Tadao Ando speaks during an interview at Tadao Ando Architect & Associates in Kita Ward, Osaka.

15:45 JST, April 8, 2021

OSAKA — Internationally renowned architect Tadao Ando, 79, is building a children’s library in Tono, Iwate Prefecture, aiming to create a “cultural renaissance center” for the areas affected by the March 11, 2011, Great East Japan Earthquake.

The library, called Tono Children’s Book Forest, is scheduled to open in July. Ando is in charge of designing and constructing the facility and will donate it to the city upon completion. The library will stock about 12,000 books, including many children’s and picture books.

The Yomiuri Shimbun interviewed Ando about the significance of books and the city of Tono.

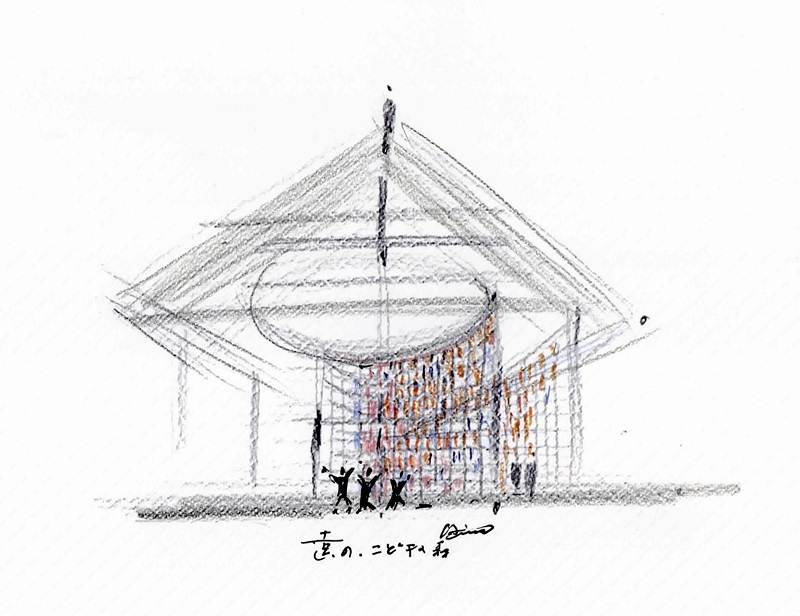

A conceptual sketch of Tono Children’s Book Forest

Focusing on children’s growth

The Yomiuri Shimbun: In the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, you have been behind various efforts to support children in the affected areas.

Tadao Ando: I became a member of the Reconstruction Design Council after the disaster. I visited the Tohoku region with Makoto Iokibe, the council’s chairperson, and Takeshi Umehara, a special adviser.

When I saw the devastated landscapes of the affected areas, I didn’t know whether it would truly be possible to reconstruct these places.

Of course, cities need to grow, but families and children also need to grow. I wanted to provide support for their growth and came up with the idea of setting up an educational fund for children who had lost their parents in the disaster.

I started Momo-Kaki Orphans Fund jointly with Nobel laureates Ryoji Noyori and Masatoshi Koshiba, as well as Tadashi Yanai, chairman and president of Fast Retailing Co., which operates Uniqlo. We raised about ¥5.2 billion by soliciting contributions in units of ¥10,000 annually over a 10-year period. The project ended last year.

I’m grateful for the amount of money that was raised. The project’s secretariat was set up at Tadao Ando Architect & Associates in Osaka, and all contributions were sent to the affected areas. I’m relieved that we were able to send all the money to help children.

Q: What was the inspiration for Tono Children’s Book Forest?

A: We started talking about Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest in Osaka and wondered whether we could do something similar in Tohoku as well.

Q: Why did you choose Tono?

A: When I visited Tono in the past, I was drawn to the world of Kunio Yanagita’s “Tono Monogatari” (The Legends of Tono). I believe that book represents the origin of the Japanese mind.

I want the children who will lead the next generation to cherish that origin story and its world. Through legends of imaginative creatures depicted in the book, such as kappa water imps and zashiki-warashi [a childlike protective spirit believed to bring good fortune to a home], I want children to have broad, strong minds and think about things in a rich manner. I also want them to have pride in their hometowns.

These were all factors [that leads us to Tono].

I’ve heard that Andrew Carnegie, the U.S. steel industry magnate, read many books when he worked as a telegraph messenger boy, and he said the experience had greatly helped him. After retirement, Carnegie used his fortune to build libraries all over the United States and thus contribute to society.

I decided that I wanted to leave behind at least one thing to support children, like Carnegie. So, I came up with the idea of Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, which then led to Tono Children’s Book Forest.

A miniature model of Tono Children’s Book Forest

A world for the mind in Tono

Q: What kind of place do you want the library to be?

A: It is the children who will overcome the tragic situation after the disaster and support the affected areas, and books are the only way to raise bright-eyed and energetic children.

One thing I’m always saying in my lectures and on other occasions is: “You should cut in half the time spent on your smartphone and read books and newspapers instead.”

Our minds can’t develop with smartphones. Children who are readers and thinkers will be the ones who eventually grow up to lead the next generation.

I hope that at least one out of 10 children comes to love books after visiting Tono Children’s Book Forest.

People grow through their own efforts, and books support that process. Parents need to physically support their children, but when it comes to their personal growth, children do so by thinking and accumulating ideas on their own.

I want to create a world for the mind in Tono to aid this growth process in children.

Another important thing we learn from books is that we are not alone. We live together with parents, neighbors, friends, dogs, insects and more on Earth. I think books make us aware that we all coexist on the same planet.

Q: Can you tell us about the design concept, facilities and contents of the library?

A: We’re reconstructing and restoring an old private townhouse in Tono. We felt that reusing a local building would lead to a facility that was unique to Tono.

In the planning stage, finding a suitable structure was a challenge. Then, the Tono municipal government suggested using the former Santaya kimono store’s building.

During the design process, we made efforts to appropriately preserve the original appearance of the building, while at the same time creating an attractive space where books can be easily seen by children, as our focus is on the children.

I plan for the library to be rich in content. It will have a section on the Great East Japan Earthquake. I also hope to present books that famous people I personally know read, such as Nobel Prize winners Shinya Yamanaka and Ryoji Noyori, when they were children.

When architects make these kinds of buildings, they’re virtually an empty box at the beginning. We mostly leave them to their users. It’s essential that the people who use these buildings, including Nakanoshima Children’s Book Forest, contribute to and enrich them.

‘Reconstruction needs hope’

Q: How do you feel about the progress of reconstruction in the affected areas?

A: Reconstruction is difficult. Ironically, rebuilding towns has been progressing, but there are few people there. Many children left the disaster areas with their families.

Shigeatsu Hatakeyama, an oyster farmer in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, said, “If you grow the forest well, the ocean will become rich.” Hatakeyama is involved in the “Mori wa Umi no Koibito” (A forest’s longing for the sea) project, which aims to enrich the ocean by planting trees.

This is the way it should be, but reconstruction projects are going on in a manner that doesn’t connect the forest with the ocean.

I think reconstruction should’ve been done with more human warmth, that is, by considering people’s lives. A lot of money is being spent to build seawalls. But is that all that is needed there? I believe Tohoku’s reconstruction needs “hope” as a remedy rather than money.

Moving forward, it’s important to listen to the people, like Hatakeyama, who have been living and working in those areas. I hope more people carefully listen to the voices of residents and think more deeply about the future of the areas affected by this disaster.

— This interview was conducted by Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer Kodai Fujimoto.

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan