Persecution and Apology in Brazil / Japanese Brazilians Win Trust with Hard Work, Honesty; Committed to Education, Deepening Bond Between Countries

“My great-grandfather went to prison because he loved Japan,” says Caio Aoki on July 3 in Tupa, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

15:28 JST, September 5, 2024

This is the second part of a two-part series on the Brazilian government’s recent decision to apologize for the persecution of Japanese immigrants and their descendants, often referred to as Nikkei or Nikkeijin, during and after World War II.

***

The Brazilian government’s Amnesty Commission made an official apology for the World War II-era persecution of Japanese immigrants and their descendants at its July 25 session.

“I would like to pay homage to your ancestors and respect for their struggle and resistance,” said Enea Almeida, chairperson of the commission.

The history of Japanese Brazilians after World War II in Brazil can be said to have been marked by their struggle against discrimination.

The city of Tupa, with a population of 65,000, is in the interior of the state of Sao Paulo.

It is one of the areas where Japanese immigrants settled in Brazil, with about 500 Nikkei families currently living there.

It is said to be the place where the antagonism started among Japanese immigrants and their descendants, namely between the so-called “winners” who believed a false rumor that Japan had won the war and “losers” who acknowledged Japan had lost the war. The schism divided the Nikkei community in Brazil.

Kanji Aoki, the great-grandfather of Caio Aoki, 33, who became the city’s first Nikkei mayor in 2019, was one of those who after the war was sent to Anchieta Island Prison. The facility is located off the coast of the state and was known as a place where heinous criminals were imprisoned.

Ten years ago, Caio, a fourth-generation Japanese Brazilian who was then a Tupa city assembly member, called for holding a public hearing at the city assembly meeting under the theme of “torture and deaths of Japanese immigrants.”

The response was more than he had expected. About 60 Japanese Brazilians who attended the hearing made various comments, including, “A young man was tortured, kicked and beaten at the police station, and later sent to a jail, where he committed suicide by taking cyanide,” and, “I still want to know why my father was arrested so many times.”

Caio’s grandfather Shunichiro did not speak during the hearing. But during a lunch break, he began talking for the first time about the hardships he endured after his father Kanji was confined in prison. Shunichiro, who was just 11 at the time, had to financially support his family as the eldest son and was pressed to assume such tasks as transporting onions that were harvested.

Caio said the Brazilian government’s official apology will “encourage dialogue among Japanese Brazilians, and between them and other Brazilians, deepening mutual understanding.”

There is an expression that has been passed down in the Nikkei community in Brazil. It goes: “The Portuguese from the former suzerain state built churches while the Japanese built schools.” After World War II, Japanese Brazilians focused on education and worked hard to gain the trust of Brazilian society.

They rushed to reopen Japanese schools that had been closed under orders of the authorities and made efforts to promote learning how to use the abacus and write calligraphy among their descendants.

Roberto Kawasaki, a second-generation Nikkei born and raised in Tupa.

Roberto Kawasaki, 64, a second-generation Nikkei born and raised in Tupa, attended a Japanese language school from the age of 5 as per the plan of his parents, who ran an electrical appliance store.

He recalled, “Education was the only wealth we could build in a place far away from our home country.” He went on to the University of Sao Paulo, considered one of the most competitive universities in Brazil. He now teaches economics at a local technical school.

Japanese Brazilians have noticeably taken professional jobs such as doctors and lawyers. According to a 2017 survey by the government-affiliated Institute for Applied Economic Research, the average number of years of education for citizens with Nikkei surnames was 13.6 years, the longest among the groups of people categorized by eight ethnic roots surveyed. The average hourly wage of Japanese descendants was about twice as much as that of Portuguese and Spanish descendants, the survey found.

In Brazil, the phrase “Japones Garantido” (Japanese are trustworthy) is often used. The image of Nikkeijin as hardworking and honest has taken hold in the country.

“The Japanese community worked very hard here. And today, they are participating in all areas of activities very competently, which is why we are grateful for the help they have provided in building Brazil into what it is today.”

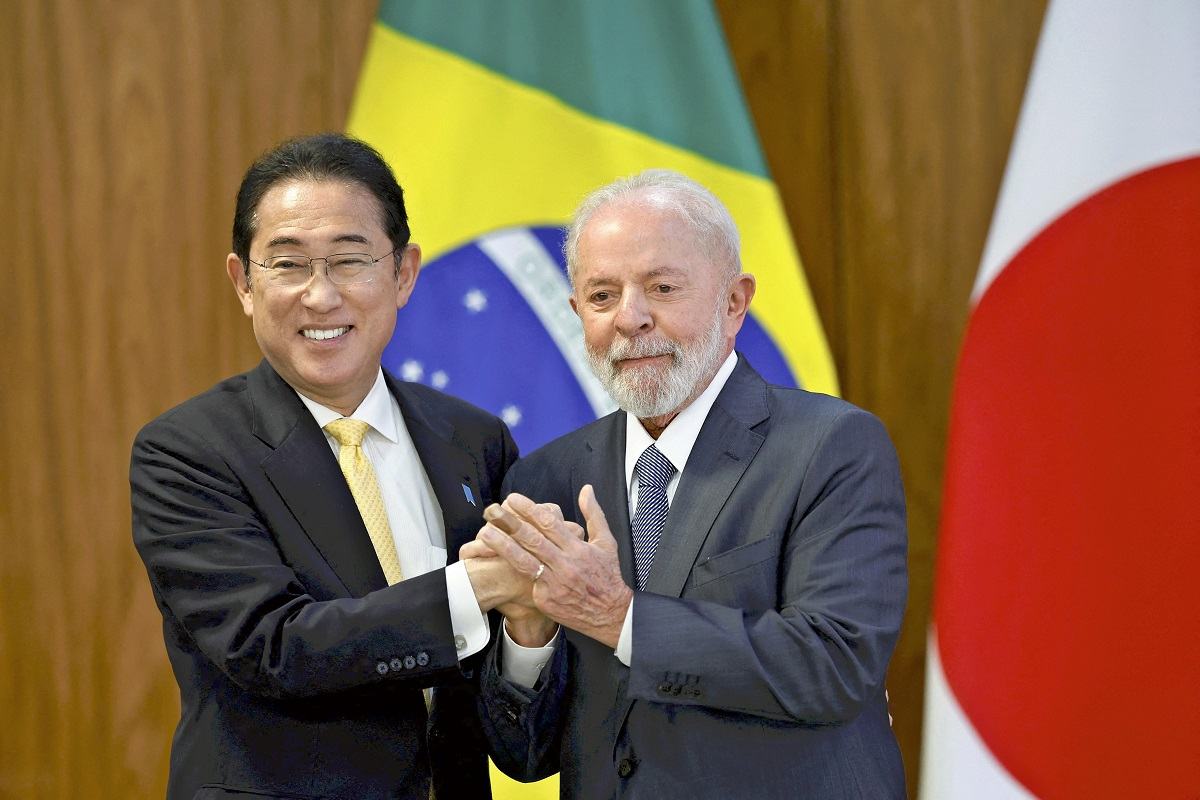

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, on his visit to Brazil, holds hands with Brazilian President Lula da Silva, right, on May 3.

Brazilian President Lula da Silva, 78, made this comment during an interview with Japanese media, that was held before Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited Brazil in May.

He also revealed that he once worked at a laundry run by Nikkeijin in Sao Paulo when he was 12, recalling it as a “good memory of my life.”

Kishida, whose trip to Brazil was the first official visit by a Japanese prime minister in 10 years, referred to the bilateral relations with Brazil at a joint press conference, saying: “The cornerstone is the existence of a special bond created through the Nikkei community. We will cherish this bond and strengthen our cooperative ties.”

Despite suffering persecution in a distant foreign country, Nikkeijin worked hard and became members of Brazilian society. Many of them now feel that the efforts made by them and their ancestors have paid off.

Japanese Brazilians who attended the commission’s session in which the official apology was made rejoiced with tears in their eyes and the national flags of Japan and Brazil in their hands.

Akira Miyagi, 86, a first-generation member of the Brazil Okinawa Kenjinkai, an association of people of Okinawan descent, said, “Our children and grandchildren’s homeland is Brazil. They will strive for the development of Brazilian society, and spread their wings toward the future.”

Top Articles in World

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

North Korea Possibly Launches Ballistic Missile

-

Chinese Embassy in Japan Reiterates Call for Chinese People to Refrain from Traveling to Japan; Call Comes in Wake of ¥400 Mil. Robbery

-

Russia: Visa Required for Visiting Graves in Northern Territories, Lifting of Sanctions Also Necessary

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan