People look at property ads through the window of a real estate agency in St. Julian’s, Malta, in September.

12:50 JST, December 21, 2021

ST. JULIAN’S, Malta / BRUSSELS — The European Union is calling on its members to review or abolish citizenship programs for investors, also known as golden passport and visa programs.

The EU suspects that the programs, through which wealthy foreign nationals who make high-value investments or purchase expensive real estate can gain citizenship, are being used for money laundering and tax evasion.

Malta, an island state in the Mediterranean Sea, attracts tourists from many countries worldwide for its beautiful beaches and casinos. Mansions stretch along the coastline in the luxury resort town St. Julian’s, but many of the curtains are closed and there are no residents to be seen.

A local taxi driver said nobody lives in them. Chinese and other foreign visitors stay in the country for a week, enjoy meals, casinos, and shopping and then leave, the driver said.

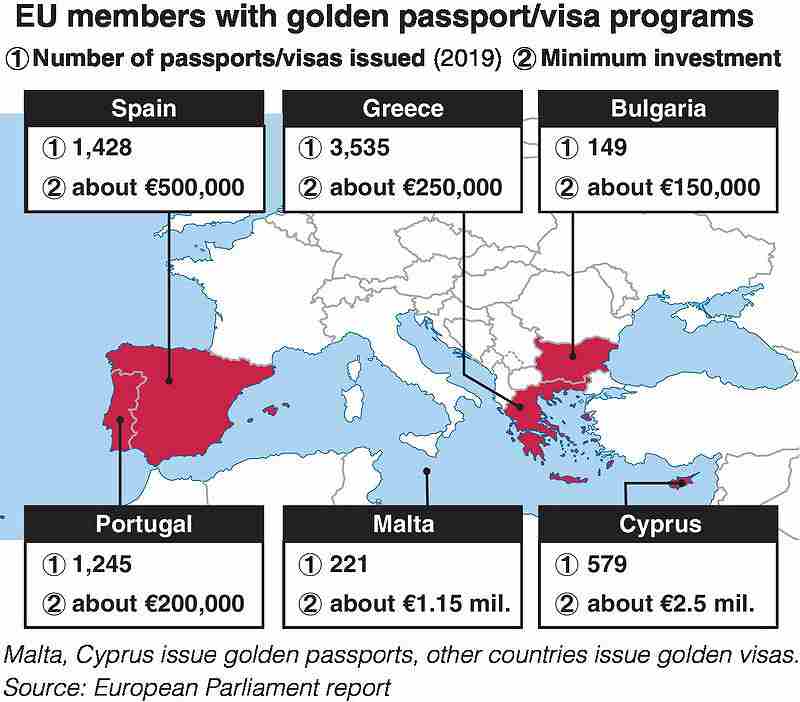

Malta introduced its golden passport program in 2013, granting citizenship to foreigners who meet certain requirements, including five years of residency history, and investing or purchasing real estate worth at least €1.15 million (about ¥147 million).

Malta had approved about 1,200 applications for the passport by June 2019. The total amount of investment and real estate purchases Malta has gained through the program is said to be equivalent to about 2% of the country’s gross domestic product.

Holders of Maltese passports and citizenship gain the benefits of the EU single market — where people, money and services can move freely.

Malta’s income tax rate for wealthy individuals is lower than that of other countries, thus offering the advantage of tax savings.

However, golden passport and visa programs have been overshadowed by reports of irregularities, with citizenship being granted to people who do not meet such requirements as residency history, and allegations of corruption involving influential politicians.

In Cyprus, which also has a golden passport programs, an influential politician was involved in issuing a passport to a Chinese national with a criminal record who was subsequently suspected of money laundering, according to media reports published in October 2020.

It was also found that many foreigners who had obtained citizenship under the program did not live in the country.

The European Union has sounded the alarm over the operation of the programs in Malta and Cyprus, claiming that they are not following procedures to ensure safety under EU law.

In October this year, an investigative body of the European Parliament compiled a report urging the countries to phase out the system, increase taxation and conduct stricter screening.

Jelena Dzankic, part-time professor at the European University Institute, a research institute run by EU member states, said that citizenship is a community of shared values and connections between people to build a better society. The program could lead to a hotbed of crime, which is problematic from the perspective of democracy and human rights, according to Dzankic.

Some countries in the European Union offer golden visas that grant residence rights to wealthy people from outside the EU who make large investments.

Since the euro crisis, which was triggered by Greece’s financial woes, 13 member states including countries in southern Europe have introduced such schemes.

Golden visas have been issued to more than 123,300 people, bringing in about €1.4 billion (about ¥179.5 billion) in revenue to the countries.

Top Articles in World

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

North Korea Possibly Launches Ballistic Missile

-

Chinese Embassy in Japan Reiterates Call for Chinese People to Refrain from Traveling to Japan; Call Comes in Wake of ¥400 Mil. Robbery

-

Pentagon Foresees ‘More Limited’ Role in Deterring North Korea

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged