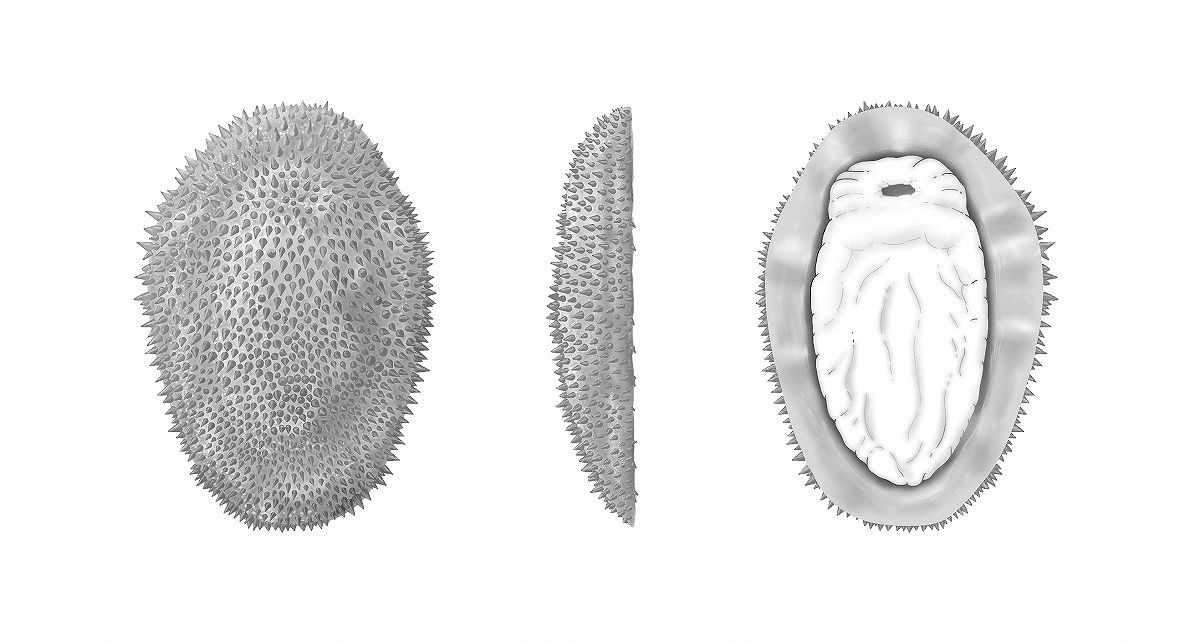

An artist’s reconstruction of the Shishania aculeata, as it would have appeared in life as viewed from the top, side and bottom (left to right).

16:09 JST, August 8, 2024

WASHINGTON (Reuters) — Earth’s roughly 76,000 species of mollusks come in an impressive variety of forms including clams, oysters, scallops, mussels, snails, slugs and even some possessing exceptional intelligence such as octopuses, cuttlefish and squid. But their ancestral form and early evolutionary history have been tough to decipher.

Fossils discovered in southern China of a curious little marine creature that lived during the Cambrian Period about 514 million years ago — essentially a spiny slug — are now providing some clarity about the initial stages of the mollusk lineage.

The newly-identified species, called Shishania aculeata, had a flattened oval-shaped body averaging a bit more than three centimeters long and eight-tenths of two centimeters wide. Some of the 18 specimens described by the researchers preserved soft body parts that rarely become fossilized, providing an unusually detailed accounting of its anatomy.

The top of its body was densely covered with hollow, cone-shaped spines — resembling those on durian fruit, indigenous to Southeast Asia — for protection from predators. The spines are made of chitin, the same material as crab shells.

“On the bottom side, we see a ring of tissue called a girdle that surrounds an organ called a foot. This is the same feature as the slimy, muscular sole that you see in slugs and snails. It would have used this to creep around a muddy seafloor much like slugs and snails do on land today,” said paleontologist Luke Parry of the University of Oxford, one of the leaders of the study published in the journal Science.

“It may have fed in a shallow marine environment on algae and other organic matter it could find,” added paleontologist Xiaoya Ma of Yunnan University in China and the University of Exeter in England, another of the study leaders.

The anatomical features of the underside of its body demonstrated that it is one of the earliest-known members of the mollusk lineage.

Mollusks are a diverse group of invertebrates, second in size in the animal kingdom only to arthropods, the group spanning insects, spiders, lobsters, crabs, centipedes, millipedes and others. Mollusks have soft bodies composed almost entirely of muscle, boast a well-organized nervous system, and usually are protected by a shell. Those lacking a shell, like squid, come from lineages that previously had one.

“So this new fossil records what mollusks looked like before they evolved their shells,” Parry said. “It tells us that early mollusks were covered by protective spines. We found evidence of the cellular mechanism through which Shishania secreted its protective spines by looking at them with an electron microscope. We found that they contained tiny elongate channels that are less than a thousandth of a millimeter in diameter.”

The invertebrate group that includes earthworms also has this type of secretion system.

Shishania’s remains were found by study lead author Guangxu Zhang when he was a doctoral student at Yunnan University, rescuing fossils in earth dug up in a Yunnan Province road construction project.

“I saw under the magnifier that I had with me that the fossils seemed strange, spiny and completely different from any other fossils that I had seen,” Zhang said.

Other fossils at the site included sponges and horseshoe crab-like trilobites that shared Shishania’s marine realm.

The great diversity among modern mollusks, in body shape and lifestyle, has made it difficult to elucidate their last common ancestor and early evolutionary steps. Their diversity evolved rapidly during an evolutionary event called the Cambrian Explosion, a critical juncture in the history of life on Earth when a dizzying array of animals first burst onto the scene.

Parry said Shishania should be viewed as “an evolutionary aunt or cousin” to today’s mollusks, retaining a body plan more primitive than the actual last common ancestor for all members of the group now alive.

“I think it’s amazing that we can trace animals that are clever enough to use tools like octopuses back to humble slug-like beginnings over half a billion years ago,” Parry said.

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

-

iPS Cell Products for Parkinson’s, Heart Disease OK’d for Commercialization by Japan Health Ministry Panel

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan