Unbalanced information diet series: Warped lens on the world / Are Social Media Algorithms in Fact Harmless? Studies Fail to Find Polarizing Effect.

Frances Haugen gives a speech at the Cambridge Disinformation Summit at the University of Cambridge on July 28.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

1:00 JST, October 17, 2023

The internet has become a chaotic space, brimming with outrageous, biased and fake information. The so-called attention economy, which generates revenue by getting people to click on or view ads, underpins today’s digital era. This is the fifth and final installment in a series of articles.

***

Algorithms that push posts matching user preferences to social media feeds create “filter bubbles” in which users are surrounded by opinions that are similar to their own, thus widening social divisions — so runs the accepted view. On July 27, four papers were released that may overturn this theory on the digital world.

The papers were partially funded by Facebook-owner Meta Platforms and written by outside researchers.

One paper found that, even when users were shown feeds with no algorithm, this change “did not significantly alter levels of issue polarization, affective polarization, political knowledge, or other key attitudes.”

This study sampled about 40,000 Facebook and Instagram users from September to December 2020, during which time the U.S. presidential election was held. Some users were shown feeds that displayed the most recent posts instead of those chosen by the default algorithm, meaning users did not always see their preferred content.

Showing users the most recent posts substantially decreased the time they spent on the platforms, suggesting that algorithms play a significant role in attracting users and boosting ad revenue.

On the other hand, the paper found that there were no significant changes in the users’ political views. Meta and the paper’s researchers differ on how they interpret this finding.

Nick Clegg, Meta’s president for global affairs and former British deputy prime minister, described the studies as “landmark research papers” on the day they were released.

“The experimental studies add to a growing body of research showing there is little evidence that key features of Meta’s platforms alone cause harmful ‘affective’ polarization,” he said.

However, Joshua Tucker, a professor at New York University and a lead researcher for the project, told The Yomiuri Shimbun: “It does not in any way definitively show that social media and Facebook in particular doesn’t cause political polarization.” He added that had the research been conducted at a different period or in a different country, its findings could have been different.

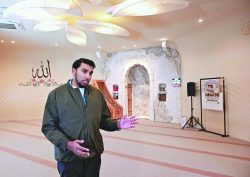

Frances Haugen, a data expert who used to work for Facebook, criticized Meta when she delivered a speech at the University of Cambridge on the day after the papers were released.

“Science, the publisher of the research, said, ‘Hey, if you come out and characterize this research as an exoneration, we will publicly review you,’” she said. “And Facebook did it anyway, because they do what they want to do.”

“To say that that is the experiment that exonerates the algorithms, I think is really, really reductive,” she added.

Haugen speaks in an online interview held at The Yomiuri Shimbun’s building in Tokyo.

‘Conflicts of interest’

Nine years ago, Haugen became unable to walk due to illness. During her rehabilitation, she got support from a friend. But one day she noticed that something about this friend had changed.

He began to share conspiracy theories, claiming that a Jewish investor was funding violent revolutionaries and that the Democratic primary had somehow been stolen. She found it more and more difficult to talk with him.

Haugen believed this change was caused by online posts and algorithms used by social media platforms that suggested misinformation. Losing her close friend became a turning point for Haugen.

Already an expert on algorithms, she grew even more interested in their potential for harm.

“I was hoping that if I could help one person avoid how much it hurt, when I watched [my friend] get radicalized, then it would be worth it,” she recalled. “I didn’t expect to have some, you know, role-changing impact. It was just like, if we can make this problem a little bit less bad. That’s still a worthy cause.”

When she joined Facebook in 2019, she wanted to be on a team that would stop disinformation, conspiracy theories and hate speech.

Once she started working with the team, she realized that harmful content was common. She was shocked to find that exchanges encouraging human trafficking or suicide would be left unchecked on Facebook in non-English-speaking countries.

However, she also felt that Facebook was trying to deal with such problems. The social networking company continued to invest in her team, which by then had about 300 workers.

But immediately after the U.S. presidential election in November 2020, the team was dissolved.

Though the company said it was only integrating the team into a larger department, “that was the moment when I realized that Facebook had kind of lost the will to change,” she said.

Two months later, American democracy was shaken when a crowd of supporters of then U.S. President Donald Trump attacked the U.S. Capitol, in part because of claims spread on Facebook that the election had been rigged.

Supporters of then U.S. President Donald Trump are seen in front of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Haugen blew the whistle on the company, providing some 22,000 pages of confidential documents to a U.S. newspaper. In October 2021, she testified at a U.S. congressional hearing. “The thing I saw on Facebook over and over again was there were conflicts of interest between what was good for the public and what was good for Facebook. And Facebook over and over again chose to optimize for its own interests like making more money,” she said.

Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, refuted the testimony on his Facebook page.

“At the heart of these accusations is this idea that we prioritize profit over safety and well-being. That’s just not true,” he wrote. “For example, one move that has been called into question is when we introduced the Meaningful Social Interactions change to News Feed. This change showed fewer viral videos and more content from friends and family — which we did knowing it would mean people spent less time on Facebook, but that research suggested it was the right thing for people’s well-being. Is that something a company focused on profits over people would do?”

Two years have passed since Haugen’s whistleblowing. How does she view the current online space?

The introduction of the Digital Services Act in the European Union in August, she said, was a step toward improvement. The act requires platform operators, including Meta and X (formerly Twitter), to prevent the spread of disinformation and increase the transparency of their algorithms.

But she said the generative AI systems now gaining popularity lack transparency. Asked about a solution, she suggested social motivation for generative AI companies to invest in safety measures.

That social media platforms also tend to undervalue safety can be seen in the massive layoffs that took place between late last year and this spring at Twitter.

Melissa Ingle, who worked in a Twitter department that handled harmful content, said online space had become filled with hatred as misinformation and hate speech proliferated.

Ingle, 49, was fired from Twitter in November last year, shortly after the company was bought by U.S. entrepreneur Elon Musk. Eighty percent of employees in the department were also dismissed, Ingle said.

Up to this point, harmful content had been monitored by both AI and people, but with the number of monitoring personnel downsized, operations were further automated. Musk defended his company in an online post, saying it was doing a great job in fighting disinformation.

But Ingle stressed that even with the latest AI, it would be difficult to detect disinformation accurately.

“So you need both the algorithm, the AI, and you need people there as well to be kind of checking each other out to help each other,” she said.

The spread of harmful content is a serious issue in Japan, too. In fiscal 2022, the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry’s hotline for reporting illegal or harmful content received 5,745 calls, more than double the number from 10 years earlier.

The ministry’s panel on platform services, chaired by Prof. Joji Shishido of the University of Tokyo, is cautious about government intervention due to freedom of expression concerns. The panel, which is studying measures to ensure safe online spaces, believes that disinformation should in general be tackled by the platform operators.

However, Meta, X and YouTube-owner Google did not respond to the panel’s inquiry about the structure of their departments in Japan that are tasked with accepting deletion requests. They also did not clarify how many times they disclosed information about people who made inappropriate posts.

In its report in August last year, the panel said that platform operators had not adequately ensured transparency or accountability.

“A certain institutional framework is needed to enhance the transparency of platforms,” Shishido said. However, before a framework is put in place, “Japan must seriously consider how to handle platform services.”

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Strait of Hormuz Closure Shakes Markets; Prolonged Closure Could ...

-

Iran Situation: Japan Must Exert Diplomatic Efforts without Merel...

-

Japan Traditional Puppet Performance Held at Onsen Resort in Shiz...

-

2 of Japan's Opposition Parties Submit Bill to Revise Political F...

-

U.S. Urges Citizens to Immediately Depart over A Dozen Middle Eas...

-

Chiba Police to Arrest Japanese National in Midair; Man Accused o...

-

Japanese Firms Ban Business Trips, Cancel Vacation Tours Amid Mid...

-

Trump Pursues Iranian Decapitation without a Plan for What Comes ...

Popular articles in the past week

-

Milano Cortina 2026: Japanese Gold Medalist Figure Skater Miura S...

-

Tokyo Spends Big on Children, Wins Over Parents

-

Japan’s Miura, Kihara Announce Withdrawal from Figure Skating Wor...

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Ch...

-

Yokohama to Test Out Renewable-Powered Offshore Floating Data Cen...

-

BOJ Keeping Eye on Economy and Takaichi's ‘Proactive Fiscal Polic...

-

Tokyo Measles Patient Traveled to Fukuoka Aboard JAL Planes; Susp...

-

Japan’s Takaichi Speaks on New U.S. Tariff in Upper House, Says P...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reco...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages C...

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Befor...

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far f...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All Evacuate Safely

-

Tokyo Skytree’s Elevator Stops, Trapping 20 People; All Rescued (Update 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan