Unbalanced Information Diet: Protecting the Facts / Disinformation on Japan’s Noto Quake Spread for Ad Revenue

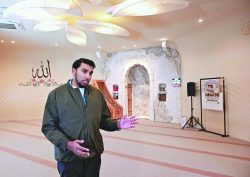

A man looks at his post on X in Lahore, Pakistan, in March. The photo has been partially obscured.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

6:00 JST, April 23, 2024

Since the Noto Peninsula Earthquake on Jan. 1, at least 10 foreign countries have become major sources of false information about the disaster, as social media users there are motivated by the chance to gain impressions and generate revenue. This is the first installment in a series examining various situations in which conventional laws and ethics can no longer be relied on in the digital world, and exploring possible solutions.

***

SARGODHA, Pakistan – A resident of Sargodha, Pakistan, thought something terrible was happening in Japan when he found the words “Japan” and “earthquake” in his native language and video footage of boats and cars being swallowed up by black water and mud when he was browsing X, formerly Twitter, on his smartphone on Jan. 1.

The 39-year-old man was struck with the number of views on posts featuring the video. Some of them had amassed hundreds of thousands of impressions.

Thinking it was a “chance to make money,” he immediately reposted the video on X. He also spread images of collapsed houses and landslides he found on the internet. Whether they were really related to the Noto earthquake or not was not his concern.

Japan ‘2nd largest X market’

The man worked as a civil servant for 18 years after graduating from university. He lives in a brick house with about 10 of his relatives. Although he was financially stable, he needed to earn more for his eldest son, 16, who aspires to become a doctor.

He quit his job in October 2023 to start a new business to make a fortune.

That was around the time he read an article in which Elon Musk, the owner of X Corp., said people now can earn a living on X.

X began distributing ad revenue in summer 2023 to X users whose accounts have at least 500 followers and posts made in the past three months have been viewed more than 5 million times.

The man soon opened an X account and began dedicating six to seven hours a day to posting.

Initially, the number of views on his posts showed little growth. However, when he started making Noto quake-related posts, utilizing machine translation, he soon accumulated 3.6 million views.

More than 40 million people are estimated to use X each day in Japan. “I started making more posts with Japan in mind after learning from a friend that Japan is the world’s second-largest X market,” he said. Eventually, he was eligible to receive revenue from X.

On Feb. 1, one month after the quake, he was paid by X for the first time. Since X’s payment system was not available in Pakistan, he had the money transferred to a bank account in another country.

His first payment was $37. The average annual income in Pakistan is about $1,600. “I thought ‘I want more,’” he said.

Asked whether he was aware that the video of black water and mud he spread was taken during the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, he said, “I don’t know anything about that. I just wanted impressions.”

“I’m sorry for what I did to Japan. But I want to continue posting on X to make money,” he said.

‘Impression farming’

Changes to how X operates have led to an increase in the number of so-called impression farming posts. The for-profit practice disregards the accuracy of information and is behind the large-scale production of false information.

The Yomiuri Shimbun examined 108 of the accounts that had posted false information about the Noto earthquake on X.

Thirteen countries were listed as the residence of holders of 63 of the accounts, and 70% of those posts were from users from just five developing countries, including Pakistan, Nigeria and Bangladesh. Fictitious rescue requests and posts by those impersonating as quake victims were also confirmed.

“For the poor in developing countries, earnings on X can be enough to feed an entire family,” said Yuya Shibuya, an associate professor of social informatics at the University of Tokyo, who investigated disinformation related to the Noto quake. “Since it is easy to start social media accounts, people may have been motivated to earn impressions.”

The earthquake is said to be the first major disaster in Japan where a large amount of false information was spread from abroad. Serious action is needed as the adverse effects of the “attention economy,” where click-through rates are prioritized over the accuracy of information, are accelerating.

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Masako Ikeda, Voice of Maetel in ‘Galaxy Express 999,' Dies at 87

-

Japan Defense Agency to Develop AI Intelligence Analysis System f...

-

Government to Establish ‘Command Center’ for Developing Nuclear P...

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japan’s Momoka Muraoka Takes Silver in...

-

Moai Statue Shows Lasting Bond Between Miyagi Pref. Town, Easter ...

-

Paw Patrol: Larry Marks 15 Years at 10 Downing Street

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japan’s Oguri Wins Para Snowboard Silver at ...

-

CARTOON OF THE DAY (March 13)

Popular articles in the past week

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Surviv...

-

Govt to Utilize ODA for Ensuring Economic Security; Securing Ener...

-

15 Measles Patients Confirmed in Tokyo in Past 6 Days; 1 May Have...

-

Massive Sewer Pipe Found Jutting Out of Highway in Osaka

-

Japan Govt to Tighten Requirements to Receive Permanent Residency...

-

Beckoning Cats Get Makeover to Fit Modern Lifestyles with Sleek D...

-

JR Tokai Breaks Ground on Yamanashi Maglev Station; Will Be Part ...

-

Power Outage Forces About 980 Passengers in Yokohama to Walk to T...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Surviv...

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanes...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

15 Measles Patients Confirmed in Tokyo in Past 6 Days; 1 May Have Come into Contact with Many in Shibuya

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Ibaraki Pref.’s 1st Foreign Bus Driver Hired in Tsukuba

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts