Chronic Issues Erode Thailand’s Economy as Political Confusion Persists, Threatening Terminal Decline in Its Economy

17:32 JST, February 21, 2026

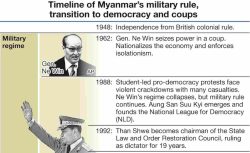

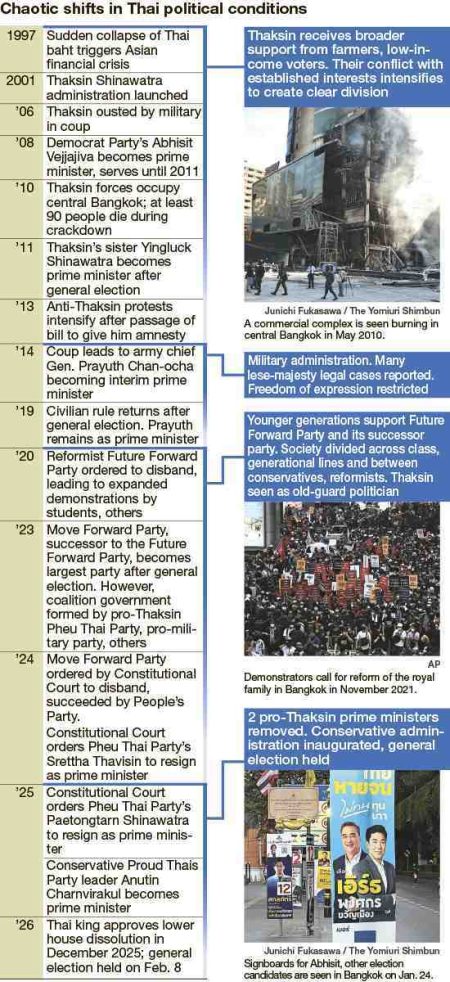

Voting for the House of Representatives in Thailand took place on Feb. 8, as the nation struggles to emerge from two lost decades of political instability. Since the 2006 coup that ousted former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, the country has seen a steady worsening of structural problems, including an aging and shrinking population as well as high household debt. A lack of progress on industrial and trade policies has further fueled concern that the economy is in a state of terminal decline.

A coalition government centered on the Proud Thais Party that won the largest number of seats in the election must work to achieve political stability and resolve structural issues. Thailand stands at a major crossroads — revival or decline.

Since the 2000s, Thailand’s political landscape has evolved into a complex, multilayered struggle. What began as a fierce “inter-class” struggle between pro- and anti-Thaksin factions has been compounded by “inter-generational” tension driven by youth seeking reform, as well as a broader clash between conservatives and reformists.

Rising nationalism, fueled by conflicts with Cambodia, has also become a key factor swaying the nation’s politics.

The 2010 unrest solidified the deep divisions within Thai society. It began when Thaksin supporters occupied Bangkok’s premier commercial district, leading to a crackdown that claimed more than 90 lives. My experience reporting on these events firsthand confirmed this reality.

The pro-Thaksin faction quickly sealed off the city center with barricades, turning a three-square-kilometer area into a fortress. With The Yomiuri Shimbun’s Bangkok Bureau located inside this zone, the office effectively became a front line of the story for a month and a half.

The Thaksin administration garnered enthusiastic support among those long neglected by the political establishment through measures such as debt rescheduling for farmers.

Its signature health care system, which offered visits for just 30 baht (then about ¥100), became a symbol of his commitment to those previously ignored by the government.

A political scientist at Chulalongkorn University pointed out that while Thai people had traditionally accepted a class-based society and sought a path of coexistence, the Thaksin era changed the farmers’ perspective. The scholar noted that during this period, farmers came to understand the concept of rights and realized that elections could be a means to achieve equality.

The occupied district, initially a “battleground” for a class demanding a general election, devolved into a scene of civil strife between armed groups and security forces. The standoff ultimately culminated in a forced dispersal by security forces and the torching of major commercial facilities.

A farmer returning home on a long-distance bus remarked that, on his first visit to Bangkok, he had realized just how developed and prosperous Thailand had become.

Thaksin posed a direct threat to the ruling elite who sat atop Thailand’s rigid class structure. This friction led the military to stage another coup in 2014, ousting the administration of his younger sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, and entrenching military rule for the next five years until 2019.

The Future Forward Party was born out of a backlash against military rule. Its 40-year-old leader, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, galvanized a broad base of support, capturing the imagination of students and the younger generation.

Under the banner of “Thai-style democracy,” factions closely aligned with the monarchy — including the military and royalists — maintain a firm grip on political power. This has created a relentless cycle in which opposition forces are consistently ousted by coups or judicial intervention, even after securing mandates through the ballot box.

The Constitutional Court’s order to dissolve the Future Forward Party ignited a wave of prolonged protests led by the younger generation. History repeated itself when its successor, the Move Forward Party — which had emerged as the top finisher in the 2023 general election — was also dismantled by the court.

Thaksin, who returned to Thailand in 2023, has faced criticism after his proxy Pheu Thai Party formed a coalition with pro-military parties.

Two prime ministers from the party, Srettha Thavisin and Paetongtarn Shinawatra, were subsequently removed from office by the Constitutional Court. Achieving political stability that respects the will of the people remains Thailand’s greatest challenge of the last 20 years.

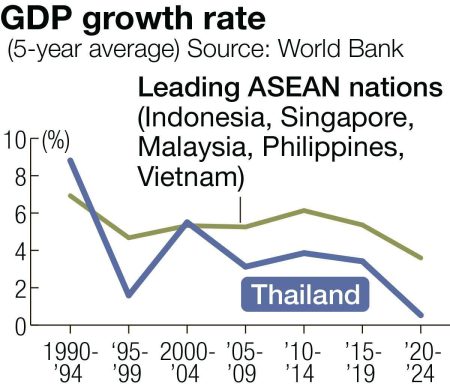

Thailand’s unstable political climate has led to a heavy focus on short-term populist policies at the expense of fundamental structural reforms, leaving the country facing an increasingly severe crisis.

The Thaksin administration, established in 2001, is often said to have left a negative legacy by reinforcing corruption and systems of entrenched interests.

On the other hand, it deserves credit for revitalizing the economy after the slump of the Asian financial crisis through “Thaksinomics,” an economic policy that prioritized the poor and marginalized.

Since Thaksin was ousted in a military coup, however, it is hard to argue that subsequent leaders or the military government have promoted policies that bolster the country’s economic strength.

The Yingluck administration introduced a rice-pledging scheme, with the government purchasing rice from farmers at prices significantly higher than market rates. The initiative, widely criticized as a “handout” from its inception, resulted in a staggering fiscal deficit. Despite the transition to military rule, the reliance on populist policies has persisted as a key feature of Thai politics.

In the 2010s, Thailand became increasingly aware of its declining birth rate and aging population. According to the World Bank, the proportion of people age 65 and over reached 15% in 2024, marking the country’s transition into an elderly society.

Alongside neighbors like Japan, South Korea and Singapore, Thailand is experiencing a significant demographic shift. According to some estimates, the country is on track to become a super-aged society as early as 2029.

Media reports indicate that the number of births in 2025 dropped below 500,000 for the second consecutive year, marking a 75-year low. With the total population believed to have begun shrinking ahead of projections, the country’s chronic labor shortage — previously offset by workers from neighbors such as Myanmar — is set to deteriorate further.

Household debt fueled by mortgages, auto loans and living expenses have also reached critical levels. The debt as a percentage of gross domestic product, which stood below 80% prior to the Yingluck administration, has climbed steadily, hitting the 90% range in the wake of the pandemic.

While financial institutions have tightened lending, the move has backfired, curbing purchasing power and dampening private consumption.

A Thai research institute warns that a recovery in consumer spending could be several years away.

Thailand’s industrial and trade policies are also underperforming. Traditionally, the government has sought to attract foreign investment by offering tax incentives to target sectors.

While Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers have recently increased their presence in the country, it is said these investments have yet to result in significant orders for local suppliers or a meaningful boost in domestic employment.

Only a handful of Thai companies can compete on the global stage. Unless the government prioritizes expanding the base of domestic firms, the industrial structure will fail to modernize.

Another urgent task is education reform, as international assessments by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development highlight a downward trend in academic performance.

The International Monetary Fund predicts that Thailand’s GDP will be overtaken by the Philippines in 2028 and Vietnam in 2030, causing it to slip to fifth place in Southeast Asia. There is even a possibility that the rapidly growing Vietnamese economy could surpass Thailand as early as 2026.

After the World Bank classified Thailand as an upper-middle-income country in 2011, the nation’s economic progress stalled, leaving it unable to reach high-income status.

Somkiat Tangkitvanich, president of the Thailand Development Research Institute, a policy think tank, pointed out the urgency of the situation, stating that Thailand has grown old before becoming rich.

Somkiat warned that at the current sluggish growth rate, Thailand will not achieve high-income status until 2070. He emphasized that without radical policy shifts, the country will remain unable to escape the “middle-income trap.”

Thailand serves as major hubfor Japanese firms

About 6,000 Japanese companies conduct operations in Thailand, more than any other Southeast Asian nation, making it the world’s third largest hub for Japanese business, behind only China and the United States.

After the World War II, Japanese companies began expanding into Thailand in the 1950s and 1960s; in the 1970s they built a number of assembly plants for automobiles, home appliances and other products. These moves, however, were seen as an “economic invasion” by many people in Thailand.

Though it may be difficult to imagine given today’s friendly relationship, when then Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka visited Bangkok in January 1974, about 5,000 students and other demonstrators surrounded his hotel and chanted, “Go home.” The Yomiuri Shimbun reported these developments under headlines like, “Anti-Japanese sentiment worse than expected” and “Southeast Asian diplomacy proves difficult.”

Partly because of this incident, Japan began working in earnest to improve war-damaged relations with Southeast Asian nations. In 1977, then Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda, speaking in Manila, proclaimed the “Fukuda Doctrine,” whose main pillars were that Japan would not become a military power again and that it would build genuine friendships with Southeast Asian nations.

Economic interdependence between the two countries began to deepen starting in the 1980s, when, in the wake of the 1985 Plaza Accord, favorable conditions such as a strong yen led to Japanese companies more quickly expanding their presence in Thailand.

In the 2000s, the administration of then Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra unveiled its “Detroit of Asia” plan, aiming to make Thailand a hub for the automotive industry, which prompted a string of Japanese automakers to establish bases in the country.

The greatest crisis for this expansion was massive flooding in 2011 that submerged seven large industrial complexes. When I visited the area by boat at the time, I found that only the roofs of the plants were visible above the surface of the floodwaters. The effects of the disaster were felt globally, as hundreds of companies halted operations, and even some plants in North America suspended work due to a lack of supplies from Thailand. This served as the impetus for a reexamination of supply chains from the perspectives of disaster resilience and economic security.

Japanese distributors have significantly increased their presence in Thailand since the 2010s as the Thai consumer market has expanded. They are vigorously expanding their operation of restaurants, retail stores and clothing shops, among other businesses, attracting vibrant customer bases even in regional areas.

However, it is important to note that the competitive landscape is changing in Southeast Asia, with Chinese electric vehicle and other companies becoming increasingly concentrated in the region.

Junichi Fukasawa

Yomiuri Shimbun Director and Senior Writer

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan