Hiroshima Witnesses: Hibakusha Win Nobel Prize / Next Generation Carries on Will of Hibakusha; Work Toward Abolition of N-Weapons Must Continue After Peace Prize Win

Mitsuhiro Hayashida speaks with a high school student in Nagasaki on Oct. 12.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

6:00 JST, October 21, 2024

Next year will mark the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of the two cities. Looking back on the steps taken by the atomic bomb survivors, known as hibakusha, we will consider the challenges of the coming age without them in a series of articles. This is the second and last installment of a series.

***

HIROSHIMA — “One day, the hibakusha [atomic bomb survivors] will no longer be among us as witnesses to history,” the Norwegian Nobel Committee said during the Oct. 11 announcement of Nihon Hidankyo, or Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations, being selected for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The number of people with atomic bomb survivor’s certificates is likely to fall below 100,000 in 2025 — 80 years after the atomic bombings.

The figure has decreased by about 86,000 over the past decade. As the “era without atomic bomb survivors” is approaching, how can the horror of that day be passed on to the next generation so work toward the abolition of nuclear weapons can continue?

The day after the Nobel Peace Prize was announced, a workshop on peace was held at the Nagasaki prefectural government office.

Third-generation hibakusha Mitsuhiro Hayashida, 32, told 17 high school students from Nagasaki and Hiroshima who attended the workshop: “There are people in the world who see nuclear weapons as ‘heroes.’ Hibakusha have been appealing for a long time for this perspective to change.”

Hayashida, whose grandfather was exposed to the atomic bomb in Nagasaki, has been involved in activities such as petition drives for the abolition of nuclear weapons since high school. He went on to study at university in Tokyo, where he met Terumi Tanaka, 92, a cochairperson of Nihon Hidankyo from Niiza, Saitama Prefecture.

At the age of 13, Tanaka was 3.2 kilometers from the hypocenter in Nagasaki and lost five of his relatives. As Hayashida developed a closer relationship with Tanaka, he was moved by his strong desire to continue talking about his experience of the atomic bombing, even though it must have been something he wanted to forget.

Hayashida spearheaded the international petition drive for nuclear abolition launched by Nihon Hidankyo and other organizations that collected more than 13 million signatures over about four years to the end of 2020.

He returned to Nagasaki in 2021 and founded a general association to develop peace education in his hometown. He focuses on activities such as guiding visitors through bombed-out ruins and giving lectures at educational institutions.

“Receiving the peace prize should increase interest in hibakusha. I want to increase the number of people who continue to think about peace and nuclear abolition as something that concerns them personally,” he said.

Lasting effects

Yuta Takahashi is pictured during a meeting with his colleagues in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo, on Oct. 13.

The passion with which hibakusha speak about their experiences has the power to be an inspiration to people.

Yuta Takahashi, 24, is the representative director general of the incorporated association Katawara based in Yokohama, which advocates against the threat of nuclear weapons.

When he was in the third year of junior high school, he met Sunao Tsuboi, who was then chairperson of Nihon Hidankyo and already close to 90 years old. Takahashi said he was overwhelmed by the sight and passion of Tsuboi as he put his all into talking about the devastation caused by the atomic bomb. Tsuboi died in 2021 at 96.

Takahashi interviewed Tsuboi directly over two days and created a booklet about his experiences when he was in his second year of high school.

When Tsuboi, who usually spoke with his back straight, talked about the discrimination he experienced when looking to marry, he hunched over and began to cry. Seeing this, Takahashi realized that the atomic bomb had not only caused direct damage, but also continued to inflict deep emotional scars on people’s hearts.

Takahashi recently said he was shocked to overhear a group of high school girls talking about how they did not like grotesque things such as the exhibitions at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The Nobel Peace Prize was announced soon after.

“I felt that I will have to tell the story in a way that invokes the faces of hibakusha in the minds of the audience,” he said.

‘Never again’

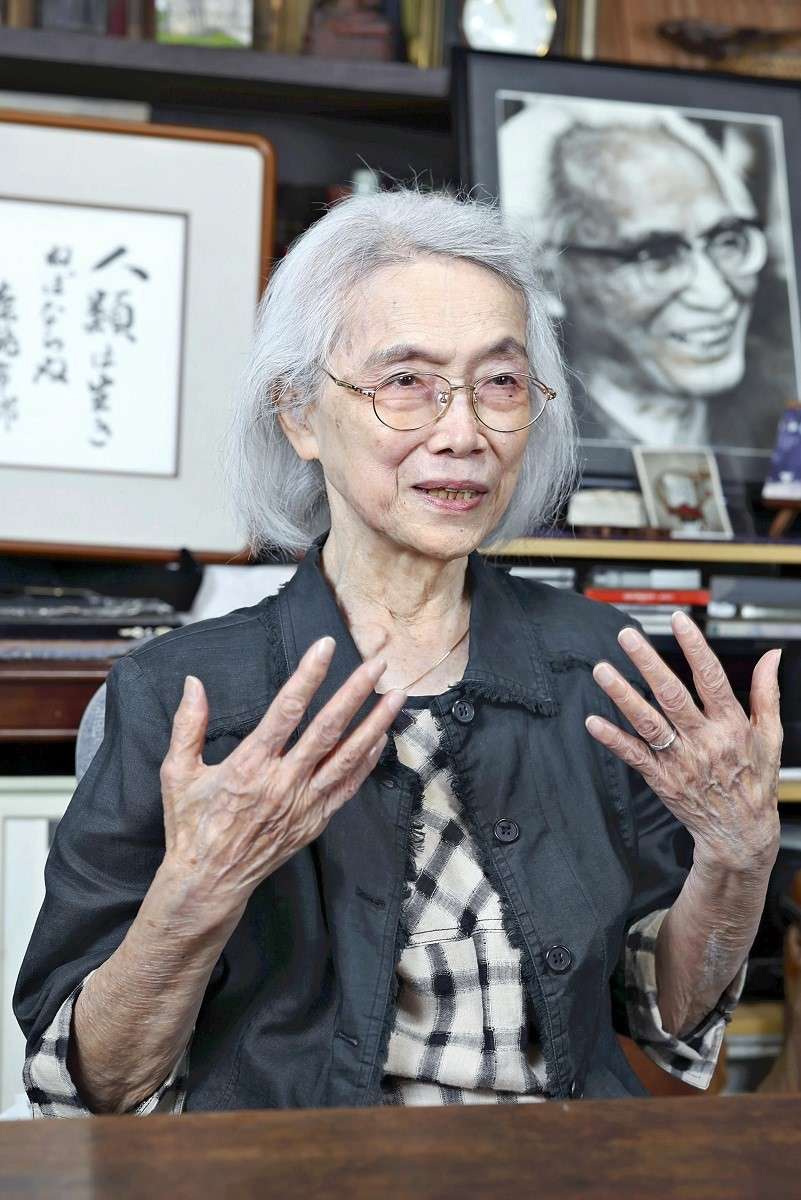

Ichiro Moritaki

Efforts that transcend generations and borders are essential to move closer to a “world without nuclear weapons.”

Haruko Moritaki, 85, plans to hold the World Nuclear Victims Forum in Hiroshima in the autumn of next year, inviting not only Japanese victims but also people from around the world who suffered as a result of nuclear testing during the Cold War.

Haruko is a daughter of Ichiro Moritaki, an atomic bomb survivor who is known as the “father of the antinuclear movement.” He died in 1994 at the age of 92.

Ichiro, who lost sight in his right eye due to the atomic bombing, used to sit with his back to the Atomic Bomb Victims Cenotaph at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park every time a nuclear test was conducted. He did so about 500 times.

Haruko remembers her father saying, “I carry the souls of the victims on my back,” when asked by overseas media why he did it.

“We must not be satisfied at receiving the Peace Prize. We must remember the all-out efforts of our predecessors. Now is the time to make the world aware of the horror of nuclear weapons and to take steps toward their abolition,” Haruko said.

Nihon Hidankyo, in its founding declaration in August 1956, declared, “Humanity must never again inflict nor suffer the sacrifice and torture we have experienced.”

Popular Articles

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Japan High School Boys Set New Record in Relay Race; Winning Girl...

-

Japanese Public, Private Sectors to Partner on ¥3 Tril. Project t...

-

Japanese Actor Ken Watanabe-Backed Cafe to Close in Coast Town Hi...

-

Japan, China Continue Trading Barbs Over Radar Incident; Tokyo Re...

-

Rubio Seeks to Balance Relations With Japan, China; Says China Wi...

-

Nomura HD Aims to Increase Number of Individual Clients Through E...

-

Popularity of Piggy Banks Across Time and Place Seen at Bank's Mu...

-

Japanese Lawmakers Support Continued Ban on Sports Betting

Popular articles in the past week

-

Israeli Tourists Refused Accommodation at Hotel in Japan’s Nagano...

-

Tsukiji Market Urges Tourists to Avoid Visiting in Year-End

-

U.S. Senate Resolution Backs Japan, Condemns China's Pressure

-

Kenta Maeda Joins Rakuten Eagles; Returns from American MLB to Ja...

-

Sharp Decline in Number of Chinese Tourists But Overall Number of...

-

China Attacks Japan at U.N. Security Council Meetings; Representa...

-

Japan Set to Participate in EU's R&D Framework, Aims to Boost Coo...

-

Japan Backs Public-Private Cooperation on Economic Security; Nati...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nu...

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by...

-

Tokyo Economic Security Forum to Hold Inaugural Meeting Amid Tens...

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Securit...

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi's ...

-

Govt Aims to Expand NISA Program Lineup, Abolish Age Restriction

-

Blanket Eel Trade Restrictions Rejected

-

Key Japan Labor Group to Seek Pay Scale Hike

"Society" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

M4.9 Earthquake Hits Tokyo, Neighboring Prefectures

-

Israeli Tourists Refused Accommodation at Hotel in Japan’s Nagano Pref., Prompting Protest by Israeli Embassy and Probe by Prefecture

-

M7.5 Earthquake Hits Northern Japan; Tsunami Waves Observed in Hokkaido, Aomori and Iwate Prefectures

-

Tsukiji Market Urges Tourists to Avoid Visiting in Year-End

-

M5.7 Earthquake Hits Japan’s Kumamoto Pref., Measuring Upper 5 Intensity, No Tsunami Expected

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant; Inspects New Emergency Safety System

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by Deterioration of Japan-China Relations

-

Tokyo Economic Security Forum to Hold Inaugural Meeting Amid Tense Global Environment

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Security in Interview Ahead of Forum

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi’s Power Plans