Asia Inside Review: Struggle to Regain Myanmar’s Democracy Supported by People’s ‘Patriotism’

Aung San Suu Kyi and then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton walk together in the garden at Suu Kyi’s house in Yangon in December 2011.

7:00 JST, October 18, 2025

October marks four years and nine months since ordinary Myanmar citizens and ethnic minority forces began a struggle against the military junta to restore democracy to the country.

The citizens’ first experience of a free Myanmar started in 2011 and continued for 10 years during a period of civil rule. The patriotism that was born and developed during this period lies behind the people’s strong solidarity and anger toward the military.

The Myanmar military government will hold elections for both houses of the Union Parliament and local assemblies in December this year and January next year. The government to be inaugurated after the elections will claim legitimacy through having been elected in fair elections in which multiple political parties participated, aiming to win the international community’s approval of the country’s return to civilian rule.

In response, democratic and ethnic minority forces, which have been in armed conflict with the military government since a coup d’etat in February 2021, expressed strong opposition, claiming that the elections are invalid.

In general elections held in 2010 to transition from military to civilian rule, the National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Aung San Suu Kyi, staged a boycott, and the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) won a landslide victory.

The NLD took part in the 2012 by-elections, and Suu Kyi and others became members of parliament. In the 2015 general elections, the NLD defeated the USDP by a large margin, leading to the inauguration of an NLD government, a dream for citizens who had been oppressed by the military regime.

The NLD won an overwhelming victory in the next general elections in 2020, but the military, claiming voting irregularities had occurred, staged a coup and dissolved the NLD. Suu Kyi was detained, and her whereabouts remain unknown.

In the upcoming elections, six national parties, including the USDP, and 51 regional parties will participate. The USDP is highly likely to win a major victory, considering their overwhelming organizational power. Just like in the past, high-ranking military officials will retire from their posts and run in the elections for the USDP.

The Constitution established by the former military regime automatically gives the military 25% of the seats in parliament. Many consider it a matter of course that the new parliament will inaugurate Min Aung Hlaing, the supreme commander of the military, as the new president.

The move would complete the coup d’etat. After that, elections would be used as a tool to maintain the state of military rule under the guise of civilian government. To prevent this from happening, the democratic forces are opposed to holding the elections.

Why did the military launch the coup in the first place? The following is my understanding based on my news gathering activities.

During her first term in power, Suu Kyi initiated the dismantlement of the military government in three ways.

First, she tried to completely eliminate the military from politics. In order to achieve complete civilian control, the NLD submitted a constitutional amendment bill to the parliament, including a proposal to gradually reduce the number of parliamentary seats given to the military. Amending the Constitution requires approval from over 75% of the parliament. The NLD knew that the bill would be rejected by members of parliament from the military, but the move must have annoyed the military.

Second, the military was deprived of its administrative offices, which were put in place by the former military regime in every corner of the country to monitor the citizens. The NLD administration forcibly transferred control of the General Administration Department (GAD), the supervising body, from the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs to the president directly.

The NLD administration also tried to root out corruption from politics. The military controls the economy through two conglomerates that are linked to every industry, from finance to manufacturing to services, and the NLD embarked on an initiative to make the trade of gemstones, which is especially important to the country, more transparent.

As a result of the 2020 elections, the NLD government secured another five-year term. However, the military removed Suu Kyi just before she began her second term, a move that was unforgivable to the people of Myanmar.

Myanmar saw large-scale democracy demonstrations in 1988 and 2007, but its citizens were suppressed by armed military forces. This time, there are 10 major differences compared to the past, as shown in the table.

During the period of civilian rule, many citizens may have for the first time developed a feeling of what could be called patriotism. Before that period, society was dark. A friend of mine in Yangon once told me, “If you talked about politics, even a little, at a bus stop for example, a plainclothes police officer would tap you on the shoulder from behind and take you away.”

When the administration led by former Myanmar President Thein Sein was launched in March 2011, it seemed that the situation would not change at all, and a sense of resignation dominated. Around August the same year, when Suu Kyi and the president reached a compromise, people started to hope for change. In January 2012, when all political prisoners were released, there was a realization that democracy had arrived in the country.

