Japan Surrendered but Then a Kamikaze Crew Flew Out. A Pilot’s Relative Sought to Understand Why He Went.

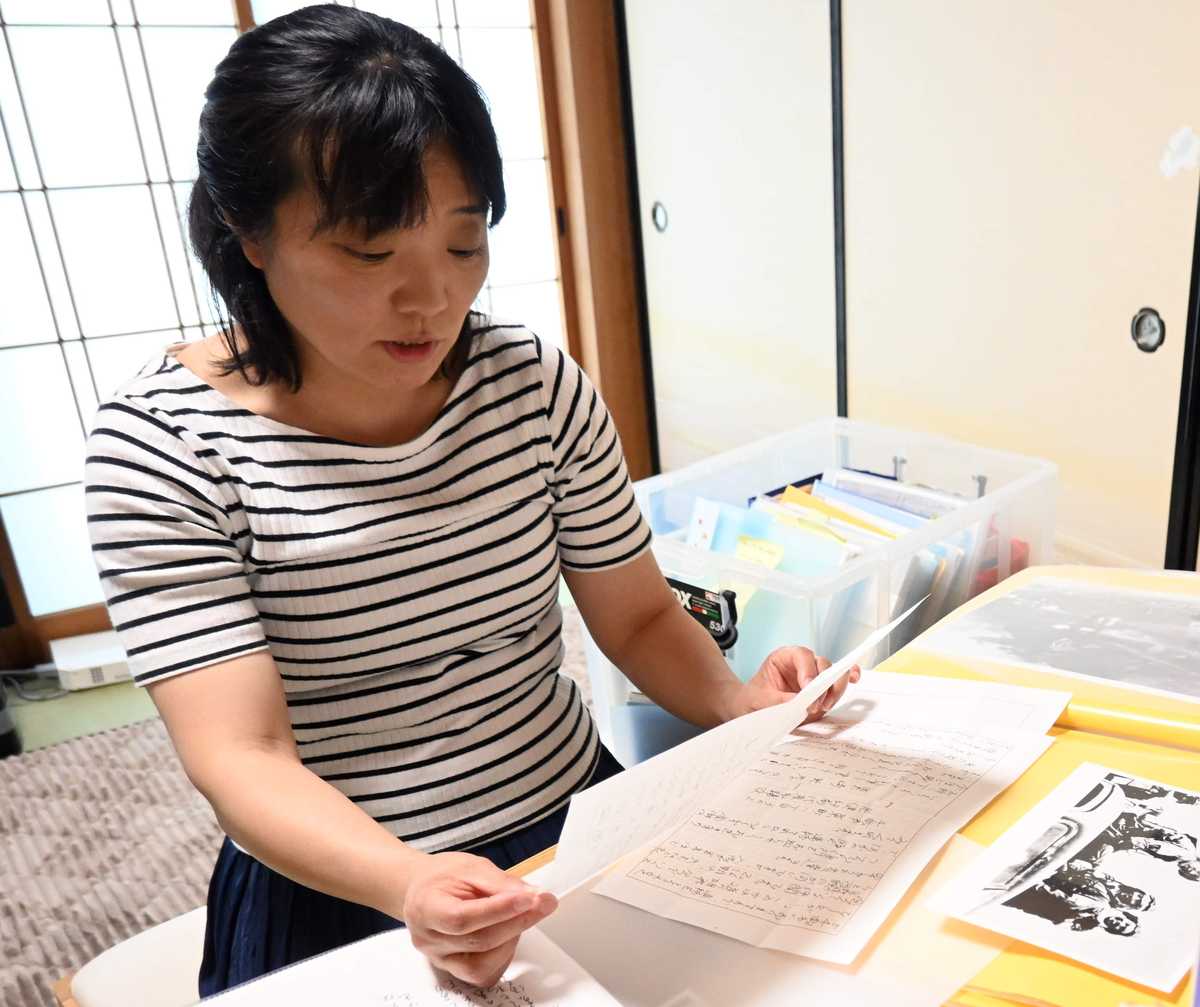

Sachi Michiwaki reads a letter from Fumio Jinba at her home in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, on June 17.

17:45 JST, August 15, 2025

The Emperor announced the end of World War II on Aug. 15, 1945, and shortly afterward Masao Ohki, a 21-year-old senior flight sergeant, took off in a bomb-laden plane. He was a member of the “Ugaki suicide attack.” Although his body has never been found, he is treated as having been killed in action. Sachi Michiwaki, 46, a relative of Ohki’s who lives in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture, wondered why he flew out after the war was over. About 20 years ago, she began researching him.

When Michiwaki was a university student, her grandmother told her, “Masao Ohki was the youngest brother of your great-grandfather,” and she gave Michiwaki an article from a local newspaper about Ohki. “He was a kind and bright man,” her grandmother said.

The Ugaki suicide attack took place about five hours after the Emperor’s noon broadcast, and Navy Lt. Gen. Matome Ugaki, who had commanded suicide attacks in the Battle of Okinawa, led 22 young pilots from the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Oita Air Base to Okinawa. Twenty-three men flew on 11 Suisei bombers, with an 800-kilogram bomb in each aircraft. Eighteen of the men died, including Ugaki. Ohki, a surveillance pilot, was in the rear seat of a plane.

Ohki joined the navy at age 17. However, he left behind no will, and the details of his time in the navy were unknown. “Why did he volunteer for a suicide mission in the first place?” Michiwaki wondered

About 20 years ago, Michiwaki, still thinking of her grandmother’s words, began frequenting the National Institute for Defense Studies, part of what is now the Defense Ministry, as well a publishing company that handles books related to the military. She was introduced to former kamikaze pilots and their relatives. She wrote one letter after another and paid visits. However, she was unable to find anyone who knew Ohki directly. In 2007, she published a book about her research.

The next year, she received a postcard. “I read your book. I was in the same group as Masao Ohki in Iwakuni,” it read.

The postcard was from Ohki’s friend, whom she had been unable to find despite her best efforts.

Ohki’s ‘best friend’

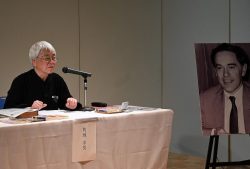

Fumio Jinba talks about Masao Ohki in Atsubetsu Ward, Sapporo, on June 28.

The friend in question was Fumio Jinba, who is now 99 and lives in Sapporo. He was one of Ohki’s “best friends” at the naval pilot training course. “Whatever I did there, it was always with Ohki,” Jinba said.

Jinba passed his flight training course and joined the Iwakuni Naval Air Squadron in Yamaguchi Prefecture in December 1941. During the course, he had roughly 1,200 classmates, but Jinba and Ohki were in the same group of about 20, and they ate and slept together. “I was the tallest, and me and Ohki, the second tallest, were always a pair. We ate, bathed, cleaned and did everything together,” recalled Jinba.

“If we did not meet the standards in classwork or physical education, we were beaten on the rear end with a stick,” he added. They were punished by their superiors even for minor things, such as their daily conduct. In another painful memory, Jinba said he and Ohki once “sat on a stone at the foot of Kintai Bridge and both cried, ‘I want to go home.’”

Jinba speculated on Ohki’s reasons for volunteering for the Ugaki suicide attack. “While he was unsure whether the war was really over, he must have felt that if he sacrificed himself, Japan would be better off and he would be able to protect his family back home. He may have had some hesitation, but I don’t think he would have been able to say no when he had been told, ‘Let’s go.’ If I had been in the same situation, I would have gone, too.”

Jinba then condemned Lt. Gen. Ugaki for taking his men along for the attack.

Hearing Jinba’s story, Michiwaki felt as if Ohki had come vividly to life before her. And she also felt that her journey in Ohki’s footsteps had reached its end.

Keeping memories alive

Masao Ohki, standing beside a woman in the back row, and Fumio Jinba, third from left in the middle row, during their days as flight trainees for the Imperial Japanese Navy, in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Michiwaki got back in touch with Jinba last year after getting married, having children and raising a family. They have exchanged about 20 letters and faxes and met three times.

Last year, her book was republished. At home, Michiwaki has a storage case filled with more than 300 letters and photographs from the dozens of people she corresponded with during the research and publication process.

Now she is experiencing a new surge of determination. “I’m going to pass on to future generations the thoughts of those who lived through the war,” she said.

‘Life is not to be snatched away’

Masao Ohki, far left, and other pilots just before flying off on a suicide mission from the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Oita Air Base in the afternoon of Aug. 15, 1945

Jinba has not forgotten the pain the war brought him.

Late on the night of Aug. 10, 1945, he was adrift on a dark sea. The reconnaissance plane he was flying had crashed into the Sea of Japan after taking off from its base in Rajin (now northeastern North Korea). After drifting for a while, he saw the sun rise and spotted land.

Though he survived, his hardships continued. After the war, the Soviet Union sent him, along with other Japanese soldiers, to a prison camp in Siberia, where he was forced to work in coal mines and cut down trees in the forest. He endured a trifecta of torments: starvation, extreme cold and hard labor.

“Every day, we had to dig out the hard ground to bury our dead comrades,” said Jinba. “The ration was 300 grams of black bread a day. It was extremely paltry. Grass, grasshoppers, rats. We ate everything.”

He returned home in August 1947 and shared his war experiences while teaching social studies at schools.

“Life is not something to be snatched away. It is something to be nurtured. War must never be allowed,” insisted Jinba.

Of Michiwaki, whom he continues to correspond with, he said, “I respect her for how active she’s been, doing thorough research, writing a book about it and passing it on. That is what keeps the late Ohki alive,” he said.

A video of Jinba’s interview is available on Yomiuri Shimbun Online. To access, click the URL.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

-

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/13-2/19)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review