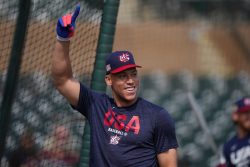

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, center, addresses an advisory panel in Tokyo on Oct. 20.

8:00 JST, October 29, 2022

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has set several goals to bolster Japan’s deterrence capability. One of these goals is to increase the defense budget over the next five years to match the North Atlantic Treaty Organization target of 2% of gross domestic product. Historically, Japan has limited its defense spending to within 1% of GDP. Increasing the budget to 2% will signal a historic shift in Japanese defense policy. No prominent objections to this goal exist within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, although there is debate over how Japan will achieve it.

Kishida aims to achieve Japan’s 2% target by introducing a new definition of defense-related expenditures under the “NATO standard” of accounting. This means that the national defense budget would include some already existing items that Japan does not currently count toward defense spending, such as the Japan Coast Guard budget and the science and technology budgets of other ministries and agencies. Some LDP members fear that the new concept will artificially pad the defense budget. However, these members likely do not understand Kishida’s true motive in introducing the concept.

On Sept. 30, at the first meeting of an expert panel to comprehensively discuss Japan’s national defense capabilities, Kishida emphasized, “We need to break down bureaucratic sectionalism and consider strengthening the comprehensive defense system, by including the use of research and development in the public and private sectors and public infrastructure in the event of a contingency.”

At the panel’s second meeting on Oct. 20, Kishida instructed government ministries and agencies to consider a new framework under which budgets related to research projects and public infrastructure would be counted as defense-related expenditures.

The key concept here is “breaking down bureaucratic sectionalism.” The JCG and the Maritime Self-Defense Force must strengthen collaboration to handle the situation in the Senkaku Islands, where numerous Chinese ships intrude into Japan’s territorial waters around the islands. Discord between the JCG and the MSDF has hampered the operations of both for years. However, the time has come when the JCG can no longer be thought of merely as an arm of law enforcement unsuitable to participate in a Senkaku contingency. A JCG officer recently told me that there are many things for the JCG to do when a contingency happens. And an officer of the MSDF recently told me that the MSDF supports beefing up the JCG. He also hoped that both the defense budget and JCG budget will increase, which is why he strongly supports the concept of a unified defense-related budget.

Kishida also set his sights on research and development spending. The whole government budget for science and technology is over ¥4 trillion a year. The Defense Ministry receives just 4% of that, while the Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Ministry enjoys 49%. Experts point out that there are many fields in other ministries’ budgets that would overlap with defense. But so far, no meaningful collaboration exists between these ministries’ research and development projects and the defense field.

The main reason is avoidance on the part of bureaucracy and academia, both of which fear any association with memories of Japan’s prewar build-up in the early 20th century. At that time, military authorities forced academics to cooperate in developing weapons.

But 77 years have now passed since the war ended. The situation surrounding research and development has changed drastically. In recent years, “dual-use” technology with both military and civilian applications has become more prominent. Major countries, including the U.S and China, now consolidate dual-use research and development under a whole-of-government approach. Japan must do the same.

Of course, the government’s fiscal situation affects these proposed reforms. The ratio of Japan’s general government gross debt, including central and local government debt, to the nation’s GDP is not just higher than that of any other major advanced country — it is the highest in the world. Consequently, the government must prudently shape the budget to be as effective as possible.

Kishida understands this situation well. At the Sept. 30 meeting of the expert panel, the prime minister noted that “even in the event of an emergency, we must prevent the credibility of our nation and the lives of our citizens from being harmed.” A nation usually needs to issue government bonds on the foreign market when it goes to war. Japan did so during the Russo-Japanese War. Still, securing financial resources to increase the defense budget will not be easy.

If Kishida decides to increase tax rates, he will surely face voter backlash. To boost the defense budget, the government must gauge the sentiment of its citizens. Kishida has credited himself with the “ability to listen” to the public. Now, Kishida must demonstrate his ability to persuade the public about the need to defend Japan, and what will be required to do so. Japan’s future hinges on each citizen thinking seriously about these pressing issues.

A close aide told Kishida, “If you succeed in beefing up Japanese defense capabilities, including obtaining counterstrike capabilities, that will be your legacy.” Kishida concurred. The government will revise three defense documents, including the National Security Strategy, by the end of this year. The documents set out the size of the defense budget and the content of the nation’s defense capability. The LDP and Komeito, its ruling coalition partner, have commenced talks on the issue. At the Sept. 30 meeting, Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada stressed: “We have little time left. We must take immediate action and achieve a drastic strengthening of our defense capabilities within five years.” The next two months will be paramount in determining the long-term course of Japanese security policy.

Of course, the government’s fiscal situation affects these proposed reforms. The ratio of Japan’s general government gross debt, including central and local government debt, to the nation’s GDP is not just higher than that of any other major advanced country — it is the highest in the world. Consequently, the government must prudently shape the budget to be as effective as possible.

Kishida understands this situation well. At the Sept. 30 meeting of the expert panel, the prime minister noted that “even in the event of an emergency, we must prevent the credibility of our nation and the lives of our citizens from being harmed.” A nation usually needs to issue government bonds on the foreign market when it goes to war. Japan did so during the Russo-Japanese War. Still, securing financial resources to increase the defense budget will not be easy.

If Kishida decides to increase tax rates, he will surely face voter backlash. To boost the defense budget, the government must gauge the sentiment of its citizens. Kishida has credited himself with the “ability to listen” to the public. Now, Kishida must demonstrate his ability to persuade the public about the need to defend Japan, and what will be required to do so. Japan’s future hinges on each citizen thinking seriously about these pressing issues.

A close aide told Kishida, “If you succeed in beefing up Japanese defense capabilities, including obtaining counterstrike capabilities, that will be your legacy.” Kishida concurred. The government will revise three defense documents, including the National Security Strategy, by the end of this year. The documents set out the size of the defense budget and the content of the nation’s defense capability. The LDP and Komeito, its ruling coalition partner, have commenced talks on the issue. At the Sept. 30 meeting, Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada stressed: “We have little time left. We must take immediate action and achieve a drastic strengthening of our defense capabilities within five years.” The next two months will be paramount in determining the long-term course of Japanese security policy.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Michitaka Kaiya

Kaiya is a staff writer in the Political News Department of The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

Reciprocal Tariffs Ruled Illegal: Judiciary Would Not Tolerate President’s High-Handed Approach

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

Flu Cases Surging Again: Infection Can Also Be Prevented by Humidifying Indoor Spaces

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan