Ospreys Had Safety Issues Long before They were Grounded. A Look at the Aircraft’s History

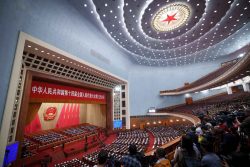

In this image provided by the U.S. Navy, Aviation Boatswain’s Mate 2nd Class Nicholas Hawkins, signals an MV-22 Osprey to land on the flight deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln in the Arabian Sea on May 17, 2019.

10:56 JST, December 8, 2023

WASHINGTON (AP) — When the U.S. military took the extraordinary step of grounding its entire fleet of V-22 Ospreys this week, it wasn’t reacting just to the recent deadly crash of the aircraft off the coast of Japan. The aircraft has had a long list of problems in its short history.

The Osprey takes off and lands like a helicopter but can tilt its propellers horizontally to fly like an airplane. That unique and complex design has allowed the Osprey to speed troops to the battlefield. The U.S. Marine Corps, which operates the vast majority of the Ospreys in service, calls it a “game-changing assault support platform.”

But on Wednesday, the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps grounded all Ospreys after a preliminary investigation of last week’s crash indicated that a materiel failure — that something went wrong with the aircraft — and not a mistake by the crew led to the deaths.

And it’s not the first time. There have been persistent questions about a mechanical problem with the clutch that has troubled the program for more than a decade. There also have been questions as to whether all parts of the Osprey have been manufactured according to safety specifications and, as those parts age, whether they remain strong enough to withstand the significant forces created by the Osprey’s unique structure and dynamics of tiltrotor flight.

The government of Japan, which is the only international partner flying the Osprey, had already grounded its aircraft after the Nov. 29 crash, which killed all eight Air Force Special Operations Command service members on board.

“It’s good they grounded the fleet,” said Rex Rivolo, a retired Air Force pilot who analyzed the Osprey for the Pentagon’s test and evaluation office from 1992 to 2007 as an analyst at the Institute for Defense Analyses, and who previously warned military officials that the aircraft wasn’t safe. “At this point, they had no choice.”

The Osprey has become a workhorse for the Marine Corps and Air Force Special Operations Command and was in the process of being adopted by the Navy to replace its C-2 Greyhound propeller planes, which transport personnel on and off at-sea aircraft carriers.

Marine Corps Ospreys also have been used to transport White House staff, press and security personnel accompanying the president. White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said they also are subject to the standdown.

While the Ospreys are grounded, Air Force Special Operations Command said it will work to mitigate the impact to operations, training and readiness. The command will continue to fly other aircraft and Osprey crews will continue to train on simulators, spokeswoman Lt. Col. Becky Heyse said.

It was not immediately clear how the other services will adapt their missions.

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE CLUTCH

The first Ospreys only became operational in 2007 after decades of testing. But more than 50 troops have died either flight testing the Osprey or conducting training flights over the program’s lifespan, including 20 deaths in four crashes over the past 20 months.

In July, the Marine Corps for the first time blamed one of the fatal Osprey crashes on a fleet-wide problem that has been known for years but for which there’s still not a good fix. It’s known as hard clutch engagement, or HCE.

The Osprey’s two engines are linked by an interconnected drive shaft that runs inside the length of the wings. On each tip, by the engines, a component called a sprag clutch transfers torque, or power, from one proprotor to the other to make sure both rotors are spinning at the same speed. That keeps the Osprey’s flight in balance. If one of the two engines fails, the sprag clutch is also a safety feature: It will transfer power from the working side to the failing engine’s side to keep both rotors going.

But sprag clutches have also become a worrying element. As the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps began looking at HCE events following incidents in 2022, they determined that the clutches may be wearing out faster than anticipated.

Since 2010, Osprey clutches have slipped at least 15 times. As the system re-engages, hard clutch engagement occurs. In just fractions of a second, an HCE event creates a power spike that surges power to the other engine, which can throw the Osprey into an uncontrolled roll or slide. A power spike can also destroy a sprag clutch, essentially severing the interconnected drive shaft. That could result in the complete loss of aircraft control with little or no time for the pilots to react and save their Osprey or crew, Rivolo said.

In the 2022 crash of a Marine Corps MV-22 in California that killed five Marines, hard clutch engagement created an “unrecoverable, catastrophic mechanical failure,” the investigation found. The fire was so intense it destroyed the Osprey’s flight data recorder — another issue the Marines have pushed to fix, by requiring new flight data recorders to be better able to survive a crash.

OSPREYS HAVE BEEN GROUNDED BEFORE

After Air Force Special Operations Command experienced two hard clutch engagement incidents within six weeks in 2022, the commander, Lt. Gen. James Slife, grounded all of its Ospreys for two weeks. An undisclosed number of Ospreys across the military were grounded again in February 2023 as work began on clutch replacements.

But getting replacements to all the aircraft at the time depended on their availability, Slife said in 2022.

And even that replacement may not be the fix. Neither the services nor defense contractors Bell Textron or Boeing, which jointly produce the Osprey, have found a root cause. The clutch “may be the manifestation of the problem,” but not the root cause, Slife said.

In last week’s crash, Japanese media outlet NHK reported that an eyewitness saw the Osprey inverted with an engine on fire before it went down in the sea. If eyewitness accounts are correct, Rivolo said, clutch failure and a catastrophic failure of the interconnected drive shaft should be investigated as a potential cause.

After its investigation of the 2022 crash, the Marine Corps made several recommendations, including designing a new quill assembly, which is a component that mitigates clutch slippage and hard clutch engagement, and requiring that all drivetrain component materiel be strengthened.

That work is ongoing, according to the V-22 Joint Program Office, which is responsible for the development and production of the aircraft. A new quill assembly design is being finalized and testing of a prototype should begin early next year, it said.

WHISTLEBLOWER QUESTIONS

Materiel strength was the subject of a whistleblower lawsuit that Boeing settled with the Justice Department in September for $8.1 million. Two former Boeing V-22 composites fabricators had come forward with allegations that Boeing was falsifying records certifying that it had performed the testing necessary to ensure it maintained uniform temperatures required to ensure the Osprey’s composite parts were strengthened according to DOD specifications.

A certain temperature was needed for uniform molecular bonding of the composite surface. Without that bond, “the components will contain resin voids, linear porosity, and other defects that are not visible to the eye; which compromise the strength and other characteristics of the material, and which can cause catastrophic structural failures,” the lawsuit alleged.

In its settlement, the Justice Department contended Boeing did not meet the Pentagon’s manufacturing standards from 2007 to 2018; the whistleblowers contended in their lawsuit that this affected more than 80 Ospreys that were delivered in that time frame.

In a statement to The Associated Press, Boeing said it entered into the settlement agreement with the Justice Department and Navy “to resolve certain False Claims Act allegations, without admission of liability.”

Boeing said while composites are used throughout the V-22, the parts that were questioned in the lawsuit were “all non-critical parts that do not implicate flight safety.”

“Boeing is in compliance with its curing processes for composite parts,” the company said. “Additionally, we would stress that the cause of the accident in Japan is currently unknown. We are standing by to provide any requested support.”

ONGOING FIXES

The V-22 Joint Program Office said that since the 2022 incidents, significant progress has been made toward identifying the cause of the hard clutch engagement.

“While the definitive root cause has not yet been determined, the joint government and industry team has narrowed down the scope of the investigation to a leading theory,” it said in a statement to the AP. “The leading theory involves a partial engagement of some clutches which have been installed for a lengthy period of time. This has not yet been definitively proven, but the data acquired thus far support this theory.”

Bell assembles the Osprey in a partnership with Boeing in its facilities in Amarillo, Texas. Bell would not comment on last week’s crash, but said it works with the services when an accident occurs. “The level of support is determined by the service branch safety center in charge of the investigation,” Bell spokesman Jay Hernandez said.

In its report on the fatal 2022 crash, the Marine Corps forewarned that more accidents were possible because neither the military nor manufacturers have been able to isolate a root cause. It said future incidents were “impossible to prevent without improvements to flight control system software, drivetrain component material strength, and robust inspection requirements.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Rises on Tech Rally and Takaichi’s Spending Hopes (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan