Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Successor Preserves Traditional Japanese Sweets with New Ingredients

Takeshi Kondo sprinkles coconut sugar on cacao beans after draining the syrup from them in his shop in Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto.

2:00 JST, December 15, 2025

KYOTO — Cacao beans with a thick coating of mitsu sugar syrup shine like jet-black gemstones.

Torokuya is a shop specializing in the sweet, called amanatto, in the Mibu district of Kyoto’s Nakagyo Ward. Although amanatto literally translates to “sweet natto,” the product is a type of wagashi traditional Japanese confectionery. It is usually made from beans, such as azuki red beans and black soy beans, which are simmered or coated in syrup and then dried.

Takeshi Kondo, the 35-year-old fourth-generation owner of Torokuya, lifted the coated cacao beans from the container in his store and sprinkled coconut sugar over them. The finished cacao bean amanatto had a rich flavor similar to dried fruit.

“It pairs well with red wine or whisky,” Kondo said.

You may also like to read

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Wagashi Confectioner Adds Playful Creativity to Traditional Techniques Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Brush Dyeing Artisan Searches for Perfect Color, Bluring Horizon Between ColorsThe product is from Kondo’s Shuka brand, which launched in 2022. The brand focuses on “enjoying nuts and beans” by using the traditional preservation method of coating ingredients in syrup. Shuka makes use of ingredients that are not traditionally preserved with this method, such as cacao beans, pistachios and cashew nuts.

The beans and nuts are boiled first and then coated in syrup. Next, they are sprinkled with sugar and dried. Although the process is simple, the sugars used are carefully selected, including sugar from beets grown in Hokkaido and wasanbon sugar produced in Tokushima Prefecture. The shop’s heating method makes the finished products firmer than standard soft amanatto and enhances their texture.

Shuka brand products, from left: toroku bean, super green pistachio, mizuho dainagon azuki bean, Tanba black soy bean, cashew nut and cacao bean

“One of the appeals of amanatto is that it maintains the shape and color of the ingredients,” Kondo said.

The shop’s primary customer base used to be people in their 60s and older, but with the launch of Shuka, it has expanded to include people in their 30s and 40s.

“I started this brand to pass on amanatto and its culture to the future,” Kondo said. “I dream that people will enjoy the sweet worldwide someday.”

Sense of crisis

Torokuya was founded in 1926 by Kondo’s great-grandmother, Sueno, in front of the Minamiza Theatre in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto. The shop sold amanatto made from toroku beans (white kidney beans) and other ingredients, advertising them with the slogan “miyako meibutsu” (signature specialty of Kyoto).

The shop closed temporarily during World War II but reopened in Mibu shortly after the war ended, with its business style shifting from retailer to supplier to confectionery shops.

Kondo’s uncle, the third-generation owner of the shop, and mother worked at their factory. Kondo, on the other hand, avoided getting involved with the family business at first after a friend in junior high school teased him, saying, “Sweet natto? Nasty!”

The turning point came when he was studying microbiology as a graduate student at Kyoto University.

He helped sell the shop’s products at a temporary booth at Mibudera Temple, near the factory, during the temple’s annual Setsubun-e ceremony. The stall, a long-standing practice that started in his grandfather’s time, drew about 3,000 visitors.

Kondo was astonished by its huge popularity and truly realized that the amanatto business had sustained his family and enabled him to receive an elite education. Encouraged by the customers’ smiles, he decided to take over the family business and repay his debt of gratitude.

After completing his graduate studies, he worked for a confectionery manufacturer for two years before joining the family business at age 26.

Upon realizing that the customer base was aging, he immediately felt a sense of crisis.

“If our shop doesn’t become widely known, neither it nor our food culture will survive,” he thought.

In 2018, he participated in a food event in Italy with the aim of attracting visitors to Japan.

Various gelati made with the syrup and soy milk used in amanatto production is popular with vegans.

At his tasting booth, the chestnut amanatto that he had prepared disappeared instantly. However, the standard amanatto of toroku beans, azuki beans and black beans were left untouched. The experience made Kondo realize that eating sweetened beans was not a Western food culture.

The attempt in Italy was unsuccessful, but Kondo noticed one more important thing: Chocolate and gelato are universally popular with tourists.

“If I combine them with amanatto, people may try them,” he hypothesized.

Kyoto specialty

Kondo took over the business in 2020, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic.

He started work on producing amanatto using cacao beans, which are usually used to make chocolate. He gathered data on water absorption and cooking methods by repeatedly testing recipes and started selling the product online at the end of the year.

Cacao bean amanatto became a hit due to a spike in demand for unusual items ordered online during the pandemic, when people were forced to stay at home.

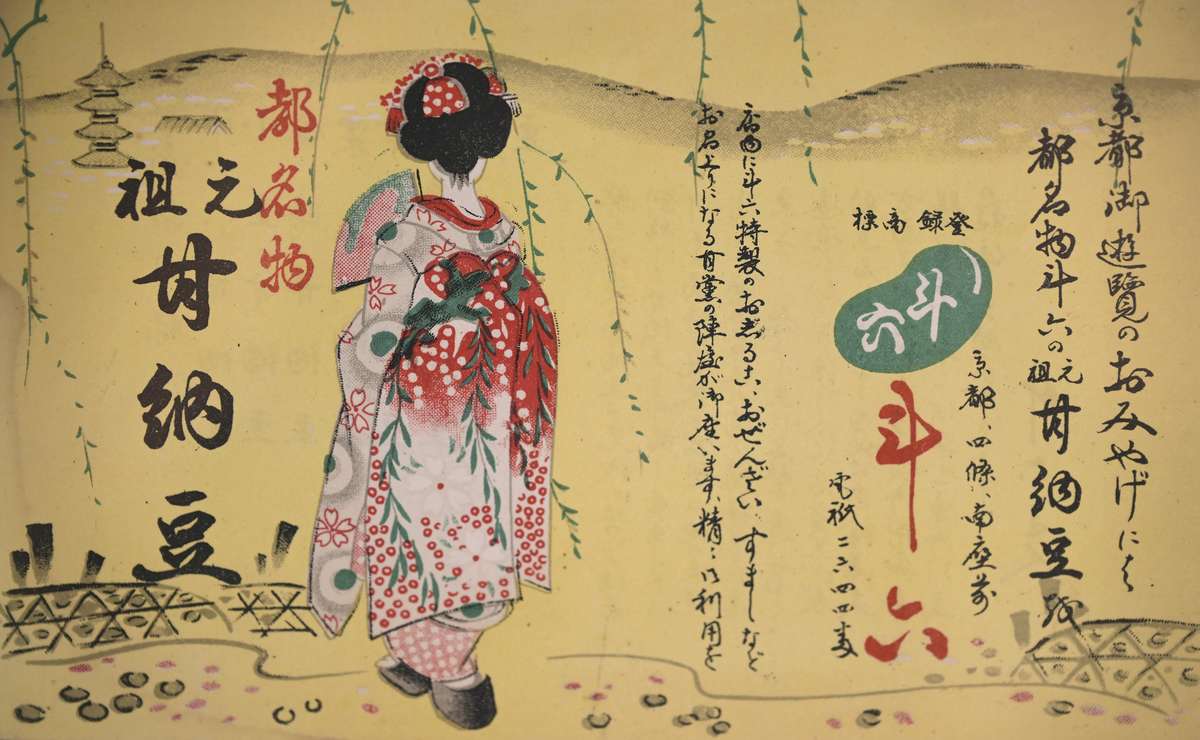

A promotional flyer from the shop’s founding period, which reads “Famous specialty of the ancient capital: Original amanatto.”

He then established Shuka to win a broader customer base and added a cafe to the business’ retail shop.

In 2023, he developed gelato using soy milk and the syrup used to produce amanatto. With the menu having cacao, pistachio and toroku bean vanilla flavors, the shop began attracting international visitors in addition to Japanese customers.

During the nine years since he joined the family business, he has launched a succession of new products. Underpinning his motivation is the spirit that his great-grandmother embodied: aiming for a “signature specialty of Kyoto.”

The founding flyer displayed in the shop proclaims “Original amanatto.”

“There are older shops in Kyoto, so I interpret the sign as telling me to value originality,” Kondo said.

Tradition cannot continue without innovation. He connects the appeal of amanatto to the next generation by offering “evolving amanatto,” which are both new and old.

***

If you are interested in the original Japanese version of this story, click here.

Related Tags

Top Articles in Features

-

Tokyo’s New Record-Breaking Fountain Named ‘Tokyo Aqua Symphony’

-

High-Hydration Bread on the Rise, Seeing Increase in Specialty Shops, Recipe Searches

-

Japanese Students Use Traditional Pickle to Create Novel Wagashi Confectionery

-

My Spendthrift Mother Constantly Asks Me for Money

-

Heirs to Kyoto Talent: Craftsman Works to Keep Tradition of ‘Kinran’ Brocade Alive Through Initiatives, New Creations

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts