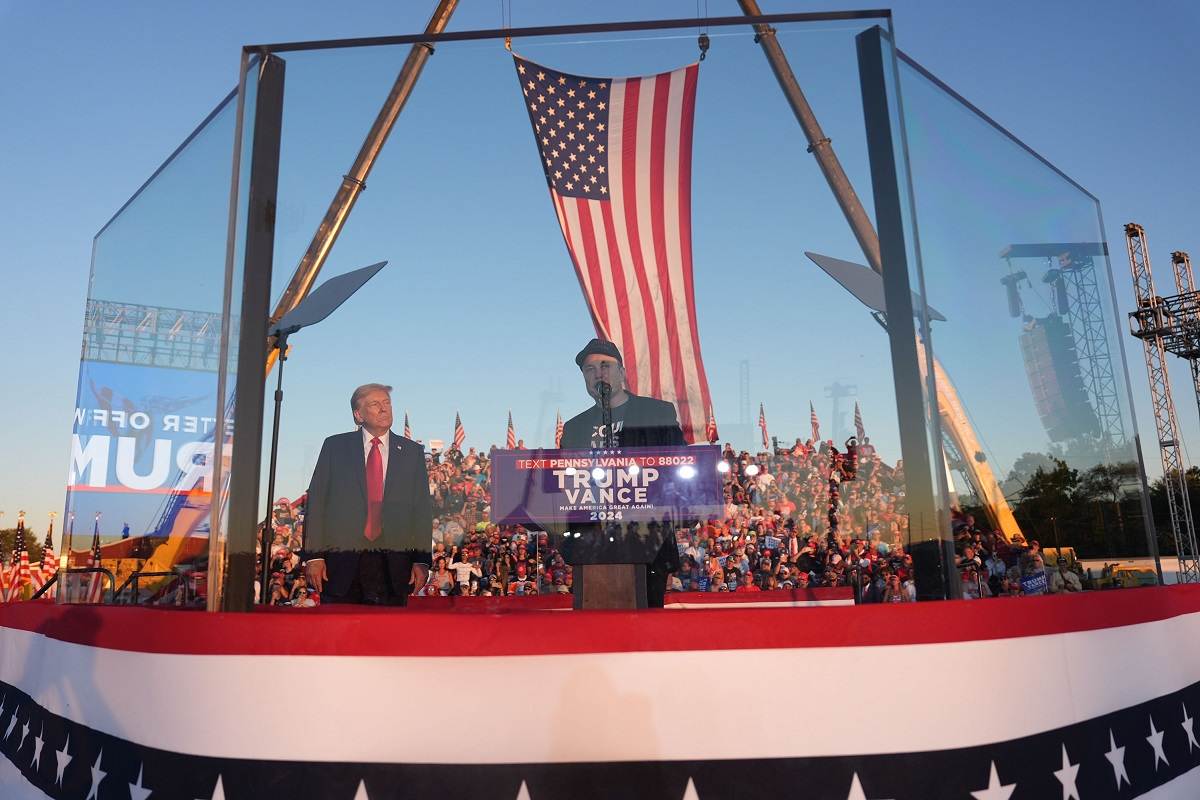

Tesla and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk speaks at a campaign event with former president Donald Trump on Oct. 5 in Butler, Pennsylvania.

12:27 JST, October 28, 2024

NASA has long declared that it intends to send astronauts to Mars, but not right away. First comes landing on the moon, again. Mars remains on the back burner.

That’s not daring enough for Elon Musk, or for his thousands of SpaceX employees who wear “Occupy Mars” T-shirts while cheering the company’s rocket launches. Musk has said on his social media site, X, that it is possible SpaceX will send people to Mars in just four years – and he’s getting a thumbs up from Donald Trump.

“We will land an American astronaut on Mars,” Trump vowed at a rally Oct. 19 in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. “Get ready, Elon, get ready. We gotta land it, we gotta do it quickly.”

At an earlier campaign appearance in Pennsylvania with Musk at his side, Trump said: “We will lead the world in space exploration. … Now, he told me that we’re going to win, and he’s going to reach Mars by the end of our term, which is a big thing. Before China, before anybody, right? And I – my money’s on that guy right there.”

The tightening relationship between Trump and Musk is an unexpected autumnal twist in this election, and it has caught the attention of space policy analysts. No one is quite sure what a Trump-Musk partnership would mean for NASA and for human spaceflight generally if Trump returns to the White House. But Mars is now part of the discussion in a way it wasn’t just a few months ago. And although Musk is already an integral part of NASA’s human spaceflight program, any NASA strategic pivot that speeds up efforts to send humans to Mars could potentially funnel more contracts to SpaceX.

Trump’s campaign did not address specific questions about Musk, Mars and NASA, but senior adviser Brian Hughes touted the creation of the U.S. Space Force as one of Trump’s “greatest accomplishments” and said Trump in a second term would aim to achieve “American superiority in space.”

The Harris campaign and Space X did not immediately respond to requests for comment for this article.

Musk and his SpaceX team have been focused on Mars since the company was founded as a start-up in 2002. Trump was also Mars-centric in comments during his presidency.

In a 2017 conversation with astronaut Peggy Whitson, who was on board the International Space Station as its commander, Trump asked about a Mars mission timeline. Whitson said it would not be until the 2030s and would take international cooperation because of its expense. Trump said, “Well, we want to try and do it during my first term or, at worst, during my second term, so we’ll have to speed that up a little bit, okay?”

In June 2019, Trump went on the social media platform then called Twitter to express impatience with the Artemis mission that his own administration initiated: “For all of the money we are spending, NASA should NOT be talking about going to the Moon – We did that 50 years ago,” he wrote. “They should be focused on the much bigger things we are doing, including Mars (of which the Moon is a part), Defense and Science!”

Weeks later, in an Oval Office meeting to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first lunar landing, Trump pressed NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine on why the agency couldn’t go straight to Mars.

“To get to Mars, you have to land on the moon, they say. Any way of going directly without landing on the moon? Is that a possibility?” Trump asked.

“Well, we need to use the moon as a proving ground, because when we go to Mars, we’re going to have to be there for a long period of time, so we need to learn how to live and work on another world,” Bridenstine answered.

Musk endorsed Trump in July, donated at least $75 million to a PAC supporting the former president and has been holding rallies in Pennsylvania. Trump has promised to appoint Musk as the head of a government efficiency commission. Musk has criticized the pace of regulatory oversight in government agencies, complaining that he can build rockets faster than regulators can approve launches.

Musk has warned that the ability to go to Mars, and even the survival of humanity, depends on a Trump victory.

“While I have many concerns about a potential Kamala regime, my absolute showstopper is that the bureaucracy currently choking America to death is guaranteed to grow under a Democratic Party administration,” Musk wrote on X, the social media company he bought two years ago. “This would destroy the Mars program and doom humanity.”

Moon vs. Mars

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket carrying the company’s Dragon spacecraft is launched on NASA’s May 2020 mission to the International Space Station.

Missions to Mars have to be timed to take advantage of the relative positions of Earth and Mars as they circle the sun, and launch windows open up roughly every two years. There are two launch windows coming up this decade, starting in 2026 and 2028.

SpaceX is developing and testing a new spacecraft, Starship, that the company says could carry a crew to Mars. Musk has said he plans to send about five uncrewed Starships to Mars in 2026 and, if everything goes smoothly, a crewed mission in 2028 – which would be late in the next administration’s term.

It is unclear how NASA might fit into such a mission. NASA already has an ambitious and technically challenging human spaceflight plan with Artemis. The program began when Trump was in office and survived the change in administrations. It enjoys solid bipartisan congressional support despite delays, cost overruns and withering reports from NASA’s Office of Inspector General, which has estimated that Artemis will have cost $93 billion through 2025.

Hovering over America’s lunar aspirations are fears that China could put boots on the ground there first (albeit more than half a century after 12 Apollo astronauts did it wearing American flags on their moon suits). This is not merely about bragging rights. The moon has precious resources, including rare elements that are essential to the manufacturing of modern technologies, said Zaheer Ali, a physicist and space policy expert at Arizona State University.

“Economic development-wise, the moon is the game,” Ali said.

The Trump-Musk partnership comes in an era when human spaceflight has rapidly evolved into a far more commercial industry, with NASA as a paying customer rather than the manager of some missions. But Artemis adheres to the more traditional model, being fully managed by NASA.

The agency has taken pains to spread contracting dollars around and form partnerships with other countries. The mission architecture uses a NASA-owned rocket called the Space Launch System, and a NASA-owned capsule called Orion.

The rocket and capsule projects have been long delayed and over budget, and can’t by themselves put astronauts on the moon. As a result, NASA has contracted with SpaceX to use its Starship spacecraft to ferry astronauts from lunar orbit (where they will have arrived via Orion and the Space Launch System rocket) to the moon’s surface and back. Jeff Bezos’s space company, Blue Origin, also has a contract for a lunar lander in a future Artemis mission. (Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

SpaceX has been on a roll, raking in billions of dollars in government contracts to launch NASA astronauts to the space station and satellites for military and national security agencies. It is now the dominant force in the launch industry. SpaceX’s interplanetary ambitions led to the development of Starship. Earlier this month, the company performed a dazzling display of engineering wizardry, landing a rocket booster into the waiting mechanical arms of the rocket’s launch tower.

But Mars is a hard destination for human beings, regardless of the technological prowess of aerospace engineers. The planet has hardly any air. It shows no sign of life. It lacks a magnetic field, and the surface is bombarded with radiation.

Whereas the moon is never more than three days of spaceflight away – the Apollo 11 astronauts blasted off on a Wednesday and were back home the next week on Thursday – a round-trip mission to Mars would likely take two to three years, said Nujoud Merancy, the lead for strategy and architecture with NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate.

Before NASA attempts such a journey with a crew, there are numerous space systems that need to be developed and tested to ensure a safe and successful mission, she said. NASA currently has no specific target date for any Mars mission, she said.

“One of the biggest challenges is the human system, keeping crew healthy and alive and capable of even exploring Mars once they get there,” Merancy said, adding that there would be physical challenges for astronauts after being weightless during the long voyage.

“Spaceflight and safety is all a matter of risk tolerance and risk acceptance,” she said. “NASA as a government agency, we certainly strive to make sure we understand all the risks associated with the missions and the risks we’re asking our crew members to take.”

Public vs. private

Space policy experts have generally viewed NASA as relatively immune from any dramatic pivots after the election, compared with some government agencies in the executive branch. But the injection of Musk into Trump’s campaign, and the recent comments by Trump about Mars, are impossible to ignore.

A Trump victory in the election could conceivably lead to “a radical refocus on humans to Mars,” said Casey Dreier, head of space policy for the Planetary Society, a nonprofit space science and exploration advocacy organization. Dreier does not think such a pivot is the most likely scenario for the space agency. Still, he notes, “Every time Trump himself has spoken extemporaneously about NASA, it’s about sending people to Mars.”

One possibility is that NASA – which has a current annual budget of about $25 billion – would become “a customer of a SpaceX mission to Mars,” said Greg Autry, associate provost for space commercialization and strategy at the University of Central Florida and a Trump transition team leader for space policy after the 2016 election.

“It needs to not be a NASA mission,” Autry said. “NASA’s management processes and culture are too slow for the aggressive four-year schedule Trump is discussing.”

Musk has energized his thousands of employees with a vision of cities on Mars. He contends that it is essential to human survival, because the Earth remains vulnerable to a catastrophe that could wipe out our species.

In his post on X, Musk wrote in September: “We want to enable anyone who wants to be a space traveler to go to Mars! That means you or your family or friends – anyone who dreams of great adventure. Eventually, there will be thousands of Starships going to Mars and it will [be] a glorious sight to see! Can you imagine? Wow.”

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

American Playwright Jeremy O. Harris Arrested in Japan on Alleged Drug Smuggling

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average as JGB Yields, Yen Rise on Rate-Hike Bets

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Licks Wounds after Selloff Sparked by BOJ Hike Bets (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Buoyed by Stable Yen; SoftBank’s Slide Caps Gains (UPDATE 1)

-

Japanese Bond Yields Zoom, Stocks Slide as Rate Hike Looms

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant; Inspects New Emergency Safety System

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by Deterioration of Japan-China Relations

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Security in Interview Ahead of Forum

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi’s Power Plans

-

Govt Aims to Expand NISA Program Lineup, Abolish Age Restriction