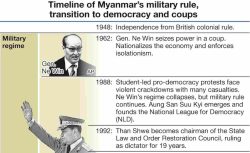

Asia Inside Review: In Myanmar and Thailand, River Divides Hotbed of Scam Centers on One Side, Safe Haven from Military Oppression on the Other

11:13 JST, December 27, 2025

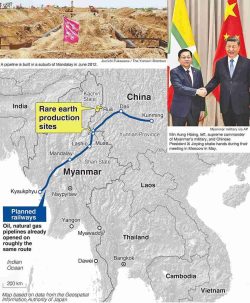

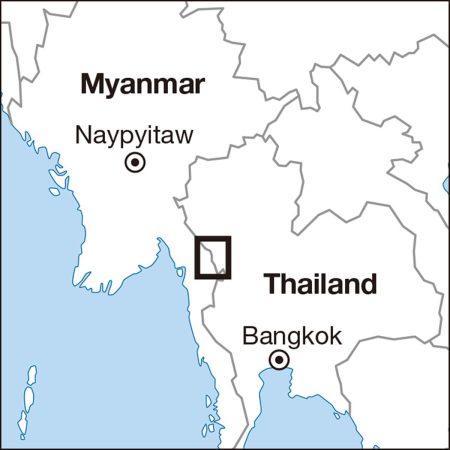

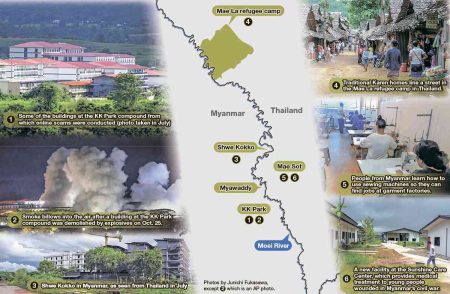

Although separated only by the narrow Moei River, the Myawaddy township in Myanmar and Mae Sot in Thailand could not be more starkly different. The Myawaddy area is one of the world’s biggest hubs of online scammers. The military government that for years turned a blind eye to the activities that went on in Myawaddy has suddenly started to demolish buildings used by scam groups. Across the border, Mae Sot has become a sanctuary for people who have fled from military repression.

When viewed from the hills of Mae Sot, Myawaddy appears as a lawless area that defies description. Housing complexes comprising buildings of all sizes have been constructed here and there among the fields. Against the hills in the distance, they look like a highland research town or a resort. These facilities all belong to China-linked-organized crime groups.

From these compounds, internet users all over the world are targeted through cryptocurrency investment scams, romance scams, illegal gambling and other schemes.

About 10 kilometers south of Myawaddy stands KK Park, a major compound packed with 635 buildings, some of which are at least 10 stories tall. About 10 kilometers north of Myawaddy is Shwe Kokko, a city that China-related companies and other entities have developed as a casino district. Scam centers popped up in Shwe Kokko after the COVID-19 pandemic struck. In places, the river is narrow enough that a ball could probably be thrown across to the other side.

A senior official of a local ethnic minority force said the military-allied Border Guard Force (BGF) of the ethnic Karen people were lending land around Myawaddy to scam groups. “In the past, I never saw any Chinese in Myawaddy, but they’ve built at least 26 compounds in the past five years,” the official said. “It’s just like a Chinese colony now.”

Some facilities there were equipped with electricity transmission towers and antennae that appeared to be for satellite internet services. Washing hung out to dry was visible at apartment buildings. The countless piers on the river are used for shipping in construction materials, illegally traded goods from Thailand, and phone scammers tricked into coming from China, Southeast Asia and Africa by false promises of good jobs.

Crackdown just for show

Criminal groups have been able to act with impunity because the rule of law is practically nonexistent in many areas along the border, with the military taking a hands-off approach. Scam centers moved from a tribal region friendly with the military in Myanmar’s Shan State, which borders China, after Beijing took action to stamp them out. The towns are under military and BGF influence, so it is widely assumed that they are getting something in return from the scam groups.

In January, the BGF and other authorities launched a crackdown on the area in response to pressure from China. However, when I looked across the river from Mae Sot in July, large cranes were constructing multiple buildings in Shwe Kokko and elsewhere on the Myanmar side. The crackdown had been a facade.

The U.S. government has started to treat scams originating in Myanmar as a threat to national security. In November, the U.S. Treasury Department blasted “criminal networks” operating out of Myanmar that “are stealing billions of dollars from hardworking Americans through online scams,” and established a scam center strike force to target scam centers, with a focus on Myanmar as well as Cambodia and Laos.

Meanwhile, the military junta that had previously ignored the problem began demolishing buildings with explosives at the KK Park complex in October, as well as dismantling structures in Shwe Kokko. A top leader of the military government abruptly declared that “rooting out online scams and gambling [was] the responsibility of the state.” A state-run newspaper reported that, as of late December, about three-fourths of the buildings at KK Park had been torn down, and at least 10,000 foreign nationals — mainly Chinese — who were in Myawaddy had been kicked out of the country since January.

Despite this, a senior official of the Karen National Union, an organization of the Karen ethnic minority, was skeptical about the operation. “That was nothing but a show done in response to pressure from the international community,” the KNU official said. “The military hid the ringleaders before it began the demolitions.”

The scam centers had reportedly already started moving from KK Park and other such compounds.

Japan lending a hand

Mae Sot is about a five-hour drive from Bangkok. The population in the surrounding area is estimated at 200,000 to 300,000 people, of whom at least half are reportedly from Myanmar. In addition to immigrants and refugees, many of them fled to Mae Sot following the 2021 coup d’etat.

Nine refugee camps located along the border are home to families of Karen and other ethnic minorities who escaped military persecution around the 1980s. About 30,000 people live in simple houses at the Mae La refugee camp. Mae La, the largest such camp, sits on steep hillsides and narrow strips of flat land. I have visited Mae La four times previously to cover the situation there.

The refugees were prohibited from leaving the camp and working. “Any adult who spends day after day simply waiting for rations to be distributed will lose their self-esteem and will to live,” Katsumasa Yagisawa, a board member of the Shanti Volunteer Association, which has provided support to the camp for many years, told me. That comment has stayed with me. The coup d’etat shattered the dream of these refugees returning to their hometowns, and aid cuts implemented by the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump are beginning to affect the provision of food rations. The sole positive development came in October, when the Thai government lifted the ban on Myanmar refugees getting jobs outside their camps. Yagisawa suddenly passed away in January, but I wish I could have seen the relief on his face had he heard that news.

After the coup d’etat, members of the National League for Democracy, which was headed by Aung San Suu Kyi, also escaped to Mae Sot. “About 140 NLD lawmakers are here,” said 77-year-old elder statesman Han Tha Myint. However, his expression turned gloomy when asked about the whereabouts of Suu Kyi, who has been imprisoned since the coup. “Nobody knows,” Han said.

The New Myanmar Foundation is a private organization that provides humanitarian support to pro-democracy activists who fled with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Sann Aung, executive director of the foundation, said, “We’ve secured temporary housing for them in about 50 places, but it’s still not enough.”

The foundation helps people find homes and jobs within three months, and also teaches them how to use sewing machines so they can work at one of the many garment factories in Mae Sot.

Young people who decided to take up arms against the junta have poured in from Yangon and other places to receive military training in mountain areas under KNU control. The Sunshine Care Center in Mae Sot is a facility that provides medical care to anti-junta fighters wounded in combat. A Karen woman, Nay Chi Lin, converted an old house to create the center. Several new buildings were added to the center in August with assistance from Japan. Previously, the center had a capacity of 130 patients aged from 18 to 30, who had to stay in rows of beds in hot, dark rooms.

Several days before my visit, a young man who had recently returned to his unit died in combat. Another man aged about 20, but who appeared to have a childlike innocence, was staring expressionlessly at a point on the ceiling above his bed.

A young man with injuries to his left eye and left leg was helping out by cooking rice and doing other duties. “I want to participate in the revolution by supporting everybody,” he said.

A 30-year-old man who had been a public employee until 2021 was last year shot in the left leg during a fierce clash in Myawaddy. His leg was amputated below the knee.

“My mother lives far from here and she doesn’t know I’ve lost my leg,” the man said. “I’d be grateful if you didn’t mention my name in your article.”

Junichi Fukasawa

Yomiuri Shimbun Director and Senior Writer

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

AI, Initially a Tool, is Evolving into a Partner – But is it a Good One?

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

-

Greenland: U.S. Territorial Ambitions Are Anachronistic

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture