A photo of Lawrence Riley is displayed inside his family’s home. He died early in 2020 of covid-19.

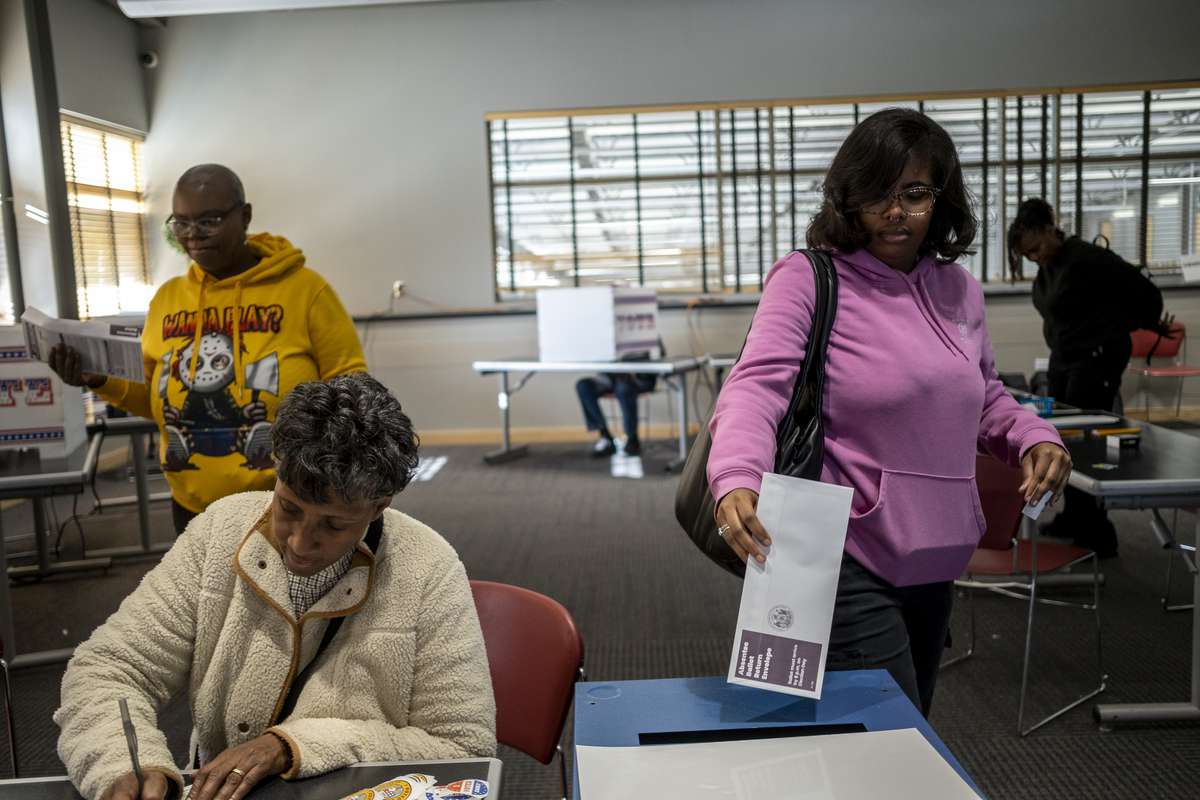

Linda Riley, left, and her daughter Whitley Riley, right, vote on the day they cast their ballots.

15:22 JST, November 4, 2024

MILWAUKEE – On the Saturday morning Whitley Riley woke up to cast her ballot for Vice President Kamala Harris, she noticed a Facebook message from a cousin pleading for a more radical change.

“Everyone should vote for cornel west for president!!” the cousin wrote, because she was fed up with both the Democrat and former president Donald Trump. “Literally anybody else.”

“I am not sure my people are taking this seriously,” Riley, 24, told herself. Had her cousin forgotten what it was like to exist under a Trump presidency? Riley remembered the Charlottesville rally, Trump’s disrespect for civil rights hero John Lewis, the insults to American cities. And then, in March 2020, his administration’s inaction devastated her.

Riley’s father, Lawrence, was the first person in Milwaukee to die of covid-19. As Trump initially downplayed the lethal nature of the virus, covid-19 had invaded Black neighborhoods like her own. Health departments in majority-White areas were more likely to receive resources to set up testing sites, distribute masks and engage in public education campaigns, even as rumors proliferated that Black people were somehow immune.

The result was uneven death. By June 2020, Americans living in counties with above-average Black populations were three times as likely to die of the virus than those living in counties that had above-average White populations. In Milwaukee County, 33 of the first 45 people to die were Black. Many of them lived in Riley’s neighborhood, a middle-class enclave known as Sherman Park, and an impoverished community nearby, Metcalfe Park.

Riley had no choice but to figure out a way to heal in socially distanced solitude. On some nights, when grief overwhelmed her, she slinked into her blue Corolla and drove as far as she could comfortably go. She never made it past about 20 miles, to the village of Germantown.

“It was dark and I would see all of these Trump signs and realized I needed to get out of there,” she recalled. “I blamed the government.”

She could not wait to vote him out of office. Voting became an outlet of expression, tragedy mixed with patriotic responsibility.

Trump had initially dismissed the virus as a flu, sparred with his chief medical adviser and instructed Americans not to let the virus “dominate” them. More than 350,000 people died. His fumbling of the crisis was central to his defeat in 2020, but now Riley observed that stories of how people like her dad lost their lives were but a footnote in the 2024 race.

Pandemics tend to be forgotten – public health experts note that hardly any memorials remember the flu of 1918, which killed 675,000. The pundits Riley saw on television described this current phenomenon as “covid amnesia.” But, in Riley’s community, the issue went far beyond simple forgetting.

They looked back at Trump’s administration as a time when their money went further at the grocery store, and they could manage their rental payments, according to interviews held throughout the community. Even Riley said she thinks that, financially speaking, things were better off four years ago.

Now, stories abounded that Black residents – particularly young people and men – were defecting from the Democratic coalition in small but meaningful numbers. In a tight election, some Democrats fretted that disengaged Black voters could hinder Harris’s groundbreaking campaign.

Riley figured the theory was overstated media-babble. But just last month, she attended a baby shower and saw an 18-year-old Black man wearing a red MAGA hat. She followed him when he stepped outside and asked how he could support a man who wanted to loosen penalties for police misconduct.

“I have my reasons,” he told her.

The conversation “really opened my eyes,” she said. Riley took it upon herself to become an informal emissary to help her community remember the perceived dangers of a Trump presidency.

Her boyfriend, Kenneth Bargy, 26, sometimes wondered if she took it too far. When they started dating two years ago, she told him, “A man who doesn’t vote is a dealbreaker for me.” He said he regularly cast ballots, but she searched for his voting records online to verify his account.

She then began searching the names of friends and family members to check their registration status, so she could figure out whom she needed to hector.

“You don’t have to say anything to them,” Bargy told her recently. “You could just walk away.”

“I can’t just walk away,” she later told her boyfriend. “I have to say something because I’m my father’s child.”

***

Her father called her “Pistol.” Riley is whip-smart and candid; 5-foot-3 with silver framed glasses and a humble smile.

Lawrence Riley, a firefighter and Navy veteran, had impressed upon her when she was growing up that she needed to be an open-minded, informed and ambitious citizen. They would watch cable news together to discuss politics. Mother-daughter dates were trips to the polls, where Riley’s mother, Linda, told her that a vote was a small way to shape a country that never fully respected them.

Now the country was on the cusp of a tight, contentious election, and her state was key to its outcome. The signs were everywhere. Digital billboards loomed over the highways that carve up this segregated city. At one moment, the name “Trump” glowed, casting fluorescent shadows over factory buildings and single-family homes. At other times, it was Harris’s face – accompanied by a pledge to lower grocery costs.

“I can mess with Kamala,” Riley liked to say. She agreed with most of her friends who were upset that Harris wasn’t doing more to prevent the deaths of Palestinians. But she appreciated that Harris was a strong debater, a powerful advocate for reproductive rights, a sorority sister and not an octogenarian.

“When her campaign started, it was a vibe,” her friend, Imaria Noel, 24, told her one Friday evening as they sat on the couch together. Bargy sat nearby.

All three were concerned about Trump returning to the White House. Riley told Noel that she had experienced the cruelty he fomented firsthand.

“We were in the news a lot when my daddy died,” she said. When she’d look through the comments on news articles, she said, many online did not offer condolences or question the country’s pandemic preparation. Instead, they looked at her father’s pudgy belly, and blamed him for having diabetes and other preexisting conditions.

“They didn’t even consider why he might have had diabetes,” Riley said. “Look at what [food] is being offered in our community.”

“Let’s just be all the way honest,” Noel said. “If a White person had been the first person to die with covid, we would see this long processional and all this extra stuff. But, like, when it’s somebody Black, they try to skim it down to make something so small.”

“I’m scared that the underground racists are going to come up and they’re going to feel empowered like they did last time when he won,” Riley said. “That’s why I’m voting against him.”

That’s when Noel disclosed something that made Riley uneasy.

“I’m not voting, because I don’t think it matters,” Noel said. “I don’t mess with Kamala like that.”

Yes, the excitement about a female president was “cute,” but Noel said she had grown tired of campaigns run on vibes. Barack Obama was a vibe – she was 8 when the first Black president was elected, in part because their city had some of the highest Black participation rates in history.

The adults in her life were so joyous back then. But her neighborhood never got much cleaner, nor did she think her schools got better.

In 2016, at 16, she encouraged all her disengaged family members to return to the polls because of a different kind of vibe – she was scared that Trump would take away their civil rights. That did not happen either. Little had changed in her life with the candidate of hope, little changed with the candidate of fear, so why bother getting herself worked up?

She was 20 in 2020, and she regretted being so hard on her family about not voting. The pandemic that compelled Riley to immerse herself in politics repelled Noel. She had been working as an aide in a local nursing home, regularly caring for patients who were succumbing to the virus. The days were long, tragic, lonely and dangerous. And she wondered how politicians supposedly elected to protect people messed up so greatly.

“I feel treated like I’m – ”

She paused to find the right phrase.

“Just a piece in their game,” Noel said. “They’re doing what they want to do when they want to do it, and I’m just having to deal with it every day, regardless of who wins.”

Harris’s speeches felt like more of the same. “It feels like she is going to say whatever she’s going to say to win,” Noel told her. “I would just prefer if she got up there and said, ‘I ain’t gonna lie. I can do some things and I can’t do some things.’”

“We get the TV them,” Bargy interrupted. “We don’t get the real-version person. That’s why it be hard to vote.”

Riley shot him a look.

“I’m voting, baby,” he assured her.

“When you Black,” Noel said, “you’re supposed to use your voice to vote, because Black people went through a lot of stuff to be able to vote. I feel I’m very grateful for them, all the hard work they did, and I really, really appreciate it.”

But she felt the next step in her people’s actualization as full Americans was to reject casting ballots out of fear, obligation or cynicism. She wanted to lend her support to a vision of the country that excited her.

Riley tried to gather her thoughts. She suggested that Noel think beyond the presidency and consider local leaders and referendums, some of which would make it harder for Black people in Wisconsin to exercise their right to vote.

Riley tried to personalize her feelings to send a message. She talked about how terrible she’d feel if she didn’t vote. “If Trump wins, I’m going to be like, ‘Damn, what if my one vote could’ve did something?’” she said.

They went back and forth for about an hour. But Riley’s reasoning was working. Noel told Riley that, honestly, she was no longer 100 percent sure she could sit out the election.

“My girlfriend’s been on me, too,” Noel said “I guess right now I’m 75-25. In my brain, this is the most I’ve teeter-totted about it.”

***

McCurtis, right, prepares canvassers on their door-knocking mission in Milwaukee, in late October.

Many in Sherman Park and Metcalfe Park shared Noel’s sentiment, according to a Washington Post analysis. Nearly half of eligible voters in those areas cast ballots in 2020, far below the national average of 66 percent.

In the first days of early voting, Democratic observers were concerned that the share of early votes from Milwaukee was lagging. Obama was dispatched to draw out voters on Harris’s behalf on Sunday.

Danell Cross, who runs the nonprofit Metcalfe Park Community Bridges with her daughter Melody McCurtis, felt neither candidate has connected their policies with the community’s needs: canceling student debt, raising minimum wage, police reform, expanding job training opportunities.

Harris, Cross said, will say “we’ll give you money to start your own business, but how is that supposed to help people who are low-income and no-income? How do you get from a minimum wage job to owning your own business?”

Meanwhile, no part of their community would make a highlight reel of President Joe Biden’s accomplishments.

There are no plants here that make computer chips. Biden’s lead pipe replacement program has yet to replace a single pipe in the neighborhood. And the antipoverty agency that was supposed to distribute funds from the stimulus package closed down in April, mired in scandal.

By the end of October, “We Won’t Go Back” signs were wrapped around electric poles along North Avenue. But the street was still peppered with abandoned carpet shops and bars and day cares and churches and beauty supply stores – all boarded up, sitting next to rocky, vacant lots.

The women at Community Bridges were organizing election-week barbecues and paid young organizers to knock on doors. Many of the organizers – Black people under 35 – did not plan to vote themselves, but relished taking a job at $17.50 an hour.

After a surge in private donations to Black-led organizations in 2020, McCurtis and Cross had enough to purchase vacant lots to rebuild their community. They placed a large shed on one of them and painted the words, “Love, Feed and Teach the People,” on it. Inside, they stored diapers, coats and shoes. Once a week, they opened the shed so residents could sift through it and take the wares.

Those weekly sessions also gave them a continued opportunity to entice residents to vote. Each visitor got pamphlets about the candidates and a quiz from McCurtis – if they voted, when they planned on doing so, if they needed a ride to a polling site or a phone call to remind them go.

“I prefer to vote on the actual day,” of the election, a man dressed all in denim, sporting a thick white mustache, told her.

“We’re just worried about dangers that might happen on Election Day,” said McCurtis, alluding to potential meddling.

“I already live in the most dangerous neighborhood in Milwaukee!” he said.

Despite the troubles afflicting their neighborhoods, Cross said she thought political observers did not truly understand the rationale of Black voters.

“Black people have always known the risk of losing democracy and we as Black women have had the burden of trying to save it,” Cross said. “What’s exciting now is that it seems like more people, White people, are recognizing that risk.”

***

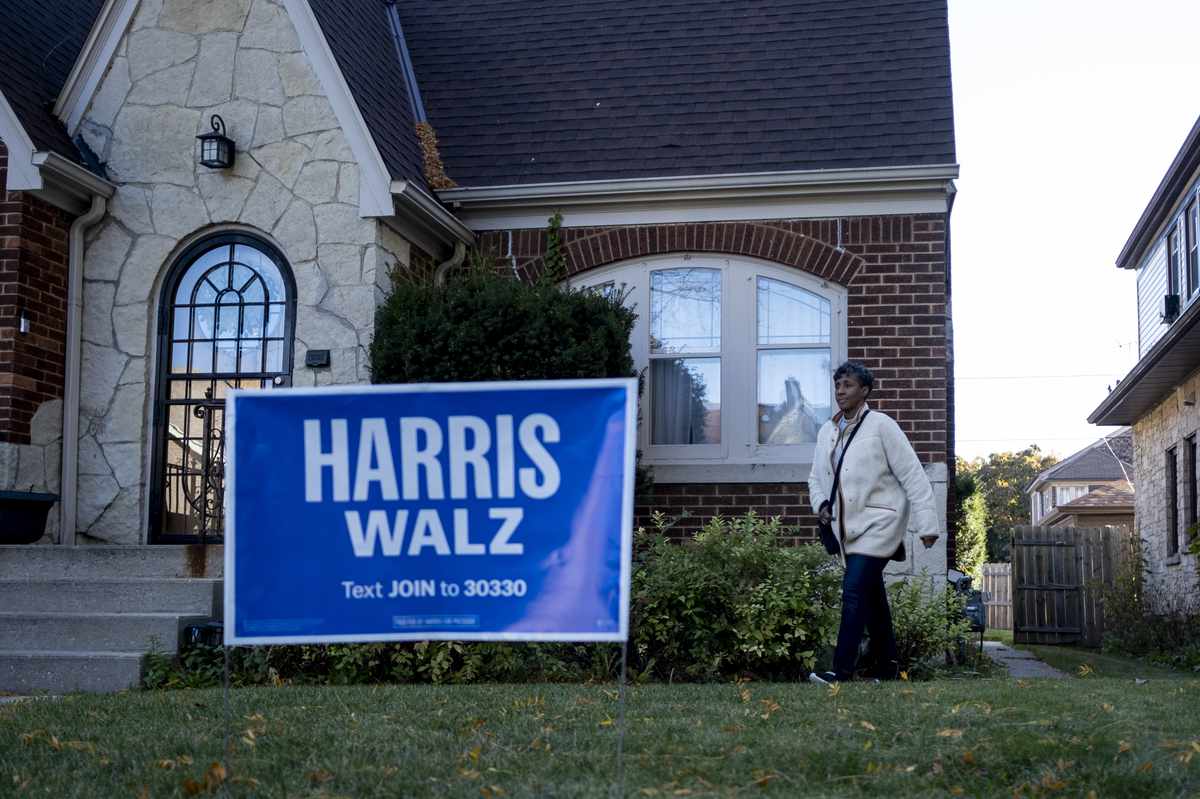

Linda Riley walks past her home in Milwaukee.

In the dining room of Whitley Riley’s childhood home hangs a framed photo of her father, decked in a fedora and stroking his chin, clouds in the background.

After he died, Riley began to think about her nickname, Pistol. She actually had no idea how she got it.

Her mother, Linda, told her it did not have to do with her fiery personality. He was comparing her with how he thought about his firearm.

“He said you would always be with him,” she said.

On the morning that the two were set to cast their vote in late October Linda couldn’t find Pistol. Polls opened at 9 a.m., and she was nervous that she may have to wait in line.

Riley walked through the house around 9:15 a.m. The morning had already been momentous. She didn’t know if her comments on Facebook were successful in swaying friends away from third-party candidates, but she learned her talk with Noel had changed her mind – kind of.

“I can use my voice for the local elections,” Noel told her, “even if I leave president blank.”

“Progress can be slow,” Riley reflected. “But it’s still progress.”

Now her mother was walking out the door.

“You ready?”

The two drove to the local library, the early voting site for Sherman Park and Metcalfe Park. Usually, it would take a few minutes to vote and leave. But this time, the parking lot was full. The voting line spilled out of the voting booths, down the stairs and into the lobby.

The Rileys took their place in line. As they waited, a man named Jack Dills, Sr., 63, looked at the expanding, diverse swath of voters. He clasped his hands and looked to the heavens.

“We’re voting!” Dills said. “I haven’t seen this kind of line since Obama in 2008!”

There was a young man in his 30s ahead of the Rileys. A precinct worker announced the man was a first-time voter. Those in line applauded.

“Maybe we are taking this election seriously,” Whitley Riley said.

Behind the Rileys were a mother and son, Nicole and Nigel Quezaire.

In an interview after they cast their ballots, Nigel, a 29-year-old transportation worker, said he was not planning to vote until his mother forced him to do so.

“That’s right,” she said.

“I didn’t think I had enough time to do my research, but she kept insisting, ” he said. As he Googled candidates and their platforms, he became terrified about the plans to get rid of federal social programs laid out in Project 2025, a Heritage Foundation blueprint scribed by numerous Trump officials to guide his second term. Trump has claimed that he has nothing to do with the plan, but Nigel did not believe him.

“It seems like it is taking things back to a time in America that we don’t want to go back to,” Nigel said. “But a woman president? It has good and bad parts. I mean, women, they are more emotional.”

His mother, Nicole, 49, stared at him.

“I voted for Harris!” he said. “I said it has good parts, too.”

By the time Linda and Whitley Riley walked out of their voting booths, the line for voters was stretching out the door, pushing into the street. An unprecedented enthusiasm was seen across the state; more than 1 million voters, a third of those eligible, had cast ballots in the first week.

“This is exactly what we want to see,” Linda said. Democratic leaders in the state would continue to worry about voter turnout in Milwaukee, but, at this moment, Whitley Riley felt less tense than she had since she saw the MAGA hat at a baby shower.

“Your father would be astonished,” Linda said. “He would vote for a woman. He was raised by a strong woman. He wanted you to be a strong woman. Remember what he used to tell you? That you could be the president?”

Whitley Riley nodded.

“Yes,” she said. “I remember.”

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

American Playwright Jeremy O. Harris Arrested in Japan on Alleged Drug Smuggling

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average as JGB Yields, Yen Rise on Rate-Hike Bets

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Licks Wounds after Selloff Sparked by BOJ Hike Bets (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Buoyed by Stable Yen; SoftBank’s Slide Caps Gains (UPDATE 1)

-

Japanese Bond Yields Zoom, Stocks Slide as Rate Hike Looms

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant; Inspects New Emergency Safety System

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by Deterioration of Japan-China Relations

-

Tokyo Economic Security Forum to Hold Inaugural Meeting Amid Tense Global Environment

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Security in Interview Ahead of Forum

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi’s Power Plans