Leaders of student demonstrations in 1988 and other activists to whom the military government had been particularly hostile were all released, and people in front of a prison in Yangon gave a ground-shaking cheer. A young girl wearing an adult-size T-shirt with the phrase “Freedom for ‘prisoners of conscience’” (meaning political prisoners) printed on it was embraced for the first time in her life by her father upon his release.

The prior system of censorship for newspapers and magazines, whose expression had been strictly controlled for nearly half a century, was also abolished. When I was informed of this by a senior official of the Ministry of Information, the censorship authority, I was honestly surprised. I think that giving people freedom of speech was the reform that had the greatest impact on the people. In a society where freedom was ensured, they were able to start actively asserting themselves.

***

Junta intensifies nationwide crackdown ahead of Dec., Jan. elections

The purpose of the latest struggle in Myanmar is not to call for democratization, but for “retaking” democracy. What clearly differs from past struggles is that younger generations, mainly people in their 20s in Generation Z, are taking up arms in collaboration with ethnic minority forces.

A survey conducted by Yangon activists among young people immediately after the coup revealed statements like “We must fight for our country and our future,” reflecting hatred toward the military and the determination to fight.

Many young people evade arrest by security forces and flee to regions controlled by ethnic minorities. There, they receive combat training. A senior member of a group controlling areas near the Thai border, whom I met in July, said:“We have trained over 5,000 young people. They are courageous. They have the spirit that they are willing to sacrifice themselves to improve the country’s future.”

These young people return to their hometowns and join the local units across the nation of the People’s Defense Force (PDF) organized by pro-democracy forces to fight the military.

A shift is also noticeable in the mindset of the people, who for a long time depended on Aung San Suu Kyi. Past democratization movements had spread as the people responded to Suu Kyi’s calls. Now that Suu Kyi is “absent” from the latest democratization move, the people are acting with a strong sense of solidarity, and the struggle appears to be growing more resilient.

However, the military has recently intensified its offensive nationwide to recapture areas lost in the civil war ahead of elections. Pro-democracy media outlets are now reporting that ethnic minority forces and the PDF are at a disadvantage.

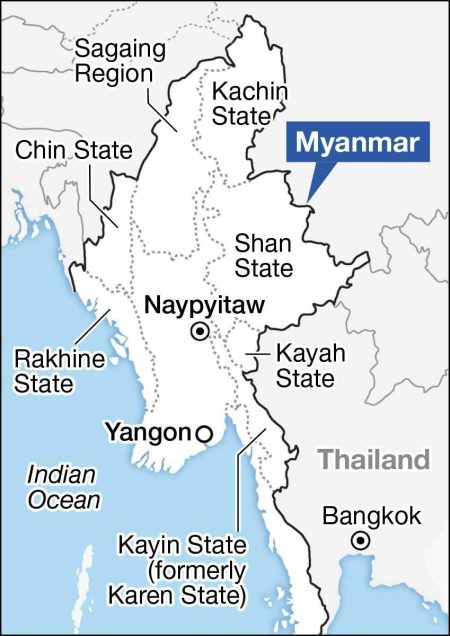

In such states as Shan, Kachin, Kayin (formerly known as Karen) and Kayah, as well as in the Sagaing Region, the military’s airstrikes have become severe, with schools and temples being targeted. According to a Karen National Union (KNU) senior official, suicide drones targeting specific locations have been attacking towns near the Thai border daily.

Pro-democracy elements, including National League for Democracy (NLD) lawmakers, established the National Unity Government (NUG) online immediately after the coup, aiming to unite resistance efforts nationwide. However, criticism has emerged from the public regarding insufficient leadership and inadequate support for local PDF units.

The junta has enacted a new law to impose the death penalty as the maximum punishment for election interference and sabotage activities. According to the Thailand-based human rights group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), 7,328 people have been killed by the military regime or pro-military groups since the coup, as of Oct. 7.

Concerns are growing that military crackdowns will intensify further to force through the elections. The international community must turn its attention to the situation in Myanmar, alongside those in Ukraine and Gaza.

Junichi Fukasawa

Yomiuri Shimbun Director and Senior Writer

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

-

Chronic Issues Erode Thailand’s Economy as Political Confusion Persists, Threatening Terminal Decline in Its Economy

-

Iran Situation: Japan Must Exert Diplomatic Efforts without Merely Standing by

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts