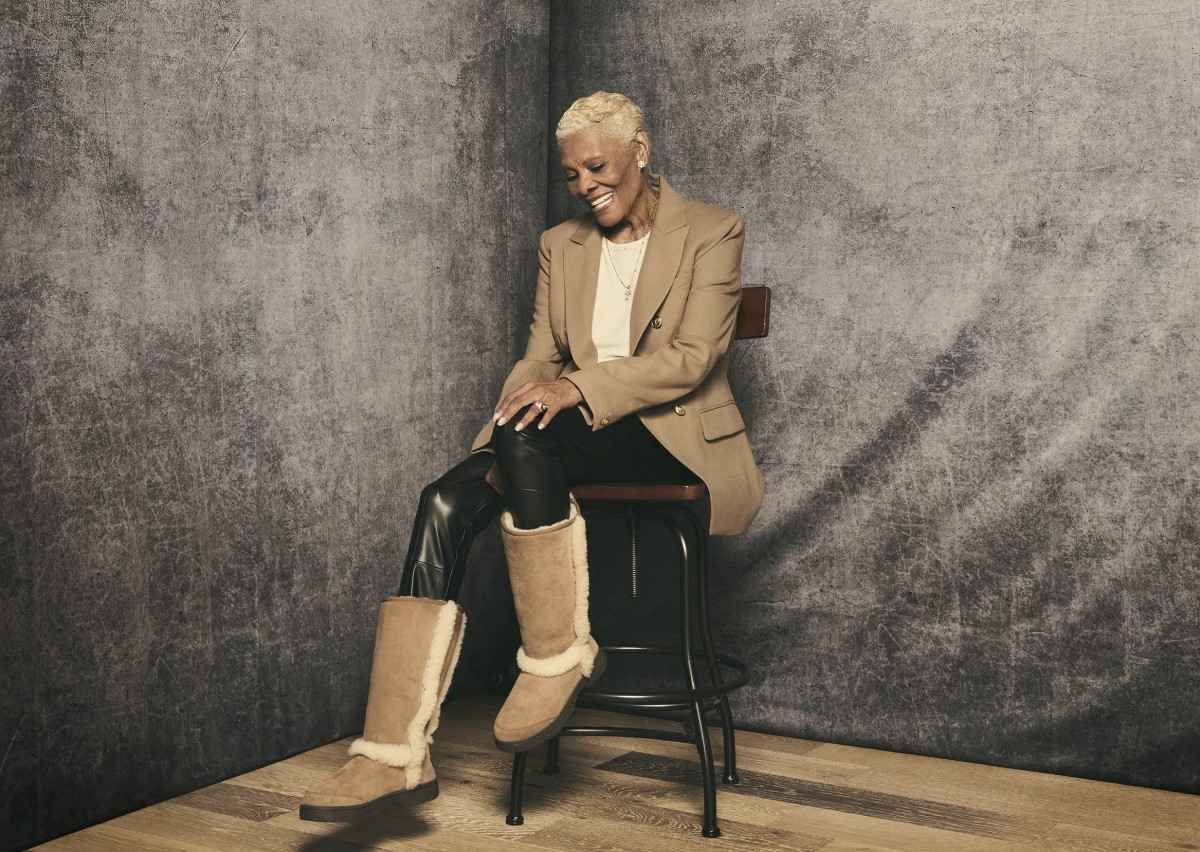

Warwick will be recognized Sunday at the Kennedy Center Honors for her lifetime achievements.

12:50 JST, November 29, 2023

NEWARK

It was in this city that Dionne Warwick learned to sing.

At 6 years old, she sang “Jesus Loves Me” while standing atop a pile of books at the pulpit of St. Luke’s AME Church, where her grandfather was a minister. She shares this origin story often, even opening her memoir with it. It marked the first time she performed at a service, and a moment of discovery that would lead to years of singing at the nearby New Hope Baptist Church.

Warwick comes from a musical family, maternal cousins with legendary opera soprano Leontyne Price and pop legend Whitney Houston, the daughter of soul and gospel singer Cissy Houston. Warwick made it to the big leagues early in life, first singing backing vocals and, in her 20s, recording demos for songwriters Burt Bacharach and Hal David before landing her own record deal. She spent years in California. She toured the globe, selling more than 100 million records worldwide.

But New Jersey remained close to her heart. She moved back and, at 82, still lives here.

“I don’t know if there’s any reason left for me to leave,” she says matter-of-factly on an October afternoon at the Newark Museum of Art, located mere blocks away from the New Hope Baptist Church.

She exudes pragmatism. Passion and determination are trademark characteristics of her famous family. She would say she gets it from both sides. Before she sang at that pulpit, her paternal grandfather, the Rev. Elzae Warrick, whispered to her, “If you can think it, you can do it.”

And so she did. Warwick will be recognized Sunday at the Kennedy Center Honors for her lifetime achievements. That includes her musical hits – “Don’t Make Me Over,” “Walk On By” and “I Say a Little Prayer,” to name a few – as much as it does the legacy she continues to build. Warwick is still putting out new music and has attracted a new generation of fans online, where her cheeky presence on X (formerly Twitter) has in recent years earned her a reputation as the internet’s auntie.

Online, she raises an eyebrow at youthful lingo but quickly learns to embrace it: To someone bold enough to refer to her as a “snack,” she responded, “I just learned what this meant. Thank you. Lol.” In May, amid changes in Twitter’s leadership, she joked she was “excited to officially take on the role as CEO.” Just two months later, she posted, “I am resigning from this position. They’ve got too much going on here.”

Warwick dispenses the sort of hard-earned wisdom her grandfather once shared with her. She speaks with conviction. Whenever she has shared the news of her upcoming honor, she says, people have responded the way she would, too: “It’s about damn time.”

Meeting at the art museum was her idea. She appreciates its embrace of her community. Waiting for her to arrive, I chat with Glenn Mason, a charming security guard who recalls seeing Warwick perform at the Garden State Arts Center back in 1970. He attended church with her Aunt Cissy and remembers little Whitney, then known by the nickname Nippy.

Soon after entering one of the museum’s “Seeing America” galleries, Warwick removes her jacket to reveal a T-shirt adorned with a dark-skinned Betty Boop cartoon labeled “the original.” She sits upright at the edge of a couch, poised and ready to chat about her diligent work ethic and defiance of genre, stopping here and there to reflect on her life story.

Marie Dionne Warrick was born in 1940 to Pullman porter Mancel Warrick and Lee Drinkard Warrick, who worked at an electrical plant. (The “Warwick” spelling comes from a typo on her debut record.) After his retirement, Mancel became an accountant and record promoter. Lee managed the family gospel group, the Drinkard Singers, in whose footsteps Warwick and her sister, Dee Dee, followed.

According to Danyel Smith, author of “Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop,” the Drinkards are “one of the most unheralded musical powerhouse bloodlines in the history of American music.” Among all that talent, Warwick still stood out. Bacharach asked if she would record demos after hearing her sing backup in 1961 for the Drifters. The composer, who died in February, said in the 2021 documentary “Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over” that she “had this huge range.”

“She’s very delicate, and then she’s very explosive,” he said, noting the rareness of that ability.

The film gets its name from Warwick’s 1962 single, which Bacharach and lyricist Hal David wrote after she came to them upset that the duo had given another artist the song she wanted for her solo debut. They borrowed her phrase, “Don’t make me over.” Set to a waltz tempo, Bacharach’s tight arrangement lays the ground for Warwick to sing the line with sweet precision. She floats back and forth between delivering the firm command and crooning desperate pleas, as written by David: “Don’t make me over/ Now that I’d do anything for you/ Don’t make me over/ Now that you know how I adore you.”

Warwick’s impassioned warble figures into many collaborations with Bacharach and David, a reminder of the vulnerability that lies beneath even the most compelling displays of fortitude. In 1964’s “Walk On By,” she protects her “foolish pride” by asking a former lover to look past her visible grief, singing the titular lyric with a lilt. In the more playful-sounding 1968 track “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” Warwick’s careful vocals imbue the story of a San Jose native – who returns to her hometown after failing to make it in Los Angeles – with the subtle humility of someone seeking to steady herself again.

The author Smith argued that Warwick remains “wildly under-credited” for the vocal arrangements of her work with Bacharach and David (a relationship that hit a snag in the 1970s, when she sued them for breach-of-contract issues, but that eventually righted its course). Warwick’s most valuable asset has always been her command over her voice, whether while performing or in her advocacy work.

In 1985, Warwick reunited with Bacharach for a cover of “That’s What Friends Are For” to benefit the American Foundation for AIDS Research at a time when such prominent efforts were few and far between. The song, credited to “Dionne & Friends,” also features Elton John, Gladys Knight and Stevie Wonder. Warwick simply asked the superstars to take part. All three agreed.

“It was serendipitous,” Knight said in an email. “Dionne called me and told me I should come over and do this song with her and, of course, I did – who says no to Dionne?”

At the museum, Warwick is cut off mid-sentence by her phone ringing. It blasts the jubilant chorus of “I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me),” and Whitney Houston’s voice echoes through the room. Warwick picks up: “I can’t talk right now,” she says, immediately hanging up to return to her story.

Warwick has faced great tragedy, and grieved in the most public of arenas. Her faith and productivity keep her grounded. She has referred to her family’s musical legacy as “preordained” and tends to limit discussion of Whitney to the enduring impact of her work. Oh, that beautiful voice.

In East Orange, N.J., Warwick and her siblings grew up with a vibrant sense of community. She wrote in her memoir that their neighborhood “resembled the United Nations.” They were taught to carry themselves with grace and an open mind. Warwick maintains to this day, “I lived a normal life. And still do.”

Despite her high-profile career, Warwick tried to provide her two sons with a semblance of that “normal life.” David and Damon Elliott were each born during Warwick’s second marriage to William Elliott, the actor and musician she married in 1966, divorced and remarried in 1967, then divorced again in 1975. (She said years later, “It’s hard when the woman is the breadwinner.”) In the 1990s, when Warwick wasn’t recording, she did infomercials for the Psychic Friends Network to make ends meet.

That wasn’t the only time Warwick fell into financial trouble; she filed for bankruptcy in 2013, when her lawyer blamed the hardship on “a business manager who mismanaged her affairs” back in the ’90s. She prioritized her family all the while, according to Damon, a record producer who has worked with artists such as Destiny’s Child, Solange, Pink – and Warwick herself. He remembered his mother’s vigilance during a period of junior high when he was acting up at school while she was on tour in Europe.

“I don’t know how she did it, because she had left the day before,” he said. “She popped up the very next day and caught me trying to ditch. I’ll never forget that. She always said, ‘I’m right around the corner.'”

Warwick waves off the question of whether there are any contemporary artists she admires. She largely listens to her peers. She has maintained strong friendships with some – “I don’t recall a time we weren’t in each other’s lives,” Knight said – and is still recording with others. In February, she and Dolly Parton released the gospel duet “Peace Like a River,” written by Parton and produced by Warwick’s son Damon. Warwick smiles big as she shares her excitement over an upcoming collaboration with Earth, Wind & Fire, whom she considers to be her favorite group of all time.

During the pandemic, Warwick’s great-niece Brittani Warrick, a creative director, encouraged her aunt to spend more time on Twitter. Warwick’s off-the-cuff remarks quickly attracted a bigger following. In December 2020, she tweeted, “Hi, @chancetherapper. If you are very obviously a rapper why did you put it in your stage name? I cannot stop thinking about this.” He responded in awe that she knew who he was. She replied, “Of course I know you. You’re THE rapper. Let’s rap together. I’ll message you.” And so came to be their duet, “Nothing’s Impossible.”

“It’s who she is as a person,” Warrick said of her aunt. “If you were to talk to her on the street, that’s who she is. She’s hilarious. . . . It’s endearing, but she’s not afraid to clap back at somebody.”

“Saturday Night Live” took notice. In December 2020, the show aired its first sketch featuring cast member Ego Nwodim as host of the fictional “Dionne Warwick Talk Show.” Adopting the singer’s raspy speaking voice, Nwodim’s Warwick struggles to identify her guests, whether it’s Harry Styles (played by Timothée Chalamet), Billie Eilish (Melissa Villaseñor) or Machine Gun Kelly (Pete Davidson), whose edgy, tattooed presence she immediately shoos away. The sketch pokes fun at Warwick’s indifference toward younger celebrities – though Warwick might since have changed her tune, posting in October, “I love these newcomers and their stage names. What does Ice Spice mean?”

Nwodim first attempted to emulate Warwick at the encouragement of castmate Heidi Gardner, who, like everyone, was delighted by the singer’s new hobby. Nwodim could do a decent Maya Angelou impression and sensed tonal similarities in their speaking voices. “I bet I could do a Dionne Warwick,” she recalled thinking at the time, noting that “there’s a sort of musicality to the way she speaks.” The comedian worked with SNL writers Anna Drezen and Alison Gates to mimic Warwick’s topical humor.

Nearly a year later, Warwick commuted across the Hudson River to 30 Rockefeller Plaza and made an appearance on the fake talk show. In the sketch, she walks onto the stage in a glittery tracksuit and sits in an armchair opposite Nwodim. “Hello, darling,” she says. “I’m so excited for you that I’m here.”

“It was surreal,” Nwodim said. “I still don’t believe it happened.”

Warwick has grown to accept her flowers in whatever form they are given, tweeting after the initial sketch, “That young lady’s impression of me was very good.” Decades after winning Grammy Awards in both the pop and R&B categories, she notes that she has also earned praise as a jazz, rock and even opera artist. She doesn’t mind the categorization, as “the same eight notes are used in each one of those areas.” All that matters to her is that she knows her own path forward.

“God said, ‘This is what you’re going to be doing,'” she says. “So that’s what I’m doing.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan