Culinary Workers Union Local 226 members Elsa Roldan and Alma Lozoya speak to a Nevada voter as they canvass tough residential neighborhoods in Las Vegas last month.

15:32 JST, October 26, 2022

This is the state of play in the final weeks of Election 2022 as Democrats and Republicans compete for the votes of Latinos in battleground Nevada. The scene is reminiscent of the trench warfare playing out in swing-state neighborhoods across the country. In no recent election have the votes of Latinos been so closely monitored or perhaps so fiercely fought over.

***

LAS VEGAS – The midday sun beats down on Elsa Roldan and Alma Lozoya as they begin another day of canvassing in a predominantly Latino neighborhood of stucco homes with tile roofs and rocks for landscaping.

Roldan, 61, is a housekeeper at the Bellagio hotel and casino, a job she’s held for 14 years. Lozoya, 33, is employed as a porter at Caesars Palace after losing her job at another casino early in the pandemic. They are on leave from their jobs, now being paid by the Culinary Workers Union, Local 226, to go door-to-door mobilizing voters ahead of the November elections.

The neighborhood is a mix of homeowners and renters, many of whom have experienced rent increases. At the first four homes they knock on, no one answers. At the fifth, a man opens the door but is not receptive to their appeals. At the sixth, a woman appears at the door. Roldan and Lozoya offer campaign fliers and ask whether the woman would also sign a statement calling for rent stabilization regulations. “Is this a Democratic issue?” the woman responds. “I’m a Republican. No, thanks.”

At the next six houses, there is no response. Then, at the seventh, a young man answers the door. “I usually vote late,” he says, meaning on Election Day, Nov. 8. Roldan and Lozoya are buoyed by the response. They turn around and keep canvassing. At yet another house, a young woman answers the door. She says she is on the phone with her boss and in a hurry. She said her rent has increased, takes their literature and reassures them she will be with them in November. “I’ll vote,” she says before closing the door.

By the end of a typical shift, Roldan and Lozoya will have knocked on roughly 120 doors, but rarely does an interaction translate into immediate, hard-and-fast support, which keeps open the questions of just who will show up to vote and for whom.

Here in Nevada, Democrats are worried about losing the Senate seat held by Catherine Cortez Masto, a Latina completing her first term. She and former state attorney general Adam Laxalt (R) are in a toss-up contest. A Laxalt victory could tip the Senate to GOP control. Democrats are also nervous about the governor’s race, which pits Democratic incumbent Steve Sisolak against Republican Joe Lombardo, the sheriff of Clark County, which encompasses Las Vegas. In addition, three House seats currently held by Democrats are seen as competitive.

The Latino electorate nationally is made up of diverse communities, shaped by different backgrounds and motivated by divergent issues in each region. Beyond Nevada, Latino turnout next month – and the margins by which these voters split their support between Democrats and Republicans – will help to decide the outcome of Senate, House and governors’ races in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, New Mexico, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Texas.

In Nevada, Democrats have depended on the votes of Latinos in closely fought elections. In 2016, they favored Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by 60 percent to 29 percent, helping Clinton win the state by two percentage points overall, according to exit polls. In 2020, that margin shrank to 61 percent to 35 percent, as Joe Biden also won by two points.

This year Democrats in Nevada are especially worried, both about their margins and assuring a hefty turnout among Latino voters sympathetic to their candidates. They say the current political climate is as challenging as they have seen it in years. Economic issues are paramount. Nevada has struggled to rebound fully from massive job losses in the hospitality industry triggered by pandemic shutdowns, and now high prices for gasoline, groceries and housing are being felt acutely among Latinos and others.

“We’re going to have to knock on more doors than we’ve ever knocked on ever and we’re going to have to talk to more people,” said Ted Pappageorge, 61, secretary-treasurer of Local 226. “If we’re not out there, I’m just going to say this, then we think Democrats lose – and they lose in Nevada and they’ll lose in Arizona and they’ll lose in Pennsylvania.”

Latinos are one of several groups whose votes will be pivotal this November as Democrats seek to reassemble their past winning coalition to avoid major losses. Other groups include White women, both those with college degrees (who have trended Democratic) and those without (who have trended Republican). Black voters, both men and women; and voters under age 45. They all can be called “the deciders,” the focus of a Washington Post series this fall.

Four years ago, when Democrats captured the House, about 2 in 3 Latinos supported Democratic candidates. Democrats appear to be struggling this fall to replicate both that margin and the size of Latino turnout.

In 2020, Democrats saw their traditionally hefty margins among Latinos sag nationally. More significant shifts came in South Texas and South Florida, for different reasons, but which together have generated debate about whether this was a hiccup to an otherwise steady pattern of Democratic dominance or evidence of a broader change in which Latino voters become a genuinely contested constituency. Success by the GOP next month and beyond, even if it falls short of winning a majority of Latino voters, would upend many assumptions about future elections.

Republicans have intensified decades-long efforts to lure more Latino voters to their side. In 2020, the Trump campaign targeted potentially receptive Latino voters, especially in South Florida, labeling Democrats as socialists and claiming the Democratic Party supports open borders. Republican appeals go beyond attack politics, for example by playing to the interests of Latino small-business owners based on economic philosophy.

For Democrats, knocking doors has historically been a key weapon in mobilizing Latino voters. In addition to the Culinary Workers, other pro-Democratic groups are canvassing in Nevada, from what remains of the powerful political machine built by Sen. Harry Reid under the name Nevada Democratic Victory to several Latino-focused political operations. The question this fall is whether the canvassing will drive high enough turnout among Democratic sympathizers to overcome worries about inflation and other concerns.

That leaves much in the hands of workers like Roldan and Lozoya. Laboring under the broiling sun, they wait in vestibules that are often the only shade they can find. The work is tiring and often frustrating.

The hardest part, Roldan said, is the heat, which reached triple digits during the height of the summer. The heat, she said, “and the dogs,” which can be a frightening presence at people’s doors. Despite the physical hardship, the women say the work is as rewarding as it is valuable. “I feel very satisfied,” Roldan said, “because I never thought this would fulfill my soul, my spirit.”

Roldan said the election is important because, “if we don’t go Democratic, we are at risk to lose our rights, things we have been fighting for, for a long, long time,” specifically noting abortion rights. “In the blink of an eye, things can turn different.”

Elsa Roldan and Alma Lozoya walk through a residential neighborhood in Las Vegas.

The wake-up call

Latinos are the largest minority group in the country and make up nearly a fifth of the U.S. population. That includes those who are not citizens. The Latino population is roughly triple the size of the Asian American community and about 50 percent larger than the Black population. Among those who are 18 or older and eligible to vote, Latinos now slightly outnumber Black Americans, but they vote in lower numbers and therefore account for a slightly smaller share of the electorate than Black voters.

All this makes Latinos one of the most important constituencies in American politics. But the Latino vote defies easy categorization or simple description because it is demographically and geographically diverse. What might appeal to Latinos in one part of the country does not work in another. What motivates Cuban Americans – for years it was staunch anticommunism – does not necessarily win over Mexican Americans.

In California, Texas and states across the Southwest, Mexican Americans dominate the Latino population. Florida is a mix of Cuban Americans, Puerto Ricans and, increasingly, immigrants from South American countries like Venezuela. In the past, Mexican Americans in Texas were more receptive to Republican appeals than those in California, in part due to the age of the population and the period of time families had been in the United States.

As with many voters overall, Latinos are especially sensitive to economic conditions, and in Nevada this fall that puts an obstacle in the path of the Democrats. Economic issues are paramount due to the combination of the rising costs for essentials like food, gasoline and housing and the aftereffects of pandemic shutdowns that hit Latino families especially hard. Other issues are in the mix, including abortion, but Democrats say the battle here is being waged on an economic landscape.

Culinary Workers Union Local 226 organizers Gisela Flores and Mirian Cervantes

Mirian Cervantes, who is part of the Culinary Workers union organizing team, underscored how critical every vote could be in November, given how tight the polls show the race for the Senate here. “You don’t want to lose any door,” she said.

Some Democrats have assumed that Latino voters can be swayed on the issue of immigration, but that is not always the case. On that issue, these voters have varying views. More than 8 in 10 back a path to citizenship for those who are in the United States without legal documentation, while 6 in 10 say they support more funding for border security, according to a recent Washington Post-Ipsos poll of Latinos. When asked which party they trust to deal with immigration, 38 percent say Democrats, 31 percent say Republicans and 30 percent say neither.

Republicans long have argued that their party is a natural home for many Latino voters, based on values of patriotism, family, community and faith. But only in a few cases were they able to win even a significant minority of those votes in presidential elections. The best performance came in 2004, when President George W. Bush won at least 40 percent of the Hispanic vote nationally, according to an analysis by the Pew Research Center.

Bush’s success was attributed to his long cultivation of Hispanic voters when he served as governor of Texas. The GOP’s 2008 and 2012 nominees, John McCain and Mitt Romney, respectively, fell short of his performance. In 2016, Democrats saw in Trump an immigrant-bashing candidate who they believed could repel some of the Latino voters who had been voting Republican. Instead, Trump did about as well with Latinos as Romney in 2012, winning just under 30 percent of the vote.

Then came 2020 and the wake-up call. Amid a surge in turnout in the Latino community, President Trump’s share of the Latino vote jumped 10 percentage points, to 38 percent, according to a Pew Research analysis of voters. Other sources put the decline in the Democratic share between three and eight percentage points, depending on the source of the data.

In Nevada, Biden won the state over Trump by about 34,000 votes. Had Latino support for the Democratic ticket remained stable from 2016, he would have won by about 55,000 votes, according to a post-election analysis by Catalist, a Democratic data firm.

In South Texas, which has a large Latino population, GOP gains were especially striking. Trump won 47 percent of the vote in relatively small Starr County, up from 19 percent in 2016. In more populous Hidalgo County, the Democrats’ margin fell from 40 points in 2016 to 19 points in 2020.

Texas could be undergoing a true realignment, said Carlos Odio, co-founder and senior vice president at Equis Research. But an Equis report in late September noted that if Republicans want to claim a broader realignment, they will need to first demonstrate consistent gains in Nevada and Arizona.

The shifts in Florida in 2020 were undoubtedly significant, but analysts warn against extrapolating what happened there to the rest of the country because of the unique makeup of the Latino population there. But the shifts there, unless Democrats can reverse them, make the state more fertile ground for the GOP.

The 2020 results brought a new focus to the debate about whether the Latino vote is becoming much more of a swing vote than one solidly Democratic. Patrick Ruffini, a Republican pollster, said he believes that over time Latino voters could follow a pattern resembling that of some European immigrants from the last century. Those groups began as more staunchly Democratic but as they became more assimilated increasingly split their votes between the two parties.

“I think this is really part of a long arc of Hispanics kind of following in the footsteps of other immigrant groups that we’ve seen in the past,” he said. “Over generations, they start blending in.”

David Leal, a professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin, said Democrats may have been lulled into assuming that the burgeoning Latino population would forever accrue to their benefit politically.

“I think that there is this idea in many Democratic circles about how demography is destiny and demographic change is going to produce this electoral dividend,” he said. “It’s becoming a little more clear that this story is much more complicated than that.”

The GOP’s appeal

For some Latinos, the Republican Party has long been a comfortable home. Conversations with two Republican-leaning Latinas in Nevada offer insights into why.

Iris Ramos Jones, 37, came to the United States from Ecuador, nine years ago. Married and the mother of a young daughter, she works as a Realtor, is registered as a Republican and fears that the Democrats are taking the country in a socialist direction.

Educational choice advocate Valeria Gurr

Valeria Gurr, 39, emigrated from Chile more than a decade ago. Married with a young son, she is active in the school choice movement through Federation for Children. She was once registered as a Democrat, switched to independent and now is a registered Republican. But she has no strong tie to either party; she said she votes on issues.

Jones embodies the story of many immigrants who have come to the United States over generations. When she arrived, she found herself in rural West Virginia, with only rudimentary English. She later moved with her then-husband, the father of her daughter, to Las Vegas, then went through a divorce, at which point she had no family to fall back on. With the encouragement of the man who would become her current husband, she decided to pursue the real estate business. Her husband works as a political consultant.

“I am living the American Dream,” she said. “I want my kid to understand that she must respect this country. . . . She needs to respect everybody. She doesn’t have to agree or copy other people. Just respect everybody.”

Realtor Iris Ramos Jones

Jones’s identification with the Republicans, she said, is based on values. “There are good things about both parties, but my personal values are more aligned with them. Family. Freedom. Hard work. I don’t need and I do not appreciate the government telling my kids what they should believe or not,” she said.

Jones said Republicans are working harder to attract support from Latinos and sees the economy as an issue that could accelerate a shift. “Every time you go to the grocery store, you feel there has been a change,” she said. “Now every time you get gas, there has been a change.”

She worries about the direction of the country if Democrats remain in charge. “My country had been destroyed [by socialism],” Jones said, referring to her native Ecuador. “I know what socialism looks like. And it is very unfortunate that this is the path we are going in this country right now,” she said. “. . . I didn’t come here and sacrifice so much just for my child to have to live in the same type of country that I was born in.”

Gurr, meanwhile, is mostly a single-issue voter. For her, education is the key to almost everything and she believes Democrats have not paid enough attention to the needs of those in the Latino community. “I think Hispanics come to this country because . . . we see so much opportunity,” she said. “If you work hard and you try hard, you’re able to make it. But the promise of the American Dream, in my opinion, is broken without access to a quality education.”

Gurr said her mother was one of nine children and struggled to build a better life in Chile. “I came to the United States of America thinking only this is the greatest country in the world when it comes to education, but I realized that the education system was not different than in Chile,” she said. “And essentially, my community was left behind.”

She has lost faith in Democrats. “They basically told me that if they are supportive [of school choice], they cannot put their face to it because it will mean that they will lose their seat,” she said. “I basically realized it was about politics and not about kids. It was like a growing-up moment. It was like, ‘Oh, I’ve been very naive to think it’s about the kids.'”

To Gurr, the Republicans are far from perfect. “But I will say the Republicans have been more open here in this particular state to reach out to me and say, ‘Hey, Valeria, what do you think? How do we fix this?'”

She said she has voted “for all sides of the [political] spectrum” but will vote Republican in November. Does she see Latino voters as being more up for grabs? “I can only speak about me,” she said. “I know I am, for sure.”

This fall, she will vote Republican for both the Senate and governor.

Peter Guzmanis president and CEO of the Latin Chamber of Commerce in Las Vegas. What he sees is a Latino community still feeling the effects of the pandemic and thinking about its political options. “They are pausing, reflecting and paying attention,” he said.

He said that many Latino parents in Las Vegas are still upset over school closures. “I call them the Latino soccer moms,” he said. “They are pissed. They’ve been going along with the status quo for a long time, and now, you know, they saw their kids get left behind and struggling to find internet and struggling to keep up.”

Guzman also pointed to the impact of inflation on many of the small businesses that are part of his organization. He cited as an example a landscaper with half a dozen trucks and crews paying more for gasoline. “When you have a grown man sitting [here] with tears in his eyes saying, ‘My business was going so well, and these gas prices are driving me out of business,’ that’s powerful, man,” he said.

Democrats know they are in a battle for the allegiance of Latino voters. Several said they have seen no real deterioration in Latino support for Democrats since 2020 but acknowledge that the environment remains unstable and could lead to more gains by the GOP. They are looking especially closely at Nevada and Arizona this fall. What also worries some strategists is whether Latino voters will turn out in the numbers needed for victory.

“I read a lot about the narrative that Latino voters are shifting,” said Melissa Morales, founder and president of Somos Votantes, a national Latino advocacy group. “I certainly heard that on the doors in 2020. We’re not hearing that on the doors as much this year. I’m more concerned that our base stays home, that they simply don’t vote.”

Are Democrats losing ground or gaining votes?

The shifts among Latinos nationally and especially in places like South Texas and South Florida have touched off a debate about the trade-off between the possibility of smaller Democratic margins in future elections and the continued growth in the numbers of Latinos now voting, particularly in states where they represent a substantial share of the population.

“Nationally, Democrats lost a couple percentage points [in 2020], but they gained more votes,” said Matt Barreto, a pollster who was part of Biden’s 2020 team and, among other responsibilities, works with Building Back Together, which is trying to advance the Biden agenda. “Biden would not have won Arizona or Nevada without the huge increase in Hispanic turnout.”

Potentially offsetting the problems in South Texas, Barreto said, is the continuing gains Democrats have made with Latinos and other voters in the major cities of Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio, which he said have produced far more net votes than were lost in South Texas.

The Democrats’ gains in the Texas cities – which have been among more than just Latino voters – reduced the GOP’s statewide winning margin in presidential races from 16 percentage points in 2012 to six in 2020.

Barreto also echoed what others pointed to: the possibility that 2020 reflected more about Trump and less about appeal of the Republican brand. “Hispanics were hit extremely hard by covid, both health and economic,” he said. “And so, if there’s a . . . net boost [for Democrats], it seemed like it was a Trump effect and not necessarily a Republican effect.”

Simon Rosenberg, president of the New Democrat Network, has been focused on the Latino vote for two decades, particularly in the Southwest. He calls what has happened over that period a major success story for Democrats. In 2004, he said, by his calculations, Democrats netted about 700,000 Latino votes. By 2020, that had grown to between 4 million and 5 million. In 2004, Bush won Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada and Arizona. In 2020, Biden won all four.

Rosenberg also noted that, nationwide, the Pew study of the 2020 vote showed Democrats with a 21-point margin, 59-38 percent, among Latinos, while a recent Pew survey showed that Latino registered voters favor Democrats by 53 percent to 28 percent, a 25-point margin, for November. “Erosion is the wrong word to associate with what we’re talking about,” he said.

But Ruy Teixeira, who has been studying population and voting trends for years and is now at the American Enterprise Institute, said Democrats should be worried by the falloff in Latino support in 2020.

“It’s just remarkable how widespread it was and how pervasive and how geographically diffuse,” he said. “Certainly it has something to do with Trump, but I think it is broader than that. It has to do with how the Democrats themselves have evolved.” He said Democrats have moved “very noticeably” to the left, leaving them far away from the median voter in the country. “I think for the median Hispanic voter, that distance is even farther,” he said.

Odio of Equis Research turned the question of 2020 around. “Many people ask, why did people move toward Trump in 2020? And I think the better question is, why had they held back from Trump at ’16 or for Republicans before that?” he said.

His reasoning is that given various aspects of the makeup of Latinos – religious, working-class, striving – it would not be surprising to see them as open to voting for a more conservative candidate or party. He also said that economic issues could have become more important by 2020 and, with Latino incomes continuing to rise (and faster than among other groups), more of these voters decided to go with Trump rather than Biden.

The other factor was the impact of the pandemic and business closings. In Nevada, Latinos were especially hard-hit when the casinos shut down and tourism evaporated. Democrats were identified with those closures. “If an election was to be a referendum on immigration, Democrats would do better among Latinos,” Odio said. “If it were to be a referendum on the economy, they would do worse, and it was closer to a referendum on the economy.”

Nevada could prove a test case in the debate over rising participation by Latinos vs. Republican inroads. Can Democrats through their mobilization efforts turn out Latinos in numbers big enough to hold the Senate seat that could tip the balance of power in that chamber?

Trying to connect

On a recent evening last month, about two dozen people gathered for food and phone banking on behalf of Cortez Masto at a strip mall east of downtown Las Vegas. After a training session, volunteers were given lists with dozens of names of potential voters and they began punching numbers into their cellphones.

Amie Martinez, 21, a college student, said she has been attending political rallies with her family since she was much younger but was doing this work for the first time and was there to encourage younger Latinos like herself to vote this fall.

“I consider myself a Democrat because they’ve always been there for the Latino community,” she said. “And they always fight for our rights, and they want the best for us.”

A few seats away, Carlos Velis, 75, looked down at his mostly blank sheet of paper. “I dialed and somebody answered, but they didn’t say anything and pretended they weren’t listening,” he lamented. He added with a laugh, “What can we do?”

The work that night was one part of how the individual campaigns are trying to reach Latino voters. Cortez Masto started Spanish-language advertising in March, focusing on her personal story and that of her family. Her campaign has spent more than $3 million on Spanish-language TV, radio and digital advertising and direct mail, according to communications director Josh Marcus-Blank.

Laxalt’s campaign officials say they started to assemble a coalition of Latino support even before the Republican primary. The Laxalt campaign has invested more than a million dollars in its Spanish-language TV, radio, digital and mail, according to campaign adviser John Ashbrook.

In conjunction with the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the Laxalt campaign is also contacting voters directly, focusing on independents and those identified as loosely tied to the Democratic Party. “We have a great opportunity to flip them over,” said Jesus Marquez, senior adviser and Hispanic engagement director for the campaign.

An army of canvassers

Scholars who have specialized in studying Latino politics and voting patterns say direct contact between campaigns and voters is the most effective form of communication and the likeliest path to increasing turnout.

“When you reach out to the Latino voters, when you actually contact them, when you talk about the things that they care about . . . in ways that make sense to them and that actually relate to their day-to-day lives, they will turn out to vote,” said Lisa García Bedolla, vice provost at the University of California at Berkeley.

That makes the coming election a new test case, given that Democrats did very little canvassing around the country two years ago because of the pandemic. For example, Sophia Jordán Wallace, a political science professor at the University of Washington, said she has been hesitant to generalize about changes in the Latino vote because 2020 was a difficult year for traditional mobilizing strategies.

“We were still operating at a time in which Democrats weren’t doing as much get-out-the-vote effort in terms of in-person [contact],” she said. “. . . I think we will know the answer to whether the outreach theory is correct when we see what happens in this election, when in theory Democrats have been doing their normal thing.”

That puts more pressure than ever on the organizers knocking doors daily in places like Las Vegas. But who are they? What motivates them? And what are they seeing?

On a recent afternoon, Cervantes and a colleague who goes by the name of Rocha M are gathered around a conference table at the Culinary Workers union offices. Like Roldan and Lozoya, they are part of an army of more than 350 canvassers the union is deploying to knock doors.

Culinary Workers Union Local 226 member Rocha M

Rocha, 42, was born in Mexico, immigrated to Texas when she was 23 and eventually made her way to Las Vegas. Her goal is to keep Nevada in the Democrats’ column. “We have to teach our community that our vote is really important,” she said.

She spoke about the overt racism she felt while Trump was in the White House. “It was for me more hate on the streets,” she said. “I’m not saying he’s all of the Republicans, but I’m saying at that time it was really, really bad . . . like we were sometimes scared of going out because, well, I do look Mexican, you know, I cannot hide it.”

She has “passion in my veins” as she goes door-to-door, calling the work she is doing the best experience she has had with the union. “I do the push because one door, it can make a difference, one-on-one conversation and it can make a difference. I never feel like, oh, this is too much.”

Cervantes, 49, was born in Arizona, later moved to Mexico and eventually returned to the United States. She, too, felt the sting of racism during Trump’s presidency. “I felt attacked,” she said. “I’m not a drug dealer. I do housekeeping. My husband, . . . he’s not, like, abusing people. He works in construction. But you know [Trump] was so racist. You can feel [it] going to any restaurant. . . . It was a really, really bad situation back then.”

Like Rocha, Cervantes said she is driven to work the long hours she is spending in the neighborhoods. “I know it’s hot. I know I had to use sunblock like three or four of five times a day. . . . I come out so red on my face. But it’s one of those things, like, you love to do it.”

Victor Villanueva speaks about the upcoming election.

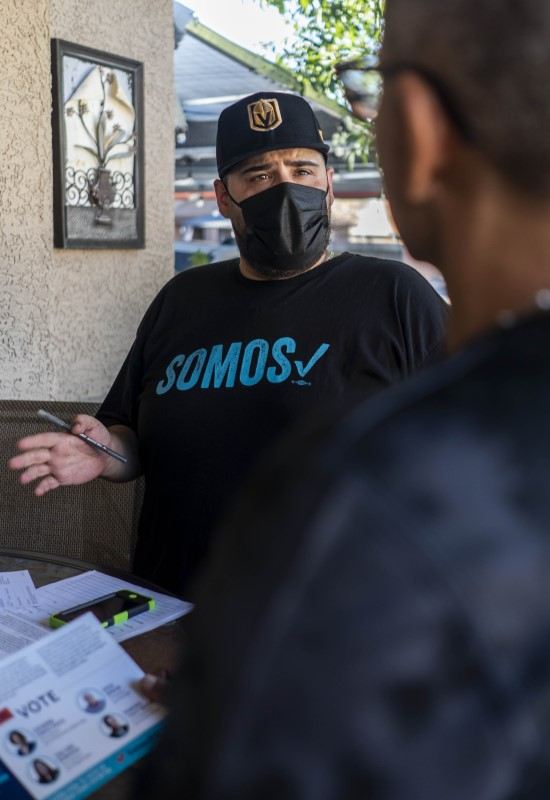

Victor Villanueva, 32, is canvassing for Somos Votantes. Born in Aurora, Ill., to parents who came to the United States from Mexico, he lived there until he lost his job during the pandemic. When he heard about the work Somos was doing for the election, he signed up. “I said, ‘Hey, it sounds like I’d be a good fit for me,’ ” he said.

Villanueva studied communications in community college and said what he learned has helped him in Nevada. “Every interaction is different,” he said. “If they’re on the fence, really, it’s because they’re not really educated on, you know, who is actually running or what it is that they’re actually doing for the community. So I kind of try to take some time and at least give them some points or two that might relate to what it is that we talked about that is affecting them.”

At most doors, he hears about prices and the economy. “I would say 90 percent of the people that I talk to, [it’s] health care or, you know, child care, that also affects them. But, yeah, it’s mainly the finances, the way inflation [is hitting them].”

The canvassers talked about the personal struggles they have encountered as they’ve gone from house to house. Lozoya described a woman who aspires to buy a home but is having trouble saving enough money because her rent keeps increasing. “She’s like, ‘How can I afford something when my wages are the same and my rent keeps going up?” Lozoya said. “And I was like, I know how you feel. Same thing happened to me.”

For Roldan, it was a man who spoke to her in quiet tones because he did not want a neighbor to hear. He told her he was being evicted and had no home to go to. She has come to see her own circumstances differently. She once thought of herself as poor, but no more. “I have knocked doors where I see little kids,” she said. “I cannot tell you exactly, but I know that is poverty.”

Villanueva mentioned an elderly woman with a son who has Down syndrome and who worried about what might happen to him if something happened to her, whether the health-care system would be able to provide for him. “They just want things to get better,” Villanueva said.

Door to door, one vote at a time

Back on the streets, Roldan and Lozoya go door-to-door again. This time, the hour is later, the heat less oppressive. But the work is no less difficult. At a few houses, they are greeted warmly; at others, hesitantly. At one house, a father is sleeping; at the next, a husband who is the voter on their rolls is asleep. At the next, a sign says, “This house protected by the good Lord and a gun.”

At the 10th house of the afternoon, a young man with a red beard and wearing a Batman T-shirt and his mother-in-law greet them warmly. He says he doesn’t have cable TV and has “turned down the politics,” but they both say they are “blue” voters and cheerfully pose for the Culinary Workers photographer who is trailing along.

Later along their route, Roldan and Lozoya engage one man in a spirited conversation in Spanish. He favors rent stability but doesn’t want to hear about politics or candidates. Later, there is more positive reinforcement when a man tells them, “I’m a Democrat,” and pointing to the literature they hand him, he adds, “These are Democrats. I’m voting for them.” A few doors later comes a different response. “We’re not really engaged,” a man says. “Thank you very much.”

Culinary Workers Union Local 226 members Elsa Roldan and Alma Lozoya go door-to-door in a Las Vegas neighborhood.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan