Members of Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), a grass roots organization led by formerly incarcerated people, meet on Nov. 2, 2022, in New Orleans.

16:12 JST, January 2, 2023

BATON ROUGE – Breakfast at Louisiana’s state Capitol includes fresh coffee, cookies and egg sandwiches – made and served in part by incarcerated people working for no pay.

Inmates Jonathan Archille, left, and Brodarius Washington, at the cafe in the Capitol building in Baton Rouge.

“They force us to work,” said Jonathan Archille, 29, who is among more than a dozen current and formerly incarcerated people in Louisiana who told The Washington Post they have felt like enslaved people in the state’s prison system.

Archille said prison staff had even used that term against him. “You’re a slave – that’s what they tell us,” he said. A spokesman for the Louisiana Department of Public Safety & Corrections, Ken Pastorick, said it “does not tolerate” such language and is looking into the allegation.

In the 2022 midterm elections, voters in four states approved changes to their constitutions to remove language enabling involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime – part of a larger push for change that many say is long overdue. But in Louisiana, a ballot measure that was conceived with the same goal in mind was rejected by a nearly 22-point margin.

Some observers and proponents of the Louisiana amendment attributed the result to the convoluted wording of the ballot question, which was changed to appease Republican lawmakers. Others said the measure wouldn’t have passed in its original form because the state was not ready to upend labor practices in its prisons.

“The drafting of our language didn’t turn out the way we wanted it to,” said state Rep. Edmond Jordan, a Democrat who sponsored the bill to change Louisiana’s constitution before later urging people to vote against the ballot measure that would have ratified it.

The amendments that passed in other states aren’t expected to lead to immediate, dramatic changes, which would require further legislation or legal challenges, and it’s unclear what would have happened had the more muddled Louisiana measure won approval. But the result is an unsettled debate in a state that has one of the highest incarceration rates in the country – and one that encapsulates broader themes such as race, criminal justice and the history of a country where slavery was once legal, all of which are at the center of the endeavor to revise other laws and regulations across the country.

Advocates are pushing for more state constitutional changes in upcoming elections, saying they are fighting for greater protections in a system that disproportionately affects Black and Brown people and forces many people to work for little or no pay. There are campaigns in about a dozen states, including Florida, New York and Ohio, for similar ballot measures in 2024. And the question could return in Louisiana in 2023.

As many as 800,000 incarcerated people work in prisons across the country, providing more than $9 billion a year in services to those facilities and creating around $2 billion in goods and commodities, according to a study from the University of Chicago’s Law School and the American Civil Liberties Union. The average prison wage is 52 cents an hour, while seven states are not required to pay prisoners for work. Many spend half their earnings on taxes and accommodation, the research shows.

“Louisiana law mandates that state inmates, necessarily serving a felony conviction, are required by law to work while incarcerated,” said a statement from the corrections department provided by Pastorick after the ballot measure was voted down. “Each inmate who is capable of working, is assigned a job duty, which may include working for the prison, or for Prison Enterprises.”

Prison Enterprises is a for-profit arm of Louisiana’s corrections department, which sells items made by prisoners, including office furniture, mattresses and offender uniforms.

“State law also provides that inmates ‘may’ be compensated, and state law also sets the range of an inmate’s earnings according to the skill, industry, and nature of the work performed by the inmate and shall be no more than a dollar an hour,” added the statement provided by Pastorick.

***

A glimpse of Louisiana’s system came into focus last November at the Capitol building in Baton Rouge. Inmates arrived early each morning from Dixon Correctional Institute dressed in khaki shirts and green trousers; prison uniforms that have numbers sewn onto the breast. Some grabbed mops for janitorial work, others started hauling furniture. A few, including Archille, headed to the Louisiana House Dining Hall.

Archille was sent to prison when he was 17 after being found guilty of attempted murder for shooting two people from a car, according to court records. He has spent three of his 13 years in prison working at the Capitol on the “Trusty” program, which gives incarcerated people who show good behavior the chance to work outside prison grounds. As a trusty, Archille doesn’t earn or touch money; customers are forbidden from giving him tips.

“How you doing ma’am, how can we help?” he said to one as he served meatloaf and collard greens. Archille said few visitors to Louisiana’s Capitol ask him questions about his prison uniform. He said he serves them with a polite smile and tells them to have a good day.

Archille’s colleague and fellow inmate Brodarius Washington, 26, also part of the Trusty program, said working in the cafe at the Capitol is “good because we’re dealing with people. But we don’t get paid and they work us a lot.” They described being forced to work and not having a choice in their job.

As they talked to a reporter, Washington and Archille looked over their shoulders at the cafe’s manager, expressing fear of repercussions. “They should at least pay us and not try to punish us for talking to people like yourself,” Archille said. “But I’m really not afraid.”

Pastorick said it is against state law to abuse an inmate and that the department does not retaliate. He said “there are appropriate channels for requesting inmate interviews.” He previously declined a request from The Post to visit Louisiana State Penitentiary and interview people there.

In response to Archille’s allegation of being called a slave, Pastorick said, “This is the first time we have been made aware of this allegation as the inmate did not alert our staff to the alleged incident.” He added that Archille did not provide information to further the prison’s investigation of the allegation. Archille said he had given the guard’s name earlier but that no action was taken.

A week after The Post sought comment on the matter, Archille’s mother said she hadn’t heard from her son for a couple of days. Upon inquiring further with prison personnel, she said she had been told her son was on “lockdown” in the prison while under investigation for speaking to a journalist, which included isolation and loss of certain privileges.

“I usually speak to him every day,” Archille’s mother said through tears. Like others, she spoke on the condition of anonymity because she feared for her safety. “They said they didn’t want him talking to you guys and that’s why he’s on lockdown.”

When asked for comment, Pastorick said over the phone, “If somebody violates a policy then there are consequences for violating that policy. Disciplinary actions happen. I don’t know what you’re talking about, I haven’t been in contact with the prison. This is the first I’ve heard of any such thing.” He did not respond to follow-up emails and phone calls seeking more clarity on the inmate’s status or specific rule violations.

In Louisiana, there were more than 27,000 people imprisoned at the end of October 2022, according to the state’s corrections department. A 2022 report into captive labor from the University of Chicago and the ACLU found incarcerated people in Louisiana’s prisons earn 2 cents to 40 cents an hour. Costs inside the prisons can be high by comparison, with a visit to the prison doctor costing $3, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. Pastorick said routine sick checkups cost inmates a $1 co-pay, while emergency visits cost $2. Fees are waived if they have less than $250 in their account, Pastorick said.

At Louisiana State Penitentiary, known colloquially as Angola, incarcerated people clean the prison, cook for fellow inmates, farm vegetables for the corrections department, help sick people as orderlies in the prison hospital, and care for hospice patients.

“Most of the [prison] facilities are operating with less than half of what their own experts have found is the minimum necessary to safely operate the facilities,” said Lisa Borden, a civil and human rights lawyer at SPLC.

Situated on 18,000 acres of land – greater than the size of Manhattan – the prison started as a plantation and derives its nickname from the country in Africa once associated with the slave trade. Today, around 74 percent of the more than 5,000 inmates at Angola are Black, according to the University of Chicago and ACLU research. Advocates for change say a line can be drawn from Angola’s foundation as a plantation to the fields where incarcerated people work today.

“I was a 16-year-old kid who went straight from the classroom to the cotton field,” said Terrance Winn, 49, who gave testimony to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination for its 2022 U.S. review about his time at Angola from 1982 to 2020. Describing guards on horseback who oversee the field, he added, “You actually experience and feel what slavery was like for our ancestors.”

Those who refuse to work at Angola can be sent to segregated housing, beaten, and denied visits with family, according to the University of Chicago and ACLU report. In the summer months, temperatures can exceed 115 degrees – but work continues, people formerly incarcerated at the prison said.

Pastorick said these claims about prison conditions were “unfounded” and the use of segregated housing is determined by a department rule book for offenders.

***

In recent years, there has been a growing movement to change state constitutions to prevent forced labor – part of a wider push to “End the Exception” in the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States.”

When Jordan proposed an amendment to Louisiana’s constitution in 2021, it was voted down in a committee due to Republican resistance. State Rep. Alan Seabaugh (R) described it as “dangerous,” and his colleagues voted to reject it.

Given that some felony convictions in the state come with sentences including imprisonment “at hard labor,” Seabaugh explained, people must work while incarcerated. “If you’re going to say a sentence with hard labor is tantamount to indentured servitude, and you outlaw indentured servitude, then you have potentially just invalidated” them, Seabaugh said.

In 2022, Jordan brought back the bill to amend the state constitution, which reads, “Slavery and involuntary servitude are prohibited, except in the latter case as punishment for crime.” Jordan wanted to strike the words “except in the latter case as punishment for crime.”

But state Rep. Richard Nelson (R) suggested an addition – clarifying that the law “does not apply to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice,” which he said would make it more palatable to his fellow Republican colleagues.

“We changed it to be like Utah, which everybody agreed to,” Nelson said. Voters in Utah approved a change to their state constitution in 2020 that removed the slavery exception but contained this provision to protect prison labor. Nelson added his amendment would still allow for work release programs, while removing the exception to slavery.

Jordan and Seabaugh both accepted Nelson’s amendment, which was cleared to go to a public vote. A nonpartisan member of staff in the state House drafted language for the ballot measure in the same meeting, which read: “Do you support an amendment to prohibit the use of involuntary servitude except as it applies to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice?” The use of the word “except” created complications.

After lawyers warned the measure could in fact be interpreted by courts to extend labor in prisons, Jordan reversed himself, telling people to vote “No.” Others followed Jordan’s lead and told people to strike down the measure, including the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus.

But Decarcerate Louisiana, an organization of formerly incarcerated people who proposed the constitutional amendment to Jordan, urged people to vote “Yes,” saying the bill would have improved the situation for people in prison.

“The ballot question was too confusing,” said Curtis Ray Davis II, the founder of Decarcerate Louisiana. “We didn’t understand what we were voting for.”

Jordan said the wording of the ballot measure, which passed without question, was a “mistake.” He said he did not believe the drafting was “an intentional effort to derail it.”

Robert Singletary of the Louisiana House Legal Division said nonpartisan staff drafted the ballot language, but he declined to comment further.

Fox Richardson, who was imprisoned alongside her husband Rob and has co-written a forthcoming book with him about their 21 years separated by prison, said she believed the amendment would reaffirm the exception and allow forced labor in prisons to continue. “I voted no,” she said.

Fox Richardson and her husband Rob Richardson in their New Orleans home on Nov. 3, 2022.

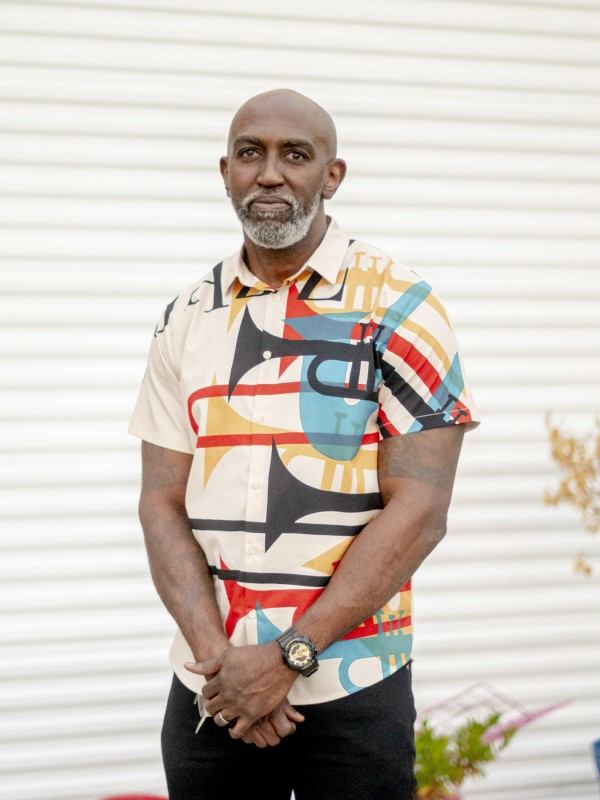

Ronald Marshall before the VOTE meeting in New Orleans, on Nov. 2, 2022.

Ronald Marshall and Bruce Reilly at VOTE, an advocacy organization for current and formerly incarcerated people, reflected the conflicting sides, with the former voting against it and the latter voting for it.

“It should have read ‘slavery and involuntary servitude is prohibited’ and left it like that,” said Marshall, who served 25 years at Angola and described a brutal time inside with heat exhaustion and workers sustaining debilitating injuries.

The language on the ballot measures in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont was more straightforward, with Alabama voting as part of a larger package to remove racist language from the state constitution and Vermont choosing “Yes” or “No” on prohibiting slavery and involuntary servitude.

Some advocates of change said even these outcomes do not go as far as they would like. “The [Alabama] measure prevents the state from forcing individuals into that type of work,” said Jerome Dees, policy director for the SPLC who specializes in Alabama. “What it does not do is prevent them from hiring out those individuals and unjustly compensating them.”

But others said the constitutional changes could open a path for lawsuits from incarcerated people who claim their constitutional rights have been violated. In Colorado, which was the first state to change its constitution in this way in 2018, two incarcerated people have brought a class-action lawsuit against Gov. Jared Polis (D). Colorado also passed a law that will give incarcerated people in the final year of their sentences a minimum wage of $12.56 per hour when working for private companies.

Amendments similar to the ones that appeared on ballots this year could appear in eight states next year, according to Davis. “Human beings should not be property of other people or entities,” he said.

In Louisiana, Davis said he hopes Jordan will bring the bill back to the legislature next year with improved language. If he does, Seabaugh said he will oppose it.

“We put too many constitutional amendments to the people of Louisiana,” Seabaugh said.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan