Disaster Preparedness / ‘My Timeline’ Charts Recommended to Help People Prepare for Various Disasters in Advance

Right: Damage caused by torrential rains in Kyushu in 2020

11:51 JST, September 30, 2024

Record-breaking torrential rains have occurred in recent years, resulting in large-scale floods across the nation. It is recommended that individuals and families make “My Timeline” charts so that the steps to take for evacuation are determined in advance. Such charts help people quickly take action in the event of a disaster.

***

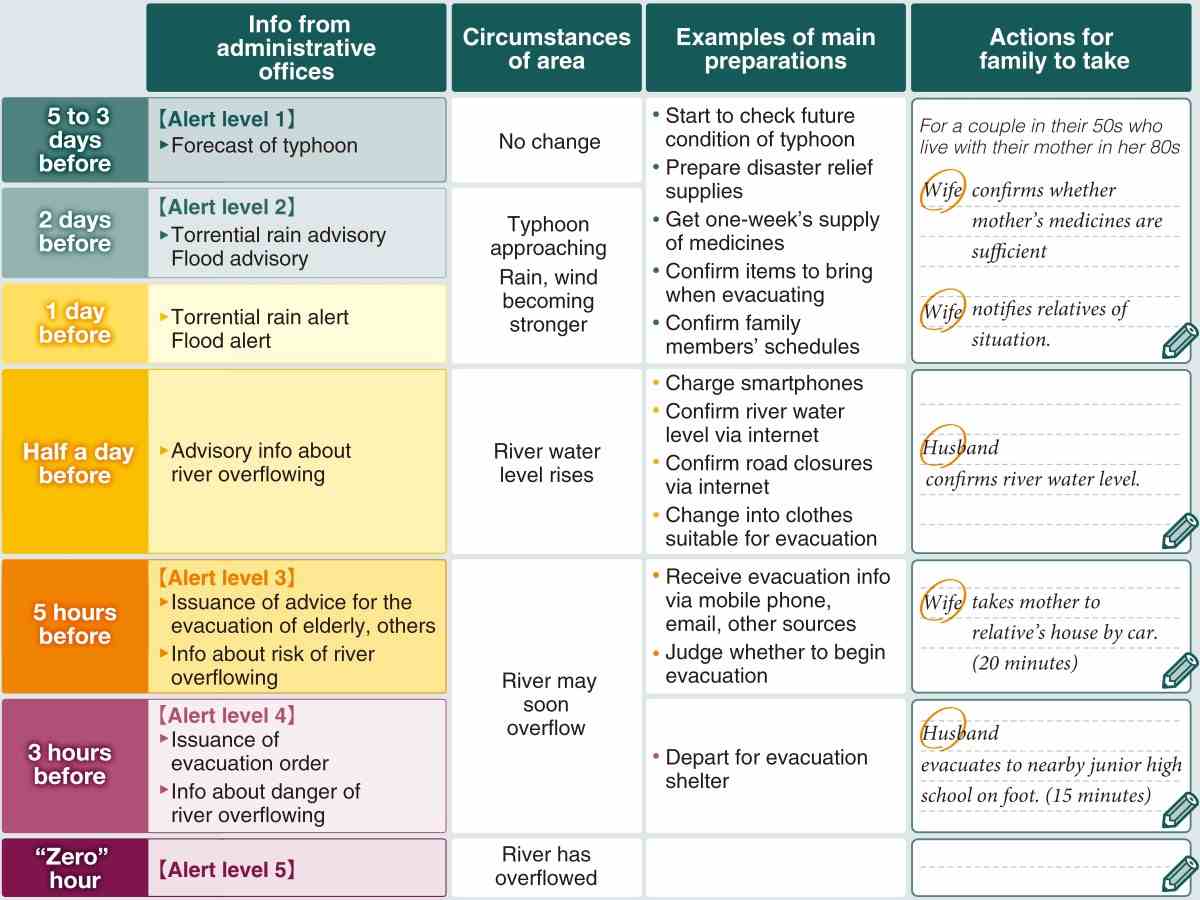

Use ‘My Timeline’ charts to prepare for disasters

Source: Documents of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry, others

■ Key points in chart creation

- Check flood disaster risks with hazard map, other means

- – Confirm assumed water depth in neighborhoods

- – Check information on geographical features, past floods

- Decide evacuation timing

- – Varies based on family makeup, such as having elderly, infants

- Confirm evacuation destination

- – Plans for upstairs of own house, relative’s house, shelter

- – Confirm available transportation means, time needed, route

■ Useful tools

Yahoo Japan’s Bosai Timeline website shown on smartphone

- Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry

- – Kit for elementary, junior high school students

- – Web Site (Japanese)

- Tokyo metropolitan govt

- – Sample of “My Timeline” digital version

- – Web Site (Japanese)

- Yahoo Japan

- – Provides Bosai Timeline function in Yahoo Bosai Sokuho info service

- – Web Site (Japanese)

- Local govts

- – Local govts nationwide introduce sample charts, other resources on respective websites

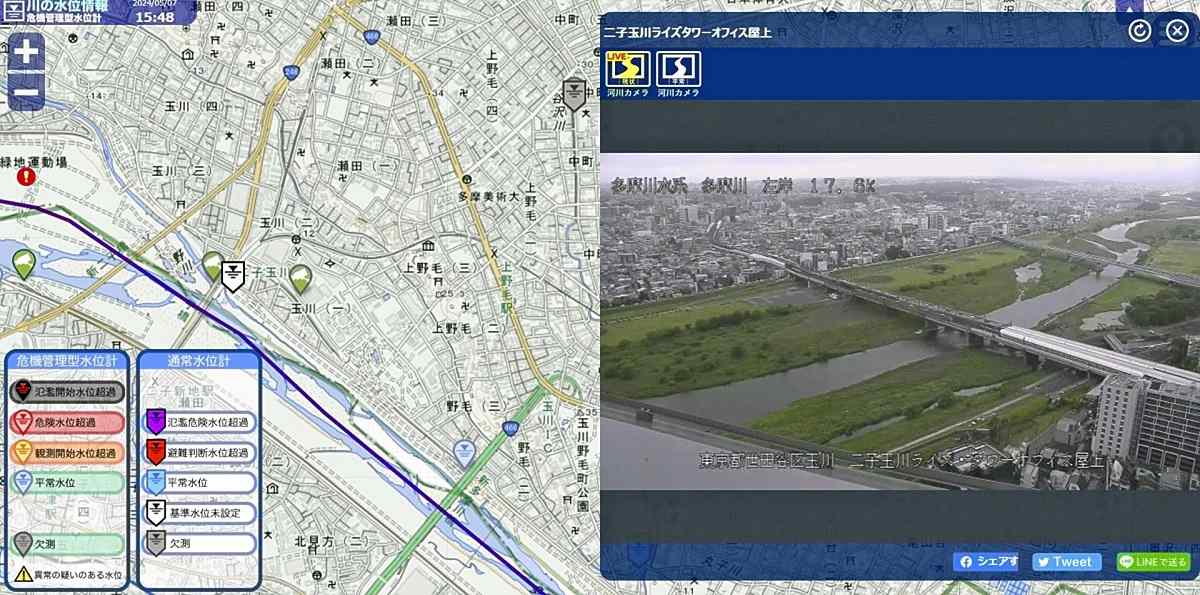

A website run by the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry indicates river water heights across the nation.

Family discussions on key points

The word “timeline” in terms of a disaster prevention plan refers to the actions to be taken by administrative authorities and others in chronological order, working backward from the occurrence of a disaster.

The U.S. state of New Jersey had formulated such a timeline prior to being hit by a hurricane in 2012. As the timeline proved helpful in the quick evacuation of residents, the method attracted attention, and initiatives to draw up these timelines also began in Japan.

“My Timeline” is a version of such a plan for individuals.

When heavy rainfall hit the Kanto and Tohoku regions in 2015, a levee of the Kinugawa River in Joso, Ibaraki Prefecture, was breached and about 4,300 residents failed to flee. They were rescued from houses and other structures.

In the wake of the incident, the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry’s Shimodate River Office, which covers the affected area, encouraged people to use “My Timeline,” and it posted on the internet tools for the dissemination of the method.

“People look at local governments’ hazard maps and other data, think about matters, talk with family members and hold discussions in the process of making a timeline,” said Prof. Naoya Sekiya, an expert of disaster information studies at the University of Tokyo’s Center for Integrated Disaster Information Research. “This results in sorting tasks and problems at the time of evacuation.”

According to the ministry, as of September last year, about 800 local governments nationwide made efforts to disseminate the method, such as by distributing samples of “My Timeline” charts.

By using the samples and guidebooks provided by local governments, it is easy to make such charts. People in many cases download forms on which they handwrite points.

Some local governments have built websites exclusively for this purpose, and people can easily make the charts on the internet using personal computers or smartphones.

Concrete details on necessary actions

When creating a handwritten chart, people input in chronological order weather information and evacuation information that the government has issued. They then write down actions that each family member needs to take in line with the information.

People need to write down necessary actions in a detailed manner depending on factors such as the locations of evacuation shelters, the timing of evacuations and disaster alert levels.

For example, when the alert level is 2 — meaning it is one or two days before a river may overflow due to a typhoon — the chart can serve as a reminder to confirm whether elderly family members have enough medicine.

In the process of making a chart, it is important to look at hazard maps, learn the levels of disaster risk and confirm data such as areas that may be flooded and the depth of flooding.

They need to consider how to evacuate in the most suitable manner according to the conditions. An evacuation destination plan includes whether they will evacuate to a relative’s house as soon as possible, evacuate to a shelter or move to the upstairs of their house as danger approaches.

Evacuation routes need to be decided by predicting which places may be submerged.

The timing for beginning to evacuate is different depending on the makeup of a family. For example, the timing differs depending on whether it is a weekday when one or two family members are not at home, or whether it is a weekend or a national holiday and everyone is at home.

So the chart needs to be filled out in such a way that the actions of each family member at the time of the disaster can be known.

If a family includes an elderly person, a pregnant woman or an infant, they should evacuate together with other family members when an order is issued to evacuate the elderly and others.

If people evacuate to a shelter on foot, they need to travel to the place during normal times to get an idea of how long it takes to get there at night, in the rain or under other circumstances.

Because people need to act in ways suitable to alert levels, they need to check in advance the nature of a disaster, geographical features of their neighborhood, what happened during past disasters and how to confirm the water level of rivers.

As the makeup of a family can change, Tadahiro Mukai, a senior official at River & Basin Integrated Communications, a Tokyo-based organization, said: “People should not think it’s OK to make ‘My Timeline’ charts once. I recommend that they review their charts regularly.”

Also used for tsunami, landslides

“My Timeline” charts can also be used for other kinds of disasters, such as tsunami and landslides.

It is predicted that tsunami waves will reach Kiho, Mie Prefecture, in about five minutes and 900 residents will die if a Nankai Trough megaquake occurs.

The town government created a timeline for flooding disasters in 2015. To further encourage residents to be better prepared for disasters, the town government last year made “My Timeline” charts for earthquakes and tsunami.

The chart defines the instance of the occurrence of a disaster as the “zero” minute, and indicates subsequent conditions as “tremors cease” about three minutes later and “arrival on uplands” about 10 minutes later.

Residents of the town can write their respective action plans that are the most suitable for their situations.

“It can be an opportunity for people in local communities and family members to discuss how to prevent or minimizing the damage caused by disasters,” said Katsuyuki Hori, chief of the town government’s disaster prevention section.

The city government of Fujieda, Shizuoka Prefecture, encourages residents to make “My Timeline” charts specifically for landslides.

There were cases in which evacuation alerts were not issued before landslides occurred. The city government aims to have residents maintain a higher sense of crisis so that they can evacuate based on their own judgment.

Some local governments recommend residents create “My Timeline” charts for landslides when they make ones for flooding, doing so as a set.

However, responses to disasters do not necessarily progress in line with prior assumptions.

People should regard “My Timeline” charts as only rough estimates, and it is important to judge and act flexibly while frequently confirming weather and evacuation information.

***

3/11 survivor perseveres ‘because there are people who care about me’

Dawn surely arrives after any dark night, however difficult the experiences a person has encountered in life.

Seietsu Sato holds a photo of his wife, Atsuko, on the Koizumi Coast in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, on March 11.

In the spring, which marked the 13th year since the Great East Japan Earthquake, I had such a thought when I reunited with Seietsu Sato, 72. He was formerly a firefighter and now lives in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture.

After retiring from his job upon reaching the mandatory retirement age, Sato has continued his activities as a storyteller of the disaster to inform others about the importance of disaster prevention.

Starting with many places across Japan, he has also been busy traveling to the United States and Taiwan, giving speeches more than 700 times.

In the seven years since I first got acquainted with him, I have gone to his speaking events as often as possible when they are held in Tokyo.

At the time of the disaster, Sato was a team leader at the Kesennuma Fire Department. In the city, which was devastated by tsunami and fires, he struggled to extinguish blazes and save people’s lives over the course of several days and nights.

One day after the March 11 disaster, he learned that his wife, Atsuko, 58, had gone missing. Later, her dead body was found on the Koizumi Coast near their home.

“Although I had repeatedly received training to save people, I could not save the life of my most loved one,” Sato said. Racked with remorse, he became reticent.

Why was he able to get back on his feet? I asked Sato that question, and he replied “It is because there are people who care about me.”

Since the disaster, many volunteers from other parts of Japan and foreign countries have gone to the devastated places.

Shortly after the third anniversary of Atsuko’s death, Sato gradually became able to talk about the disaster.

When Sato spoke about his memories of his late wife while shedding tears, everyone around him listened intently.

So, he made it his mission to tell others how important it is to prepare for a possible disaster during ordinary times so they can protect their loved ones.

Sato places particular importance on ties with other people.

He asked pianist Yuka Fujinami and cellist Yumiko Morooka, whom he became acquainted with through their volunteer activities, to hold a concert on March 11 this year. They held a charity concert in an elementary school in Kesennuma.

Sato, together with the children, listened to the sound of a requiem and prayer, and they mourned for the departed.

After the concert, Sato invited Fujinami and her fellow volunteer to his home. They enjoyed eating “azuki batto,” a regional specialty cuisine, and vowed together to continue to engage in future activities.

If Sato has friends who support him emotionally, he can reach the dawn. The shape that Sato now takes should be a source of hope for disaster victims nationwide who are suffering.

“I detest the tsunami that deprived me of my loved one,” Sato said, “but I learned the importance of stepping forward to a new goal.”

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan