A microhydropower generation facility installed in the Suisha-Shinden district of Nada Ward, Kobe

22:10 JST, January 26, 2022

KOBE — Electricity is being generated by microhydropower in Nada Ward, Kobe, using the rapid current from a river flowing down the Rokko mountain range. Power generated by waterwheels set in rivers was once used to polish rice, contributing to the development of the sake industry in the area. Generating electricity via microhydropower in an urban area is said to be rare, and a modern version of the waterwheel is garnering attention.

Electricity for 30 households

The Suisha-Shinden district is about 1.5 kilometers north of Hankyu Railway’s Rokko Station. The Rokko River, which is administered by the Kobe municipal government and the Hyogo prefectural government, runs through a residential area there. A 1.8-meter-high power generator installed near the river began operating in April last year.

Water pipes were laid from near a waterfall about 300 meters upstream to operate the power generator using an altitude difference of about 30 meters. The electricity generated can power about 30 households, and a local cooperative buys and sells the electricity.

The microhydropower facility was set up by a local nonprofit organization, PV-Net Hyogo Global Service, which works to spread the use of renewable energy. The installation cost of about ¥65 million was covered by the prefecture’s interest-free loan program and other sources.

Water intake from the river, pipe installation, power generation and other processes require going through procedures such as obtaining permission from the river administrators. Completing all the necessary procedures, including submitting the application and providing explanations to local residents, took about 10 years.

Hydropower history

Ryuichi Kitakata, 85, who heads the NPO, came up with the idea of using microhydropower because local industry had been supported by waterwheels in the past. According to “Kobe-shi Shi” (The history of Kobe), waterwheels were built in the Nada area, including the Suisha-Shinden district, along rivers running from the Rokko mountain range since the middle of the Edo period (1603-1867), with at least 129 waterwheels in operation in 1838.

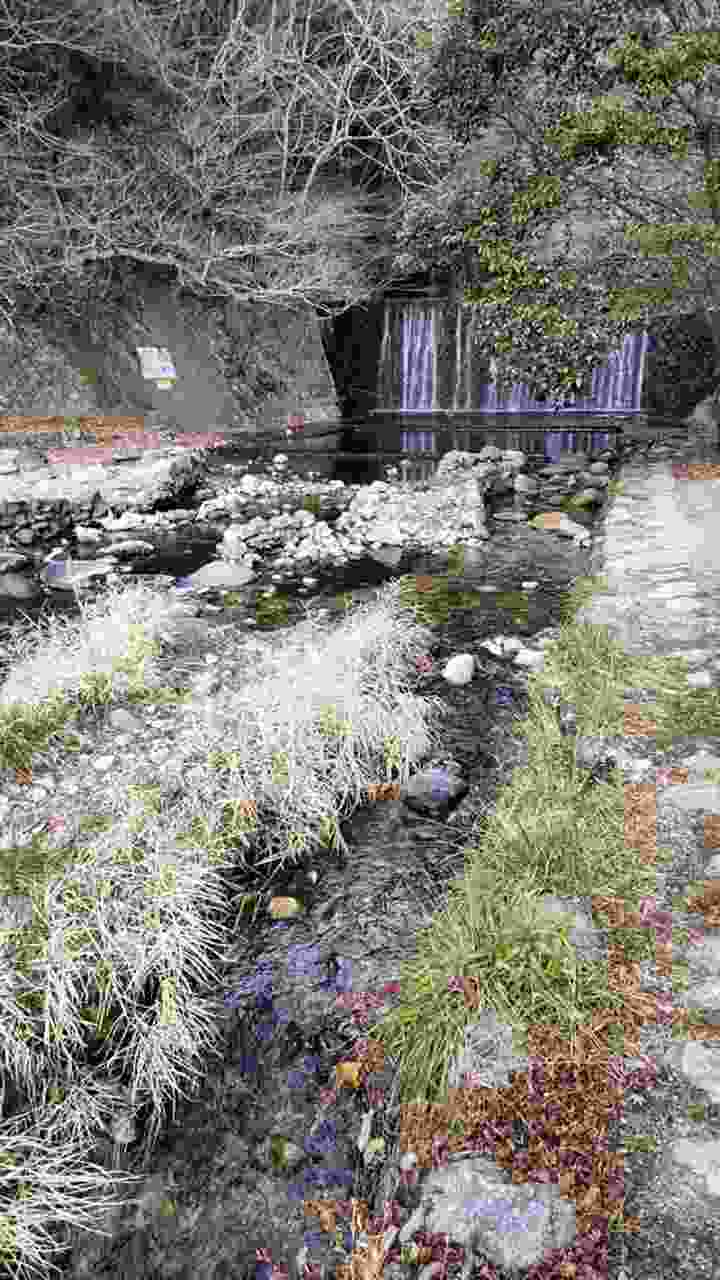

Near the water intake point on the Rokko River in Nada Ward, Kobe

Many of the waterwheels were used to polish rice for sake, especially in the final years of the Edo period. Using waterwheels dramatically improved quality and efficiency compared to pedal-operated rice mills, which were mainly used at the time. As a result, high-quality sake could be mass-produced and the area became one of Japan’s largest sake production bases.

With the creation and expansion of electric power grids from the late Taisho era (1912-1926) to the early Showa era (1926-1989), the use of waterwheels waned, and most of them were washed away in the 1938 Hanshin flood, which killed more than 600 people.

The remaining waterwheels were designated by the central government as an important tangible folk-cultural property in 2000 as equipment related to the sake brewing process in the Nada district. However, few local residents know about the history of the waterwheels.

Because the forest where the pipes were laid was left unattended, the NPO took control of it. The NPO is considering starting activities to preserve satoyama, or community forests, together with students from nearby Kobe University.

“I hope this place will provide opportunities for young people to learn about the wisdom of our predecessors and become interested in the environment and renewable energy,” Kitakata said.

Local production, consumption

Various places around the country are taking advantage of regional characteristics for locally producing and consuming electricity.

The Kiyokawadashi wind, which blows in Shonai, Yamagata Prefecture, is known for being one of Japan’s three wildest winds. The town of Shonai built large windmills in 2002. In fiscal 2020, the town reportedly earned revenue of about ¥50 million from selling electricity produced by the windmills.

In Asago, Hyogo Prefecture, where forests make up about 80% of the city area, the prefectural government, a local forestry association and others started operating in late 2016 a biomass power plant that uses timber from forest thinning and other materials as fuel. The facility generates enough electricity for 12,000 households.

According to the Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry, there were 903 microhydropower facilities using the government’s feed-in tariff system across the country as of the end of June 2021, compared to 3,514,799 solar power plants and 2,081 wind power plants. Because of the many licensing and other procedures, widespread adoption of hydropower is taking time.

“There are many rapids in Japan, so I’m sure microhydropower generation will be utilized more in the future,” said Masaru Nakajima, secretary general of a Tokyo-based private organization that promotes microhydropower use across Japan.

"Science & Nature" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

‘Fiercest, Most Damaging Invasive Weed’ Spreading in Rivers, Lakes in Japan, Alligator Weed Found in Numerous Locations

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

Japan Set to Participate in EU’s R&D Framework, Aims to Boost Cooperation in Tech, Energy

-

Tsunami Can Travel Vast Distances Before Striking, Warn Japanese Researchers

-

Japan’s H3 Rocket Failed in Latest Launch, Says Official

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

BOJ Gov. Ueda: Highly Likely Mechanism for Rising Wages, Prices Will Be Maintained

-

Core Inflation in Tokyo Slows in December but Stays above BOJ Target

-

Osaka-Kansai Expo’s Economic Impact Estimated at ¥3.6 Trillion, Takes Actual Visitor Numbers into Account

-

Japan Govt Adopts Measures to Curb Mega Solar Power Plant Projects Amid Environmental Concerns

-

Major Japan Firms’ Average Winter Bonus Tops ¥1 Mil.