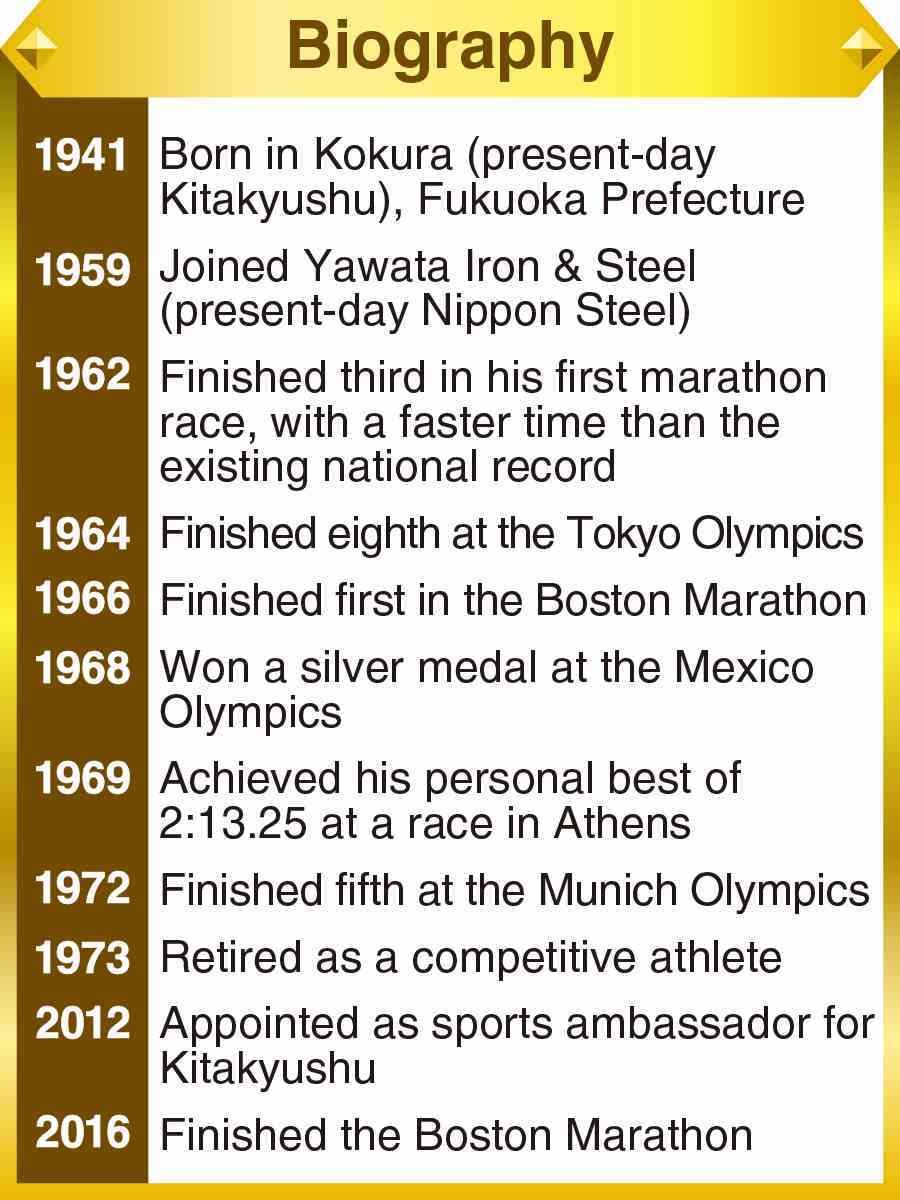

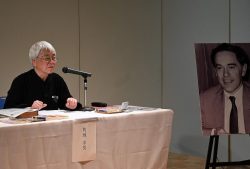

LEGEND / Kenji Kimihara: Running Opens Up New Paths in Life; the Legendary Runner Tells the Story of His Life

Olympic marathoner Kenji Kimihara speaks at his house in Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture, in May, saying, “Track and field allowed me to stand on the great stage of the Olympics, which I am proud of.”

16:00 JST, August 22, 2024

When running opens up new pathways in life

Kenji Kimihara has run 74 full marathons and finished all of them without dropping out. Running opened up a new path in his life. The legendary marathoner, who competed in three consecutive Olympics, starting with Tokyo in 1964, vows he will keep running marathons as long as he lives. At age 83, he is still light on his feet.

Though Kimihara calls his childhood the starting point of his career, he does not remember it as a wonderful time. He was good at neither studies nor sports. He never took the top spot in races at school sports days. “I was so bad academically that I was ashamed of myself. I just tried my best to avoid being humiliated,” Kimihara recalled. “I was a boy with no hopes or dreams, just a great sense of inferiority.”

Then, out of the blue, a major turning point arrived in his life. When he was a second-year junior high school student, a friend of his invited him to be part of an ekiden (road relay) club. “I did not have the courage to decline,” Kimihara recalled. So he joined the club. He had no particular interest in running, but all of a sudden he had begun his life as a track and field athlete.

Practice and training did little to improve his records, but when he was in his third year of high school, he took part in a 1,500-meter race at the national high school athletics championships. He did not make it to the final round. However, now that he had gotten to run in the national championships, he intended to quit track and field, “I was satisfied because there was now proof that I had played a sport,” he said. However, his academic performance remained poor, and he was not able to find a job. With graduation day approaching and pressure mounting, Kimihara unexpectedly found a way out.

The Yawata Iron & Steel Co., based in Kimihara’s hometown of Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture, had a strong company team but was seeking three more long-distance runners for a road relay race to commemorate the marriage of the then Crown Prince and Crown Princess. “By that time of year, there were no good runners left who hadn’t already chosen a career path. So, the offer came to me,” he said. He ended up continuing in track and field in exchange for a job.

Since the other members of the company team were top-level athletes, Kimi¬hara had difficulty even keeping up with practice sessions at first. Even so, he came to realize that he was truly a part of the team. Thinking he would not be able to run faster than the other runners if he kept doing the same things they did, he ran a lot. He practiced longer than the others and ran as far to the outside as he could when he ran around a track. Wanting to experience a marathon just once, he decided to participate in the 1962 Asahi International Marathon. Even though it was his first marathon race, he came in third, with a fast time that beat the existing national record. Suddenly, he had made his mark as a marathon runner.

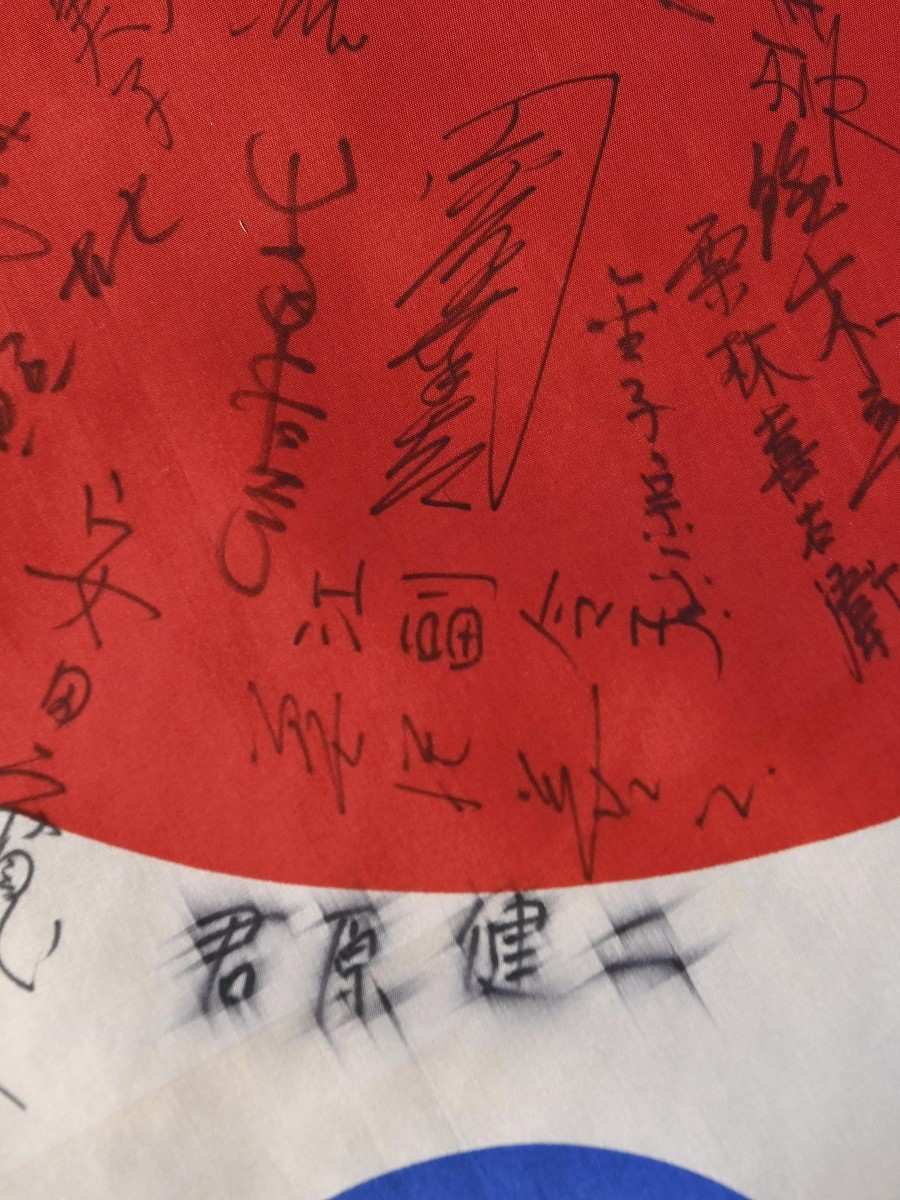

Part of a collection of messages from athletes who participated in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The photo shows the name of Kenji Kimihara in the bottom and the signature of Tsuburaya in the upper center.

After that, he continued to shorten his time, and he was selected to represent Japan as a marathon runner at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, along with Kokichi Tsuburaya and Toru Terasawa. Competing in a big event representing post-war Japan put Kimihara under heavy pressure. He came in eighth, with a time 3 minutes and 30 seconds slower than his personal best.

Until just before the start of the race, Kimihara had been watching other sporting events and collecting autographs from other Japanese track and field athletes at the Olympic village. This might have affected his performance. However, Kimihara accepted the results. After the Tokyo Olympics, he submitted a letter of resignation to the company, thinking, “I cannot run under such pressure anymore.”

He was allowed to take a leave of absence to rest. About a year later, his coach made him an offer. “The next Olympics will be held in Mexico. The venues are located at a high altitude, so the Japan Association of Athletics Federations wants to conduct some on-site tests to examine how that affects the human body. How about you join them?”

“I’ll get to travel to Mexico as a human guinea pig. I couldn’t ask for anything better,” he thought, so he accepted the proposal.

The silver medal Kimihara won in the marathon event at the Mexico Olympics.

He now thinks that the proposal was part of the coach’s strategy to get him back to competing. He was asked many times to continue to run in marathon races, and he was finally persuaded to fully return. He proceeded to finish first in the Boston Marathon, win silver in the men’s marathon at the Mexico Olympics and come fifth in the Munich Olympics, even as younger runners were appearing on the scene. He led the men’s marathon world as a reliable runner backed up by plenty of practice.

Originally, Kimihara did not like track and field. He was a boy who had a sense of inferiority because he had no special talents. Even so, he went on to be a world-class competitor. “An underachiever like me became an Olympic athlete. That means everyone has potential,” he said.

His most recent full marathon was the Boston Marathon in 2016, but he still runs in events and on special occasions with track and field lovers. He also runs in a park near his house.

“Helping other people makes me happy. My mission is to keep running as long as I can,” he said. For him, running is an essential reason for living.

Kokichi Tsuburaya, friend and rival

Kokichi Tsuburaya, the bronze medalist in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, was both a rival and a comrade for Kimi¬hara.

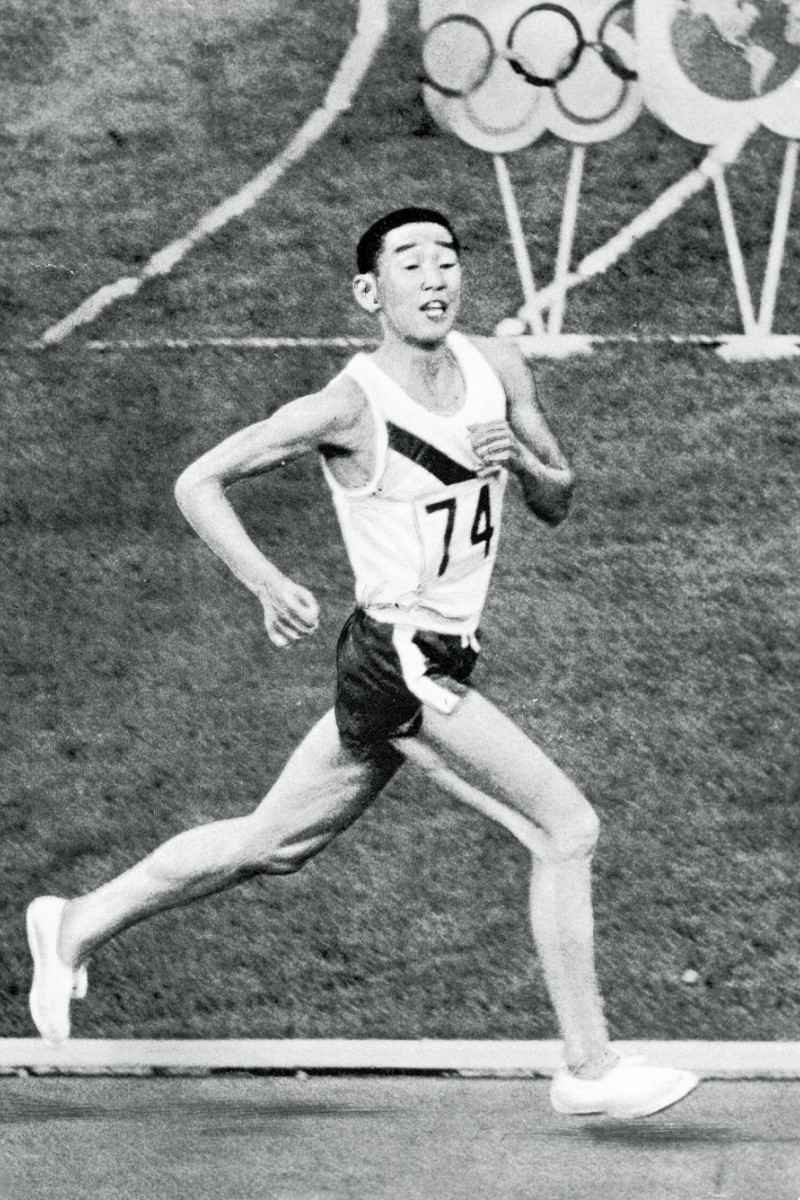

Kenji Kimihara runs on a track at the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City, en route to the silver medal in the 1968 Olympic marathon competition, on Oct. 20, 1968.

In January 1968, the year of the Mexico Olympics, Tsuburaya took his own life when he was just 27 years old. When Kimihara ran in the Olympic marathon that year, he was carrying his memories of his friend with him. Usually, Kimi¬hara never looked back during a race because this could throw off his rhythm. But this time he looked back to see behind him just before the finish line. Then he saw another runner picking up the pace, so he made a final dash. In the end, he won the silver medal.

At the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, Tsubu¬raya had finished third after being overtaken in the national stadium, where the finish line was located. Tsuburaya also stuck to the style of keeping his eyes to the front while running, and he reportedly regretted that he had been overtaken in front of many Japanese people. Kimihara said that he had looked back in the race at the Mexico Olympics probably because he felt “something like inspiration being sent down from Tsuburaya in heaven.” Kimi¬hara believes that his friend helped him in the race.

Now, participating in the Tsuburaya Kokichi Memorial Marathon in Sukagawa, Fukushima Prefecture, Tsuburaya’s hometown, has become Kimihara’s life’s work. Every time he participates in the marathon, he visits his friend’s grave. There, he opens a can of beer as he looks back on memories of a training camp in Hokkaido which he and Tsubu¬raya attended before the 1964 Olympics. At the camp, they drank together after both producing good records.

Kimihara ran through Sukagawa with the Olympic torch for the Tokyo Games in 2021. He carried a photo of Tsuburaya under his uniform and thought about his friend.

The Legend feature profiles era-defining figures in culture, sports and other fields.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

‘World’s Oldest Bio-Business’ Is Japan’s Seed Koji Retailing, Mold Used to Make Fermented Products like Sake, Miso, Soy Sauce

-

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts