Secrets of Kyoto / Oni: Dreaded Bringers of Plagues, Disasters; Demons that Captured People’s Imaginations

A monument built on a hill overlooking the village of Shuten-doji in Fukuchiyama, Kyoto Prefecture. From left: Shuten-doji pointing toward Kyoto, and his retainers Ibaraki-doji and Hoshikuma-doji

10:00 JST, August 26, 2024

Since ancient times, people in Kyoto have feared oni (demons), invisible beings that bring plagues and disasters. The “Wamyo Ruijusho,” a dictionary compiled in the mid-Heian period (794-late 12th century), explains that the word “oni” is derived from the ancient word “on,” which means “hidden thing.”

Oni gradually took on characteristics similar to Western depictions of devils.

At first, they were simply depicted as men with frightening appearances, but many people started imagining them with fangs and horns. Early depictions showed them wearing kimono, but this changed to have them be almost naked, wearing only a loincloth made of cloth or tiger pelts.

Many were also shown carrying a kanabo spiked metal club.

While no one has actually seen oni in real life, their depictions in paintings and other forms have frightened people over the years. This created a strong draw of people’s attention to the northeast, which was thought to be the kimon (demon gate) where demons come from.

Once oni were given shape, they started getting names as well. The most famous is Shuten-doji. “Shuten” means a drunkard. “Doji” originally meant “child,” but this oni was called “doji” because of its childlike bobbed hair.

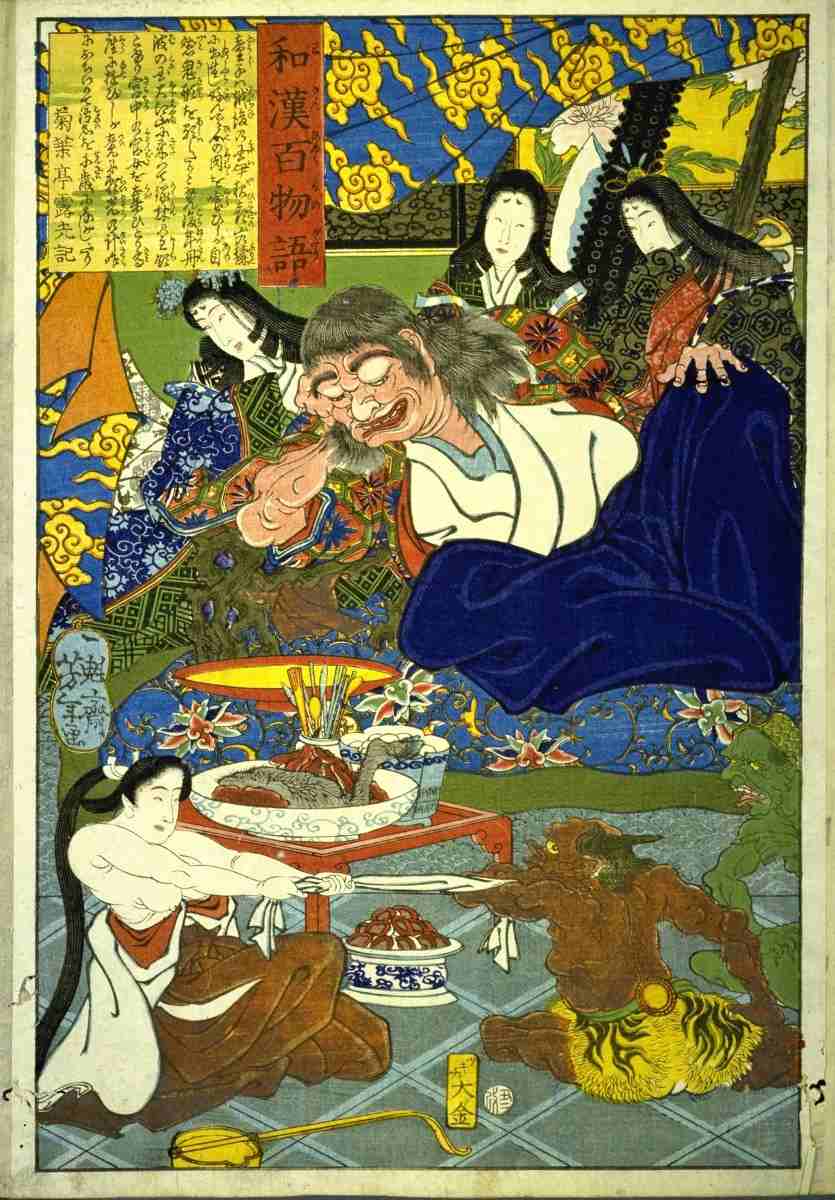

From his base in the Oeyama mountain range in northern Kyoto Prefecture, Shuten-doji often attacked Kyoto with a group of demons in his service. These oni looked like humans and, instead of bringing plagues and disasters, committed the same evils that humans do, such as abducting young women from noble families and stealing treasures.

Top: Statues depicting Minamoto no Yorimitsu and his retainer warriors on their way to defeat demons on the Oeyama mountain range, installed near the Japanese Oni Exchange Museum in Fukuchiyama, Kyoto Prefecture

Bottom: From right: Masks of Shuten-doji, his retainers Ibaraki-doji and Hoshikuma-doji at the Japanese Oni Exchange Museum in Fukuchiyama, Kyoto Prefecture

The emperor ordered a warrior named Minamoto no Yorimitsu to kill Shuten-doji. Yorimitsu and his retainers disguised themselves as yamabushi mountain ascetics and visited Shuten-doji’s base on Oeyama. They served paralysis-inducing poisoned sake to Shuten-doji and cut his head off.

This event took place in the 990s, which means that Shuten-doji was a contemporary of Murasaki Shikibu, the author of “The Tale of Genji.”

Two hundred years later, Minamoto no Yoritomo, a descendant of Yorimitsu’s younger brother, became the military leader of the country and established the Kamakura shogunate.

Some researchers believe that the story of Shuten-doji was written as an ancestral tale of victories which was commissioned by the Minamoto household, which replaced the nobility as rulers of the country.

The oldest existing story of Shuten-doji is the “Oeyama Ekotoba,” a picture scroll from the Nanbokucho period (from 1336 to 1392). The story was later made into the Noh play “Oeyama” and spread more among the people as the “Shuten-doji” story of the “Otogi-zoshi” collection of stories.

“Shuten-doji” from “Wakan Hyakumonogatari,” a series of ukiyo-e prints depicting legends by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Yorimitsu and his retainers tricked Shuten-doji and killed him. Some may wonder if this is a good ancestral tale to demonstrate the Minamoto household’s victories. But Japanese people have been accustomed to stories of victory through trickery since ancient times.

Yamatotakeru, a hero of the nation’s founding myths, was a prince of Yamato, which was based in present-day Nara Prefecture, who dressed as a woman and entered a banquet of the Kumaso king of southern Kyushu. He got the king drunk and stabbed him to death. It was a dastardly act, but this was how the Yamato rulers extended their domain.

There are several theories as to the true identity of Shuten-doji, including a foreigner, a descendant of those who defied the Yamato rulers, a mountain ascetic, a mine owner and a bandit.

Makoto Murakami, director of the Japanese Oni Exchange Museum located in the Oeyama mountain range, explained his own perspective by saying: “Demons are a reflection of our own minds, and Shuten-doji, who represents the demons, lives in everyone’s mind.”

From a replica of Kano Tanyu’s “Shuten-doji zu” (1730)

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

-

Senior Japanese Citizens Return to University to Gain Knowledge, Find New Career, Make Friends

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan