The Diet Building in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo, Japan.

8:00 JST, December 24, 2022

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida must have found 2022 to be a tumultuous year. Just five months ago, when the ruling Liberal Democratic Party he leads won the House of the Councilors election, some pundits said that he had a strong political base and that his stable administration would last for a minimum of three years.

But he has stumbled in his handling of many issues, such as the state funeral for murdered former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, inappropriate ties between the LDP and a religious group, and whether to replace certain scandal-tainted ministers of his Cabinet. His approval rate has plunged by as much as 30 percentage points.

Although Kishida has not lost credibility within the LDP and no rival is set to challenge his position, his Cabinet will face a harsher situation next year. This is because he needs to withstand the ordinary Diet session that will begin in January and last for more than 100 days.

The Diet has put a lot of strain on successive prime ministers and has indeed occasionally toppled their administrations. In general, their approval rates have gone down during ordinary sessions, in some instances dropping by as much as 20 percentage points.

Some may wonder how this could be in Japan’s parliamentary cabinet system, in which the prime minister is the leader of the ruling party and is supported by the majority of Diet members. In fact, the LDP and its ally, Komeito, hold about 60% of the total seats in both houses. Why should Kishida need to worry about riding out the Diet session?

One problem is in the Diet’s distinctive parliamentary procedures. In contrast to most European governments, the Japanese government has little power to set timetables or schedules for deliberating on bills. That is hashed out in dickering between the ruling and opposition parties. So, the opposition is given a chance to prolong debates and buffet the administration. If popular opinion is against a bill or a prime minister is in a disadvantageous position, the deliberation time will be dragged out as long as possible, making it extremely hard for the ruling party to manage to bring about a vote to pass the bill.

A minister caught in a scandal is inevitably summoned for tough questioning and criticism. In many cases, the grilling corners a troubled minister into making incoherent apologies which stir anxiety and discontent even within their own ruling party. The administration is forced to decide whether to replace them. Most dismissals of ministers have happened during a Diet session, as we saw with the last extraordinary session, in which three Cabinet members had to go.

All ministers, including the prime minister, are tied down by long deliberations of bills and budgets. Kishida attended committees or plenary meetings of both houses for more than 80 days this year, which was nearly a third of all weekdays. This is not unusual.

Other world leaders attend their own parliaments or congresses much less frequently than their Japanese counterparts. According to research by the National Diet Library, the British prime minster attended about 40 days, the German chancellor 10 days or so, and the presidents of the United States and France just one day each. At a Group of Seven summit several years back, then Prime Minister Abe complained that he had spent enormous amounts of time in the Diet, gaining sympathy from the other leaders.

As written in Article 66 of the Constitution of Japan, “The Cabinet … shall be collectively responsible to the Diet.” Of course, this article stipulates a principle of the parliamentary system — the power of the Diet to check and balance the government. To be frank, this Diet responsibility has been a heavy burden on not only ministers but the whole government. While a budget is being discussed, every ministry finds itself having to stand ready to respond to any question from opposition members until late at night. It has forced government officials to endure long working hours, which may cause young bureaucrats who feel it to be ridiculous and nothing but a waste of labor to leave their jobs.

More than 75 years ago, the Imperial Diet, the predecessor of the current assembly, was like an arena for contention between members of the House of Representatives and the government rather than a legislative organ. This tradition continues even now. It is not rare for a committee discussing a controversial bill to be paralyzed by physical resistance put up by the opposition camps. If the houses are controlled by different parties, which has happened three times in the last two decades, needless confrontations lead to a political morass in which nothing is decided.

According to a poll conducted by The Yomiuri Shimbun last month, the Diet ranked the lowest — at 25% — in response to a question about confidence in domestic institutions. It inspired less trust than the prime minister, the courts, the Self-Defense Forces or the police. It has been one of the most untrusted organizations for more than a decade. Nevertheless, the long-dominant LDP has refrained from fixing the Diet’s outdated rules and customs because it is not easy to persuade reluctant opposition parties to go along. Also, the LDP fears being criticized for trying to steamroll through the bills it wants passed.

When Kishida took office last year, he vowed to promote politics of trust and sympathy. The Diet is completely lacking in both. So, if he wants to deliver on his promise, tackling Diet reforms that have been left untouched for many years is an essential step. He knows the flaws of Japanese politics well enough to be qualified to do this job, if he can just survive the pressure from opposition parties in the next session.

The next Political Pulse appears on Jan. 7.

Takayuki Tanaka

Tanaka is senior managing director, chief officer, administration, of The Yomiuri Shimbun. His previous post was managing editor.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

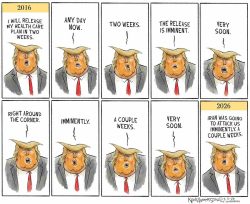

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

Flu Cases Surging Again: Infection Can Also Be Prevented by Humidifying Indoor Spaces

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan