Kishimoto Shokudo / Traditional Okinawa shop that rose from, and now thrives on, ashes

Large size serving of Okinawa Soba. ¥750.

16:16 JST, November 12, 2020

As soon as I came out of Naha Airport, the main point of entry into Okinawa Prefecture, the tropical air enveloped me. The temperature was a balmy 26 C. Clear skies. I would no longer need the jacket I had on when I left Tokyo. Walking around the city, I broke out in a sweat.

The tension that builds up living in the metropolis gradually eased, and my body and mind were engulfed by the Okinawan climate. Even the cicadas’ loud noise was soothing.

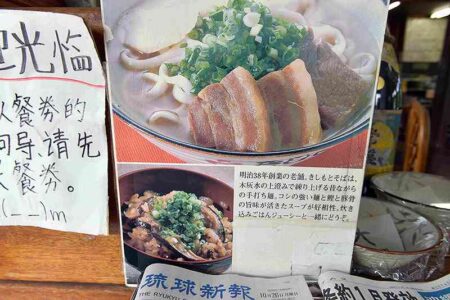

My destination was Kishimoto Shokudo, the first ramen shop outside of Tokyo to be introduced in Ramen of Japan. Founded in 1905, the 38th year of the Meiji period, the shop’s most distinctive feature is that natural alkaline water made from the ashes of burned wood is used to make the noodles. This is one of only a few places in Okinawa that still maintains this traditional Okinawan noodle-making process.

I rented a super-cheap rental car — ¥10,000 for three days with unlimited mileage — and headed north. It took about two hours from Naha to Motobu, which is near the Churaumi Aquarium, a tourist attraction in the northern part of the Okinawa main island. Kishimoto Shokudo is located near the market of the once-bustling small port town.

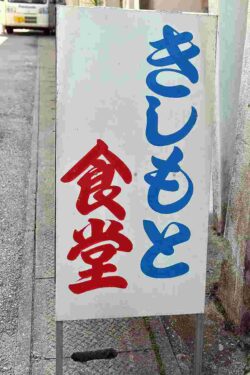

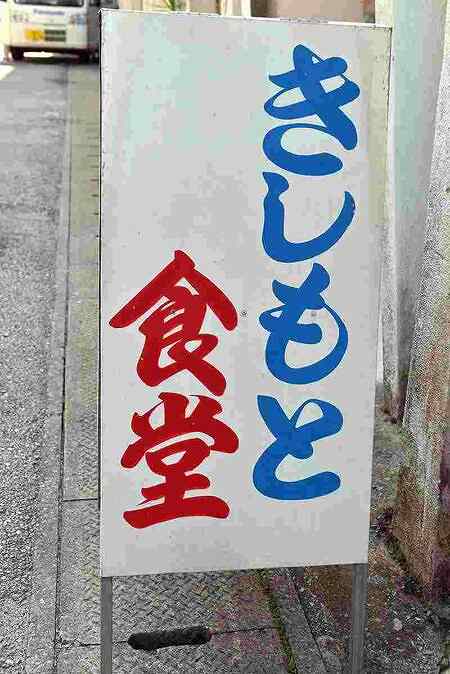

The entrance of Kishimoto Shokudo

There is a sign on the street in front of the market that directs you to the parking lot of Kishimoto Shokudo.

Hiroki Nakahodo, the fourth-generation owner, smiles in the main shop of Kishimoto Shokudo.

Seeing the exterior of the shop, I could easily get an idea of its long history. And when I spoke to fourth-generation owner Hiroki Nakahodo, 42, I realized that the restaurant’s history overlaps that of Okinawa. More about that later; let’s get to the ramen.

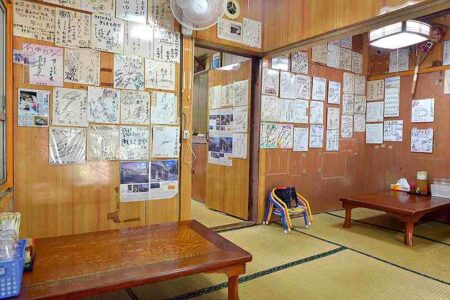

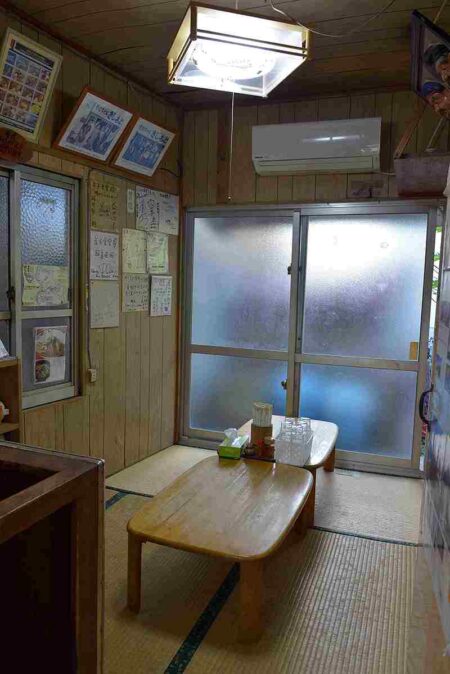

You take off your shoes and come up tatami seating tables. The walls are adorned with signatures from various famous figures who have visited the shop.

The interior of Kishimoto Shokudo’s main shop.

A staff of the main shop is busy preparing for the lunch time.

The kitchen of the main shop. Noodles are made in the branch shop and brought here.

In a large pot in the main shop kitchen, rafutee was being cooked.

The menu of main shop. You choose the size of Okinawa Soba from large or small. Okinawa-style cooked rice Jyu-si is ¥300.

Photos of famous figures who visited the shop.

The sign of Kishimoto Shokudo outside the main shop. Very simple.

Traditional noodles made from wood ashes

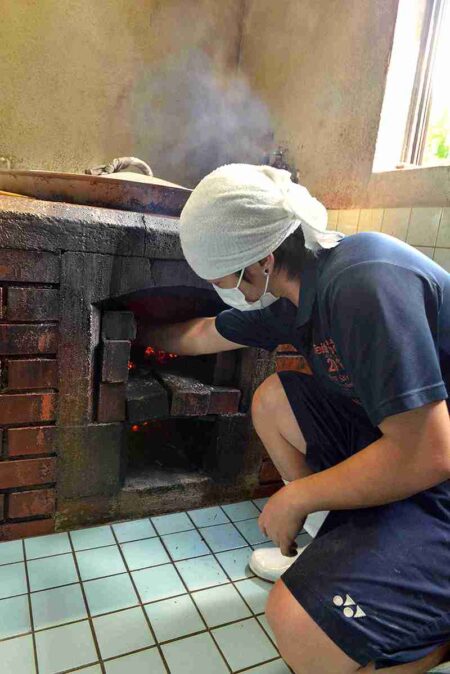

Kishimoto Shokudo’s signature noodles are not made in the main shop, but at a branch that has much more space. Nakahodo took us to the branch, which was about a five-minute drive away. It opened about 17 years ago, has a large parking lot and has more seating for customers than the main shop. At the far end of the kitchen, there was a large pot for boiling the noodles, and pieces of wood were constantly being fed into the old-fashioned wood-burning stove.

Yaedake branch shop has spacious parking lot and more seating tables.

Pieces of wood were constantly fed into the old-fashioned wood-burning stove.

“These are the ashes,” Nakahodo said, showing me a bucket of what looked like yellowish powder that had been taken from the stove. The ashes looked beautiful and clean. “We remove the impurities. The flavor of the noodles differs depending on the kind of wood that is used.”

Nakahodo mainly uses wood from the Itajii (a kind of fagaceae) tree, a broccoli-shaped tree that grows wild in the forests of Yanbaru in the northernmost part of Okinawa’s main island. “It smells so good,” he said. In the evening, the ashes taken from the stove are placed in a large bucket filled with water, and allowed to slowly settle overnight. The water above the settled ashes is used to mix with wheat flour to make the homemade noodles.

“This water has a lot of natural minerals from the ashes, and we’ve been making noodles this way for over a hundred years,” Nakahodo said. He scooped up water from the bucket and invited me to touch it. Rubbing it between my thumb and forefinger, it felt a little viscous. “The natural minerals are dissolved into the water and the pH is strong,” he said.

The ashes that had been taken from the stove.

This is when the ashes are put into the water.

The ashes settle to the bottom of the water over time.

After more hours, the water becomes clearer. The water above the settled ashes are used to make homemade noodles.

Boil a lot of noodles at once.

The staff opened the lid of the large pod.

The noodles are put into the boiling water.

Mix the noodles in the large pod.

Ramen in Okinawa is called “Okinawa Soba,” and it the only type on the Kishimoto Shokudo menu. The only choice is the size: small, large or extra large. I ordered the large, which is the normal size. The noodles, boiled in the cauldron, are already apportioned in the bowls, ready for the busy lunch hour. When an order comes in, a young staff member takes the noodles from the bowl and puts them into a first pot, which Nakahodo said was to remove oil from the noodles. Then it goes in a second pot to season the noodles with the soup.

The noodles are already apportioned in the bowls for the busy lunch hour in Yaedake branch shop.

The noodles are put into the first pod to remove oil from the noodles.

The noodles are put into the second pod to season the noodles with the soup.

Noodles are ready.

A red meat to put on the noodles.

Three pieces of meats are put for the large size Okinawa Soba(right), and two pieces for the small size.

A cooking staff is pouring the soup into the bowls.

Finally, topped with a spring onion.

The soup is made from bonito flakes, with a little bit of broth made from pork bones added. The “large” serving is topped with two slices of the Okinawan specialty rafutee (cooked pork belly), and one piece of red meat, both homemade. White kamaboko (fish paste) made from a local fish called gurukun (double-lined fusilier) and green onions are added. The “small” has one piece of rafutee and one piece of red meat. The “extra large” is topped with a total of five pieces of meat.

The noodles, steeped in the bonito broth, are flavorful and have adequate firmness. I felt a sense of satisfaction that I was eating noodles that have been unchanged for 115 years. The soup was mild with a pleasant and strong aroma of dried bonito flakes. The soup and the noodles were perfectly balanced. The traditional Okinawan rafutee was so well seasoned and delicious that it made me want to eat a lot more. Moreover, they were glistening brightly. The kamaboko was plump and very fresh. All of the ingredients are well represented in the bowl, making it a very satisfying dish.

Large size serving of Okinawa Soba.

The rafutee pork belly are shining with deliciousness.

The interior of Kishimoto Shokudo branch shop.

It can seat up to 50 people, but right now under the coronavirus pandemic, about half of the seats are available.

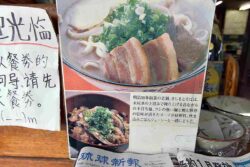

The paper explains the characteristics of the ramen at Kishimoto Shokudo. The picture on the bottom left is Jyu-si rice.

115 years of history

The former Ryukyu Kingdom of Okinawa was conquered in the 17th century by the Satsuma han (feudal domain) in what is now Kagoshima Prefecture, and placed under their control. After the Meiji Restoration, it became the Ryukyu han and the Kingdom ceased to exist. Following the abolition of the han system and establishment of the prefecture system, it was changed again to the present Okinawa Prefecture.

Nakahodo’s great-grandfather, a lacquerware craftsman in Naha, found it difficult to make a living amid the social turmoil after the abolition of Ryukyu han, so he relocated to Motobu. At that time, there was no north-south land route on the Okinawa mainland, so his great-grandparents took a boat from Naha and settled down near the port in Motobu.

The entrance to the market. The bustle of the past is gone, and many of the shops remain shuttered due to a lack of successors.

The yellow market sign stands out even from a distance.

The fresh fish stores across the street from the market are open for business.

The bonito sculpture in front of the market tells the story of how this place was once a thriving landing port of fish boats which caught bonito.

However, his lacquerware did not sell well. At the harbor, boats were loaded with cattle, firewood, and flour, to be sent south to Naha, where Shuri Castle was located. Ships arriving from Naha would bring supplies with everyday necessities. It was Nakahodo’s great-grandmother who came up with the idea of opening a ramen shop after observing the port, which was always crowded with people. She used to make ramen for her husband’s customers in Naha, which drew high praise. The flour and firewood needed to make ramen were both available in the nearby market in Motobu.

The shop thrived, drawing in cattle dealers, firewood workers and women peddling bonito flakes. The origin for the bonito-based soup was that the port was a landing point for fishing boats which caught bonito, making fresh bonito flakes always available at a reasonable price.

The business was successively run by three generations of Nakahodo women: his great-grandmother, grandmother and mother. During the Pacific War, the shop burned down three times, a victim of air raids and battles after the U.S. forces landed on the island. During the post-war U.S. occupation of Okinawa, Kishimoto Shokudo continued to serve the local people.

When I was a high school student, I spent a year from the summer of 1983 as an exchange student in the U.S. state of New Jersey. My host family mother was an Okinawa native. She was a very strict but warm-hearted person. After the war, she met and married my host father, who was stationed in Okinawa as a U.S. soldier, and moved with him to the United States. She must have had Okinawa Soba growing up in Okinawa.

Nakahodo is already thinking about keeping the legacy alive. “I have seven children,” Nakahodo said with a smile, “My 18-year-old son, who I had hoped would be the fifth generation owner, has gone to college in Tokyo and will not be taking over the business.”

He wanted to have another boy to inherit the business, but the next five were all girls. Finally, the seventh child was a boy. He is only 4 years old now. Cherished by his elder sisters, he has been told from time to time, “You’re going to be the fifth generation owner,” to which he dutifully replies, “Yes, I will.” Nakahodo, looking to keep the light of Kishimoto Shokudo from extinguishing, is determined not let his younger son go to a university in Tokyo.

The sea off Okinawa near the shop offers a beautiful view.

You may also enjoy Okinawa soba in an alleyway like this one in the market of Naha, capital city of Okinawa prefecture.

On Naha’s bustling Kokusai street, Shisas statutes, Okinawan guardian lions, were also wearing masks.

Kishimoto Shokudo

Main shop: 5 Toguchi Motobu, Okinawa.

Open 11 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Closed on Wednesday. Yaedake branch: 350-1 Inoha Motobu. Open 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. No holidays.

Small ¥600, large size ¥750, and extra large ¥850. Okinawan-style cooked rice Jyu-si ¥300.

Futoshi Mori, Deputy editor of The Japan News

Food is a passion. It’s a serious battle for both the cook and the diner. There are many ramen restaurants in Japan that have a tremendous passion for ramen and I’d like to introduce to you some of these passionate establishments, making the best of my experience of enjoying cuisine from both Japan and around the world.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/13-2/19)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review