Artist Gyoji Nomiyama speaks in an interview at his studio in Itoshima, Fukuoka Prefecture, on Dec. 14.

11:30 JST, February 9, 2023

FUKUOKA — Artist Gyoji Nomiyama celebrated his 102nd birthday in December. The recipient of the Order of Culture still paints and even makes appearances at his exhibitions. At his studio in Itoshima, Fukuoka Prefecture, Nomiyama spoke to The Yomiuri Shimbun about his passion for painting and his memories of coal mines, a recurring theme in his work.

“When I was in my 90s, everyone would remind me there were only a few years left until I turned 100. But when I became a centenarian, they started asking me to live forever. I thought it was funny,” Nomiyama said in front of his birthday cake.

Nomiyama, a pioneer of Western-style painting in Japan in the postwar period, found fame for portraits he created during his stay in Paris in the 1950s.

The artist lives in Tokyo but has had a studio in Itoshima for about 50 years.

He wakes up at around 8 a.m., has breakfast and naps until noon. He then paints from noon until midnight, taking naps intermittently throughout the day.

Three oil paintings he was working on were leaning against a wall in his studio. The paintings were covered with strong lines in black, red and brown, but Nomiyama insisted they were not abstract paintings.

“My paintings depict scenery from my imagination,” he said. “It does not mean I paint things that don’t exist. I paint memories of landscapes I’ve seen.”

Nomiyama was born and raised in Iizuka, Fukuoka Prefecture, where his father operated a coal mine. He lived in the city until he entered the Tokyo Fine Arts School, predecessor of the Tokyo University of the Arts.

Black coal fields were a familiar scene for Nomiyama in his youth, and the artist often depicts such landscapes in his paintings.

“The nature inside me is something processed, and the smoke and steam of the coal mine are combined in it so there is nothing graceful or soft in my paintings. The colors are ashen and the ground is hard,” Nomiyama said.

Bold black lines feature in his works, giving the paintings a harsh appearance. Nomiyama remembers seeing trees being cut down when his father was on survey trips in the mountains. “I thought they were doing something cruel. I was 10 years old at the time, and I was cheering for nature, telling it not to lose to humans and to rebel,” he said.

The artist was happy to discover that the view from the Nomiyama Gyoji Gallery, which opened last summer in Iizuka, was now a mountain blanketed in green — a dramatic transformation from the past when the site had been used as a coal mine waste dump.

“‘Nature has won,’ I thought,” he said. “I wondered if I could express in my painting the joy of regeneration from something savage and artificial that destroyed nature. I would like to depict things with a cosmic perspective.”

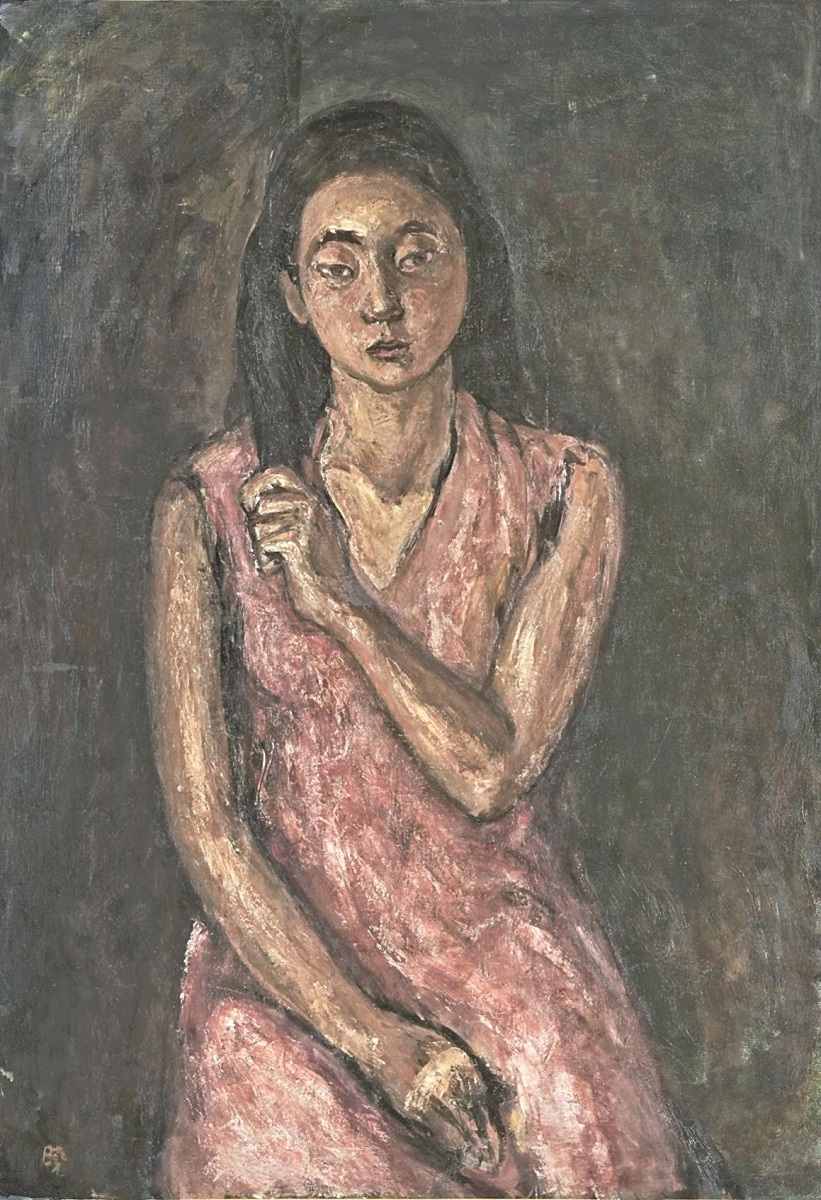

Gyoji Nomiyama’s “Portrait of My Sister,” completed in 1943, from the collection of the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art

An exhibition featuring 60 pieces by Nomiyama is being held at the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art through Sunday.

The oldest piece on display, “Portrait of My Sister,” was a graduation project Nomiyama painted in 1943 at the Tokyo Fine Arts School before joining the war effort.

According to Nomiyama, he had wanted to use a style of painting known as Fauvism, characterized by strong colors and bold brushwork, but he decided to go with a more moderate realism style as knew his mother would be coming to Tokyo to see the exhibition.

“I made a quiet painting that would please my professors so that my mother would not be sad. That’s why I don’t like this painting,” he said.

“This is not simply an example of Nomiyama’s early work,” said Rui Okabe, curator for the Fukuoka Prefectural Museum of Art. “It is a valuable piece that reflects a situation in which an art student who was about to get conscripted painted a person who was important to him.”

Top Articles in Culture

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Chofu, Tokyo; Unique, Surreal Works Draw Steady Crowds

-

Japanese Film, Anymart, Wins Critics’ Award at International Film Festival in Berlin, Director’s Debut Feature Film Shocks Audiences

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan