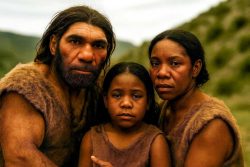

Daut Gashi talks about air pollution caused by coal-powered thermal power plants in Krushevc, Kosovo, on Nov. 7.

November 19, 2021

PRISTINA — Coal-powered electricity generation was an important topic at the recent COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, but heavily coal-reliant Kosovo remained out of the loop.

At the 26th session of the Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which closed Nov. 13, coal was in the spotlight because thermal power plants that burn coal emit large amounts of carbon dioxide.

Kosovo, a small country on the Balkan Peninsula, relies on coal for about 95% of its electric power.

A shift to other energy sources has not progressed in the country because of fiscal hardship, and thus Kosovo has been left behind in the debates about decarbonization.

Air pollution

When I got out of a car near the Obilic coal-powered thermal power plant about 10 kilometers west of Pristina, my nose was hit by a smell like melted vinyl.

From the plant’s chimneys, pale yellow smoke billowed into the upper air, where it visibly lingered.

Kosovo has the world’s fifth-largest known deposit of brown coal, roughly estimated as enough to supply the small country with electric power for more than 1,000 years.

Though electricity bills in Kosovo are said to be the lowest in Europe, large amounts of soot are discharged from burning brown coal.

According to a World Bank estimate, the effects of air pollution kill about 760 people in Kosovo every year.

Daut Gashi, 77, who has lived in Krushevc Village near the power plant for more than 50 years, was infected with the novel coronavirus in spring this year. An X-ray showed white shadows across his lungs.

People with weakened lungs are presumed to be more vulnerable to the novel coronavirus, but the precise causal link between the power plant and susceptibility to the virus is unknown.

Gashi said, “Most residents in this village were infected.”

Financing cut off

Kosovo has five coal-powered electric power generators that started operating in the 1960s to the 1980s.

Because they are seriously aged, the country signed a construction contract for new power plants with a British electric power company, but the contract was annulled ahead of COP 26.

The World Bank also decided on a policy to discontinue all aid for coal-powered electric power generation, and discontinued such aid to Kosovo in 2018.

The World Bank and others encourage Kosovo to shift to renewable energy sources, but wind power accounts for 1% of the country’s electricity production and solar power accounts for less than 0.1%.

It is estimated that the total investment necessary for renewable energy sources to completely replace coal by 2050 would be €3.7 billion to €4.2 billion (about ¥486 billion to ¥550 billion).

The amount is equivalent to half of Kosovo’s GDP, and thus a heavy burden on the country, which is still working to rebuild from the aftermath of war.

Kosovo’s electric power supply is unstable, and blackouts often occur in provincial areas.

Burim Piraj, 55, who runs a meat-processing business in Dragash in the south of the country, said blackouts sometimes continue all day, meaning that an in-house gasoline-powered generator is essential for him to operate his freezer.

“Wind power and solar power are rather unreliable. Using abundant coal is the only choice,” he said.

Unmeetable deadline

Kosovo is not a member of the United Nations, and it did not send delegates to COP26. There was little coverage of the climate conference in local media.

Enver Hoxhaj, a former foreign minister of Kosovo, posted a message of disappointment on his Facebook page: “No one from Kosovo was at the Glasgow climate summit.”

Kosovo has not yet presented a goal for reducing its greenhouse gas emissions, and its economy ministry has refrained from comment on the COP26 discussions.

Milot Morina, a member of a German environment protection organization, said that as long as Kosovo can use coal at low cost, it will be impossible to abolish coal-powered generation by 2050.

There are small countries, like Kosovo, where many people are unaware that decarbonization is even being discussed, and where there are no reduction goals.

Bringing such countries into the global discussion is a task for the international community.

Kosovo’s land area is about 11,000 square kilometers, which is almost the same as Gifu Prefecture. About 1.8 million people live in the country, and about 90% are of Albanian ethnicity.

After the end of World War II, Kosovo became an autonomous region in Serb Republic of what was then Yugoslavia. In the 1990s, pro-independence residents and Serb security forces went into an escalating armed conflict. Kosovo declared its independence in 2008.

Top Articles in World

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanese National

-

South Korea Tightens Rules on Foreigners Buying Homes in Seoul Metro Area

-

Govt to Utilize ODA for Ensuring Economic Security; Securing Energy, Critical Minerals Sought

-

Ukrainian Ambassador Closely Watching Japan’s Revision of Defense Export Rules, Hopes for Future Arms Support

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts