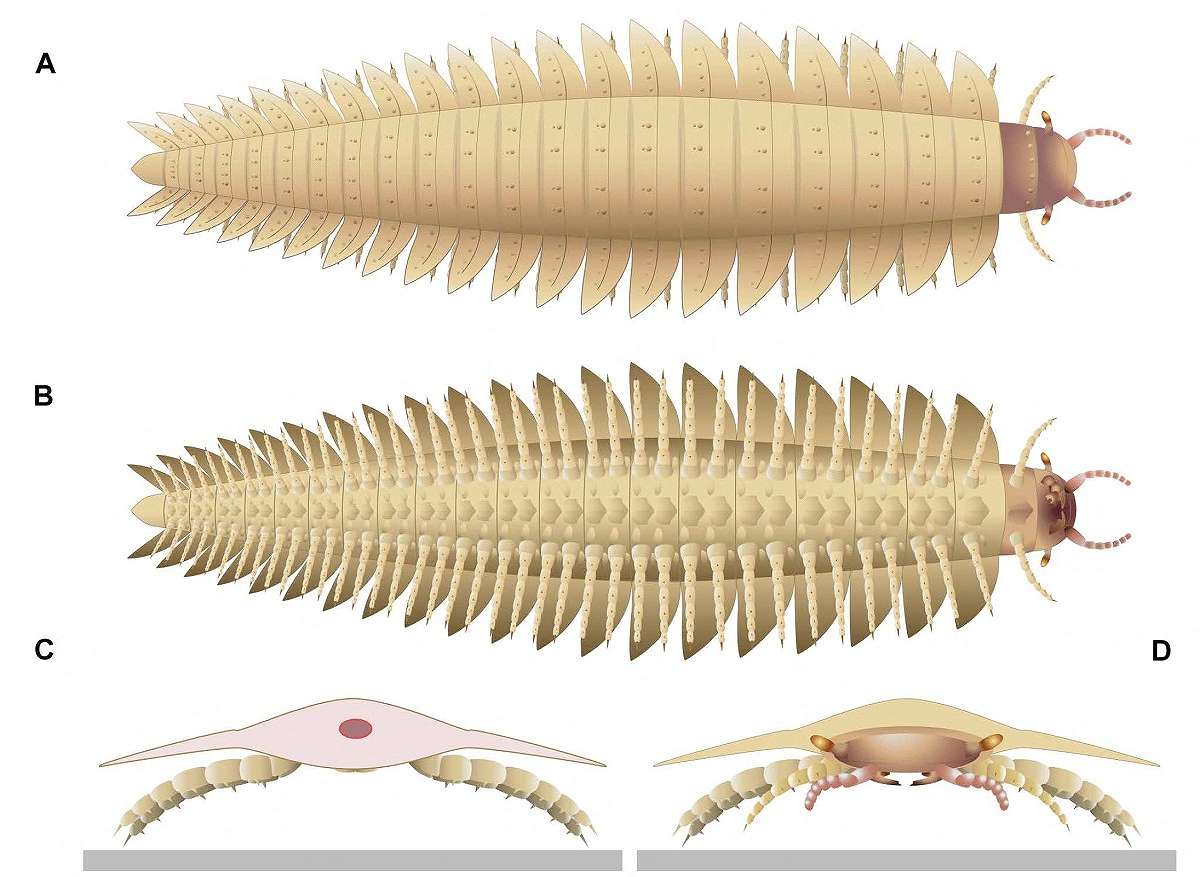

A juvenile Arthropleura is seen in this undated image. A is the dorsal view, B is the ventral view, C is the back view and D is the frontal view.

13:41 JST, October 31, 2024

During the Carboniferous Period, Earth’s atmospheric oxygen levels surged, helping some plants and animals grow to gigantic proportions. One notable example was Arthropleura, the biggest bug ever known at up to 3.2 meters long, inhabiting what is now North America and Europe.

While its fossils have been known since 1854, a large gap has existed in the understanding of this creature because none of the remains had a well-preserved head. The discovery in France of two Arthropleura fossils with intact heads has now remedied this, providing the anatomical details needed for scientists to classify it as a huge primitive millipede and determine it was not a predator but rather a plant eater.

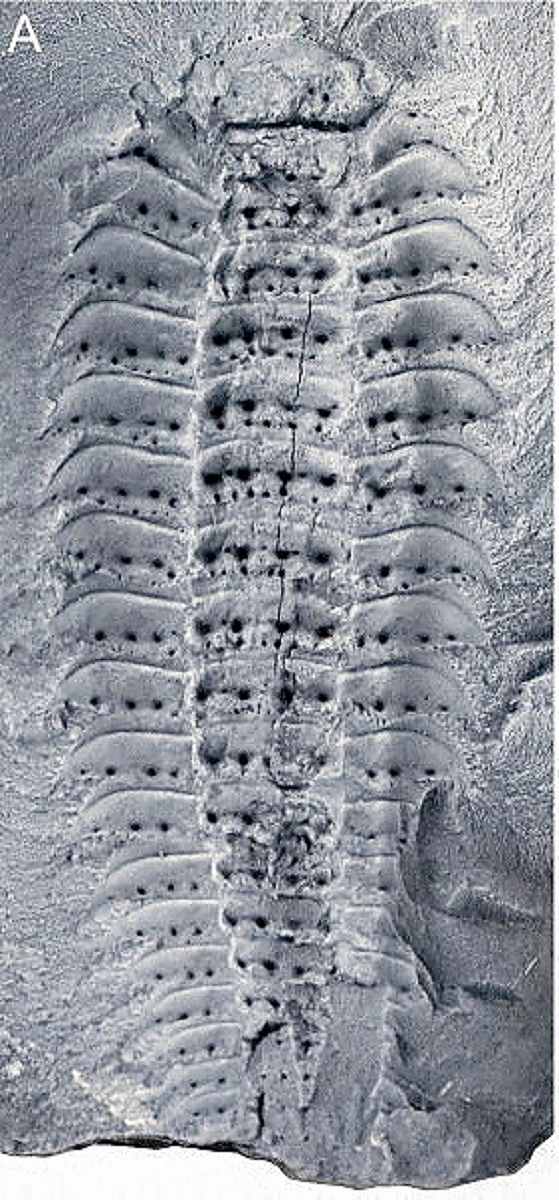

The fossil of a juvenile Arthropleura from Montceau-les-Mines, France, is seen in this undated photo.

The fossils, unearthed in Montceau-les-Mines, are of juvenile individuals, dating to about 305 million years ago. At the time, this locale was near the equator, with a tropical climate and a swampy environment lush with vegetation. While Arthropleura was this ecosystem’s behemoth, the fossils preserve young individuals just 4 centimeters long.

The fossils showed Arthropleura’s head was roughly circular, with slender antennae, stalked eyes and mandibles — jaws — fixed under it. Arthropleura had two sets of feeding appendages, the first short and round, and the second elongated and leg-like.

The specimens each had 24 body segments and 44 pairs of legs — 88 legs in total. Based on its mouthparts and a body built for slow locomotion, the researchers concluded Arthropleura was a detritivore like modern millipedes, feeding on decaying plants, rather than a predator like centipedes.

It could have served the same role in its ecosystem as elephants today or big dinosaurs like the long-necked sauropods in the past — “a big animal spending most of his time eating,” said paleontologist Mickael Lheritier of the Laboratory of Geology of Lyon at Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 in France, lead author of the study published in the journal Science Advances recently.

“I think it is quite a majestic animal. I think its gigantism gives it a peculiar aura, like the aura of whales or elephants,” Lheritier said. “I love to imagine it as the ‘cow’ of the Carboniferous, eating during most of the day — but, of course, a cow with an exoskeleton and many more legs.”

Arthropleura was the largest-known land arthropod, a group spanning the likes of insects, spiders, millipedes, centipedes, lobsters and crabs.

Its head anatomy provided evidence that millipedes and centipedes are more closely related than previously thought.

“These anatomical features are quite striking because even if the body of Arthropleura displays millipede-like characteristics — two pairs of legs by segment — the head characteristics are a mixture of millipede and centipede,” Lheritier said.

Arthropleura’s antennae are millipede-like, with seven segments. The shape of its feeding appendages and position of the jaws are centipede-like, though the shape of the jaws are millipede-like.

The stalked eyes — like a crab’s — are striking because no living members of the group of arthropods that includes millipedes and centipedes — called myriapods — have this kind of eye.

In light of these fossils, the researchers conducted a new analysis combining anatomical and genetic data for centipedes and millipedes, placing Arthropleura as “an ancestral millipede,” Lheritier said.

“Even if it had some centipede mouthparts, its trunk anatomy seems to indicate that it was not carnivorous like modern centipedes, as it did not have forcipules — centipede ‘fangs’ — or any appendages built for hunting. Having two pairs of legs by segments, like millipedes, affected its locomotion and implies it was a rather slow arthropod,” Lheritier said.

Other examples of Carboniferous arthropod gigantism included Meganeura, an eagle-sized dragonfly, and Pulmonoscorpius, a scorpion more than 1 meter long.

“There are two possible factors to explain this: a peak of oxygen concentration in the atmosphere during the Carboniferous and the availability of resources. As arthropods colonized land before vertebrates, they had access to new resources that favored their diversification, and some species could gain gigantic sizes,” Lheritier said.

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

-

iPS Cell Products for Parkinson’s, Heart Disease OK’d for Commercialization by Japan Health Ministry Panel

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan