11:05 JST, September 13, 2025

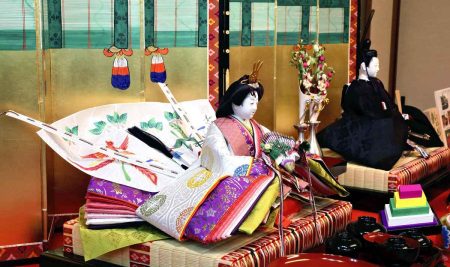

KYOTO — Master doll-maker Yoshiyuki Ohashi folded the arms of a doll forward from its shoulders at his workshop in Kyoto’s Kamigyo Ward. He then pressed a metal spatula against the arms to bend them further inward at the elbows. With each step, the doll, dressed in a dazzling costume, looked as if it were coming to life.

Yoshiyuki Ohashi carefully examines a doll at his workshop in Kamigyo Ward, Kyoto.

The arm-folding process, which involves folding a wire frame that runs through the doll’s arms and torso, determines the overall shape of the doll. With no room for error in this one-shot process, Ohashi, 53, looked very serious.

As he attached the head to the body to complete the process, an elegant Japanese hina doll emerged.

Ohashi is the third-generation head of Ohashi-Ippou, a traditional Japanese doll-making workshop. His grandfather, the workshop’s founder, apprenticed under Nakamura Tahee, the ninth-generation head of Kyoto Urokogataya, a workshop with a more than 300-year history of making dolls. His grandfather subsequently became independent and established his own workshop around 1930.

Ohashi folds the arms of a doll, which he says is the most tense moment.

The workshop of Ohashi-Ippou, which doubles as a store, has been located in the ward’s Senbon Demizu district for half a century. The area is close to Senbon-dori avenue, which was once the Suzaku-oji main street of Heiankyo — the ancient capital of Japan — as well as the site of the Heiankyo palace.

The store is filled with dolls in costumes, faithful reproductions of those once worn by courtiers. The historical recreations are reminiscent of the elegant world depicted in emaki scrolls created about a thousand years ago.

Since hina dolls appear in stores around October ahead of the Hina Matsuri Doll Festival on March 3 the following year, production at Ohashi-Ippou starts in July. By scorching-hot August, eight craftspeople are hard at work.

3,000 steps

Ohashi always loved crafts, and the workshop has been his playground since he was very young. For homework in elementary school, he made a hoko float for the Gion Festival using leftover fabric from doll clothes, attracting attention from his classmates. It was natural for Ohashi, who grew up watching artisans at work, to take the reins of the family business.

After studying Buddhism in college, he worked at a kimono wholesaler for about three years. At 25, he apprenticed under his father Yoshio, now 84, who was head of Ohashi-Ippou at the time. Ohashi pushed himself to master doll-making techniques in five years, although it is said to usually take 10 years.

A bundle of igusa rush grass, which will form the torso of a doll, is shaped with a knife.

Ohashi used to go to the workshop even on weekends to compare his work with his father’s, studying the positions and angles of the arms of his father’s dolls. If a doll’s arms are positioned too high, it looks awkward, and if its face is tilted upward, it looks expressionless.

“I’ve only recently figured out how to create natural poses and expressions,” he said.

A master doll craftsman begins their work by ordering rolls of fabric, which bear tiny patterns befitting the small dolls. About 130 pieces of fabric are necessary to make costumes for a pair of hina dolls — the obina (male) and mebina (female) — and an equal number of washi Japanese paper sheets are needed for the lining.

Fabric is cut based on a pattern.

The fabric is cut and sewn by hand to make the clothing, which is then fitted to the torsos of the dolls. The torsos are made by wrapping washi paper around a bundle of igusa — rush grass usually used to make tatami mats. There are as many as 3,000 steps in the doll-making process. The head, limbs and accessories are made by dividing tasks between specialized artisans.

“Each part is made using traditional craftwork refined over many years in Kyoto,” Ohashi said. “My role is to bring together the techniques of other artisans.”

With passion

Hina dolls have a history dating back about 1,000 years. It was a time when medical care was underdeveloped, and people would transfer their fears of sickness and disaster into human-shaped dolls and release them into the sea or a river as a ritual for children’s safety.

The tradition is said to have been combined with the act of playing with dolls, done by children from upper-class families, and taken on the current form of the Hina Matsuri festival about 400 years ago.

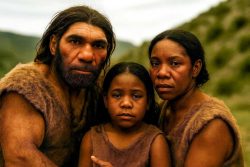

A mebina female doll and obina male doll made by Ohashi

However, the environment surrounding hina dolls has been changing in recent years. With a shift toward nuclear families and a declining birthrate, it has become popular to place only obina and mebina dolls rather than setting up a tiered display with other dolls representing their attendants. Smaller-sized dolls that can be displayed in apartments are also enjoying popularity.

Nevertheless, Ohashi’s devotion to dolls remains unchanged.

“I want to respect the feelings of families who wish for their children’s healthy growth,” he said. “I will continue to make dolls with the same passion as a parent who loves their child.”

His dolls, which showcase exquisite artisanship and have a 1,000-year history, will likely continue to watch over children with their gentle smiles.

***

If you are interested in the original Japanese version of this story, click here.

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Maki-e Artisan Uses Brilliant Skill to Preserve Traditional Lacquerware Craft

Related Tags

Top Articles in Features

-

Tokyo’s New Record-Breaking Fountain Named ‘Tokyo Aqua Symphony’

-

High-Hydration Bread on the Rise, Seeing Increase in Specialty Shops, Recipe Searches

-

Japanese Students Use Traditional Pickle to Create Novel Wagashi Confectionery

-

My Spendthrift Mother Constantly Asks Me for Money

-

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Craftsman Works to Keep Tradition of ‘Kinran’ Brocade Alive Through Initiatives, New Creations

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts