbol of Japan’s identity, the banknotes need to have a beautiful design and appearance, but also possess reliable anti-counterfeit technologies. Intaglio printing and watermarks, still largely done by hand by the staff, are some of the techniques used in the banknotes’ production to prevent forgery.

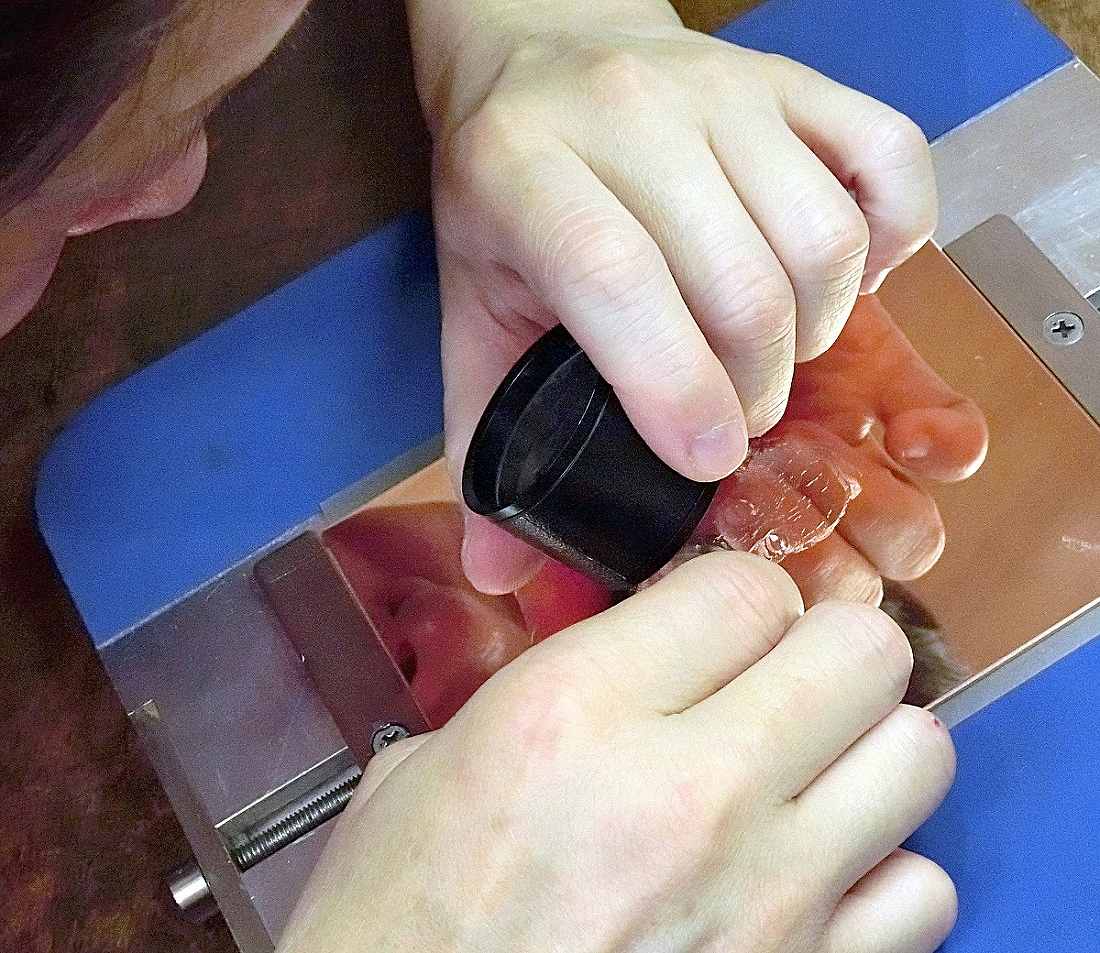

A National Printing Bureau staff member who produces banknotes engraves a metal plate.

Intaglio is a printing technique that is very precise, with a maximum of 10 or so lines per millimeter in a design. An image is drawn from a photograph or other source and transferred onto a metal plate using a needle. Then the lines are engraved using a special tool called a burin. This plate is then used for the printing process in which only the ink in the recessed lines is pressed into the paper, creating the finished product.

The process was developed from a technique used by the Italian artist Edoardo Chiossone (1833-98), who is known for his portraits of Emperor Meiji and Takamori Saigo, a samurai involved in the Meiji Restoration.

Since intaglio printing employs extremely fine lines and the ink is slightly raised on the finished image’s surface, the finished banknotes have a unique texture that makes them extremely difficult to counterfeit.

Another technique employed in the banknotes’ design is watermarks. These can include portraits and letters that are only visible when held up to the light. The technique takes advantage of the fact that the thinner areas of paper appear white while the thicker areas look darker. The banknotes are only 0.1 millimeters thick, demonstrating the high level of skill required.

The watermark technique originated in Echizen, which is in present-day Fukui Prefecture and a well-known production center of washi Japanese paper during the Meiji era (1868-1912). The details of how to the watermarks on banknotes are made have remained a secret.

Both techniques, intaglio printing and the watermark technique, take at least 15 years each to master.

On display at the exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum were 18 intaglio prints of different images such as a castle and 18 sheets of paper with watermarks that included subjects such as a maiko, an apprentice geisha. The industrial art staff of the National Printing Bureau created the works to improve their skills.

About 30 industrial art staff work in four departments, including the intaglio printing and watermark departments. They are not allowed to tell their families or friends about their work. In this respect, the exhibition was a rare opportunity for these workers to showcase their skills.

“I’m grateful that many people know about the techniques developed by our ancestors,” said Kozo Igarashi, chairman of the All Japan Handmade Washi Association.

Makoto Fujiwara, director of the Tokyo National Museum, said at a ceremony: “Japan makes the world’s most elaborate banknotes by hand. I’m happy that our museum can show these traditional techniques.”

The Sumida Hokusai Museum in Sumida Ward, Tokyo, is holding a special exhibition through Aug. 25 that focuses on Katsushika Hokusai’s ukiyo-e print “Kanagawa oki nami ura” (“Under the Wave off Kanagawa”), more famously known as The Great Wave, from his “Fugaku sanjurokkei” (“Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”) series. The work was selected for the back of the new ¥1,000 bill. The exhibition shows the changes in Hokusai’s expression of waves and how the image has persisted as an icon of Japanese culture into modern times.

Work of art in everyone’s pocket

Takashi Uemura, 88, a banknote researcher and author of “Osatsu no Bunkashi” (“Pictorial Encyclopedia of Paper Currencies”) and other works, spoke to The Yomiuri Shimbun about the cultural significance of banknotes.

More than 60% of countries in the world use portraits on their paper currency. This serves to educate the public through a visual understanding of the greatness and achievements of the selected people. National treasures and landscapes are also used for the same purpose. Nowadays, Japan uses portraits of cultural figures. Other countries use portraits of royalty or politicians so they are better known to the public.

The choice of industrialist Eiichi Shibusawa for the new ¥10,000 bill may be a sign that the monetary authorities are looking to him as a model for Japan’s recovery from its long slump.

Using portraits on banknotes can help prevent counterfeiting by taking advantage of the superior ability of humans to recognize different faces. They will feel uncomfortable if someone’s eyes, nose, or mouth look even slightly different from what they know. So, the portraits are finely printed on the banknotes in three-dimensional intaglio prints.

Beautiful paper currency made with various techniques is a work of art that everyone can carry in their wallet. It is important for children to learn what money is like and cannot be replaced by electronic money in this respect. In times of natural disasters, paper currency is still indispensable.

Top Articles in Culture

-

Junichi Okada Wears Three Hats in ‘Last Samurai Standing,’ Serving as Star, Producer, Action Choreographer in Thrilling Netflix Period Drama

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Maison&Objet Kicks off Near Paris with Japanese Lighting Designers’ Installations on Display, Creating Rich Environment

-

Prestigious Japanese Literature Prize Names Toriyama, Hatakeyama as Winners

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time