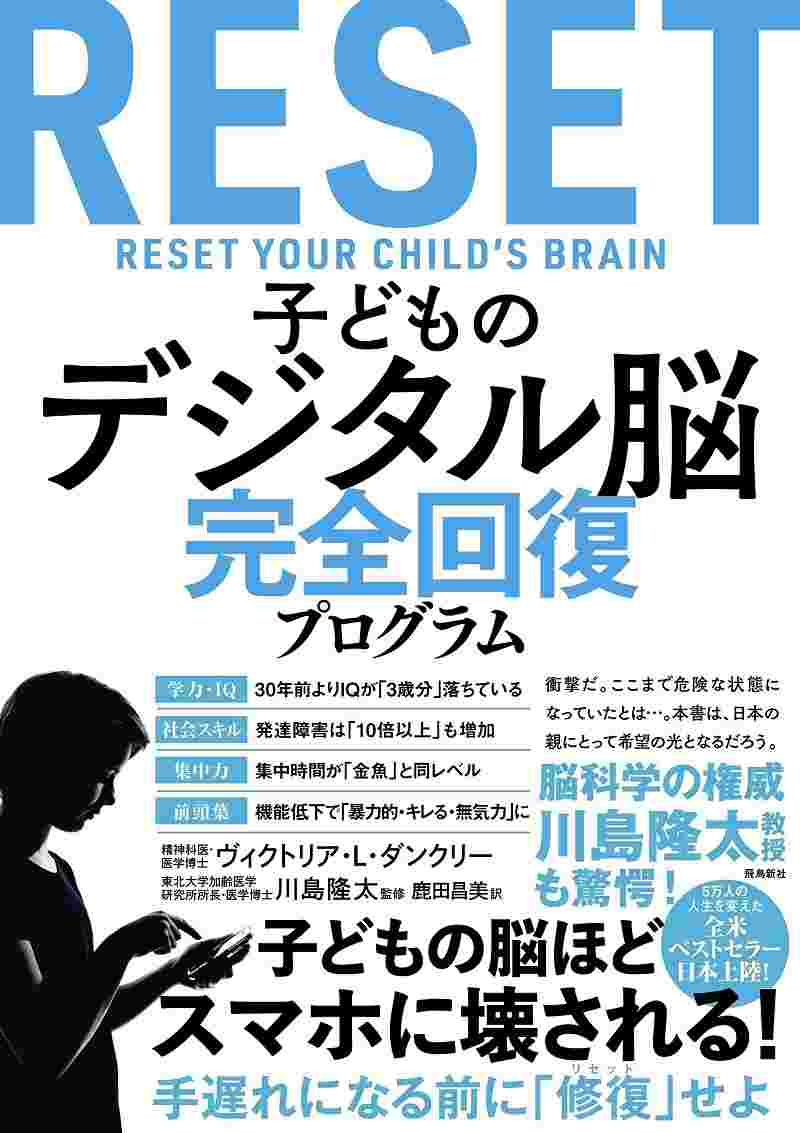

A Japanese translation of “Reset Your Child’s Brain” by Victoria Dunckley was published in May.

11:00 JST, September 29, 2022

Spending long periods looking at computer or smartphone screens has been linked to various physical and mental health issues. American psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley, 52, spoke to The Yomiuri Shimbun about the impact of information technology in schools, the digitization of textbooks and what she calls “electronic screen syndrome.” The following excerpts from the interview have been edited.

The Yomiuri Shimbun (Q): What happens when children spend too much time looking at screens and what is electronic screen syndrome?

Victoria Dunckley

Victoria Dunckley (A): When the nervous system goes into a state of overstimulation from too much screen time, children easily become irritated, cry, or go into “fight or flight” or “survival mode.” It looks different in different children, but this underlying hyperarousal is kind of what’s going on in all cases. They are kind of revved up all the time, and they are also exhausted at the same time. It is more serious with interactive activities such as games than with passive TV viewing.

When we look at physiology, we know that screen time alters brain chemistry. It desynchronizes the body clock. It raises stress hormones, both cortisol as well as the fight or flight hormones. It seems to shift blood flow from different parts of the brain including the frontal lobe. We know that brain imaging studies show that too much screen time actually damages the brain and causes changes in the gray matter and white matter. And it actually makes the cortex thinner.

It makes sense that the brain is responding to all this stimulation. And if that’s the case, and all these systems are kind of out of whack, the only way to really correct it is to pull all that stimulation away completely by four weeks of digital detox, or electronic fast.

Q: Your 2015 book “Reset Your Child’s Brain” was a bestseller in the United States, and has been published in more than 10 languages, including French, Russian, Chinese and Japanese. What kind of response have you received since the book was released?

A: What was striking was how similar the issues are across the world. Everyone’s talking about the fact that kids are spending too much time in front of screens and that the pandemic made it worse. Everyone’s talking about remote learning in school and that they’re worried that it has gone way too far.

A few years back it was mostly parents and teachers who were interested in this topic. Now it’s therapists, physicians, pediatricians, and obviously the media who are very interested.

Q: How are digital devices being used in U.S. schools and what do parents think about the situation?

A: In the United States, some schools would give them the option. They could either have a Chromebook or they could choose not to have one. That’s the best way to do it. But most schools weren’t offering that. Other schools would offer the option of not having to use a computer based on parents’ requests.

Other schools were pretty low tech and it’s interesting to see that in Silicon Valley, parents are seeking out low-tech schools because they know how addicting everything is, and they know the research. That’s very telling. When I was looking at schools for my own son, I toured 15 or 20 schools in different districts, mostly public schools, and some charter schools. What I was finding was that there was a huge variation. Surprisingly, some of the schools that didn’t have the highest scores were more open to doing things in a brain-based developmental way. They were waiting to expose the kids to computer use until the later elementary years.

Other schools that were ranked very highly seemed to feel pressure to embrace technology and use it in every way possible. Those schools seem to feel pressure, especially since the pandemic, to keep using all this software to teach things like reading, math and spelling. And we know that doesn’t work. It’s not optimal. And even if it does work in some cases, it doesn’t mean it’s good for the child.

One charter school I interviewed said they recognized some kids were sensitive to screens. They had a group of kids who just didn’t do things on the Chromebook or the tablet so that those children didn’t feel left out. It doesn’t mean they had no computer, but they used one a lot less and that to me was the best way to approach it, especially for younger kids.

Q: Since April last year, elementary and junior high school students in Japan have each been issued a digital device for learning. What impact does prolonged screen time have on children’s physical and mental health? What about the effects on their learning?

A: What we know from the research is that schools that have the most screen time — the most computer use — actually perform the worst in standardized testing. We also know that the amount of screen time is correlated with mental health issues, obesity, sleep issues and falling grades. So I would expect to see more mental health issues and problems with learning in Japan.

Even if kids are using the devices appropriately, we know that laptops in the classroom are distracting. You can imagine for a child whose brain is not fully developed, they’re constantly getting pulled into things. And it’s very hard for them to suppress that impulse.

Some teachers are trying to use software to teach kids how to read. But we know that using computers for reading actually slows down reading development, and it slows down their ability to read deeply and make connections with the material.

I think the actual use of computers is making it harder to focus and to learn, retain and integrate the material. Even if smarter or more resilient kids can learn by computer, it doesn’t mean they should.

Q: Japan is moving forward with plans to digitize textbooks — English textbooks will be digitized in 2024. What do you think about the move?

A: We have schools here that have tried doing that and a lot of them have reverted back because it doesn’t work. There are always technical issues when accessing the material.

Two marketing things that these software companies say are that it’s going to save the schools money and that it’s going to allow instant updates. What’s happening is that it has actually become very expensive. The teachers are reporting that the updates that are supposed to be happening every one to two years aren’t happening, and a lot of the material is out of date or wrong. So they’re going back to paper textbooks.

I just want to reemphasize that reading is faster on paper, learning is deeper, and retention is better. We know that when children take tests, their scores are higher when they are learning from paper. All across the board in every way, paper is superior. There is a ton of research showing that reading from paper and from a book is much more effective than reading from a screen.

So even if it was the same, you would still be causing the child sleep issues, hyperarousal and all these other things. It’s just not worth it in so many ways.

Q: Some parents might say, to keep up in this modern age of IT, the earlier children start to use a computer the better.

A: I think the notion “the earlier the better” is really marketing rhetoric. It puts tremendous pressure on parents, schools, educators and administrators to have kids be tech-savvy as early as possible. But we know that tech skills are relatively easy to learn. They are made to be user-friendly. We know that kids can learn them very quickly. Even kids with disabilities can learn them quickly, as opposed to reading and math, which are a lot harder to learn.

When I was touring schools, some were teaching kids even in preschool and kindergarten on Chromebooks. And I could see by the time these kids were in first or second grade, they already had a hunchback, which is frightening.

So it takes a lot of knowledge about how screens impact the brain, and faith that your child is not going to be left behind. Push back against that pressure and realize your child is going to be OK if they’re not getting these skills shoved down their throat at an early age.

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan