Hawaiian Students to Celebrate 130 Years of Kabuki in Hawaii with Commemorative Program in Gifu; Kabuki Star Ichikawa Monnosuke Advises

Students practice kabuki at the University of Hawaii in November 2023.

15:00 JST, May 19, 2024

Kabuki has been passed down from generation to generation in farming villages throughout Japan and has always been a popular form of entertainment there, but the traditional theatrical art also found its way to Hawaii, brought there by immigrants crossing the Pacific Ocean. It has since been nurtured there for over 130 years.

Students from the University of Hawaii and others are scheduled to perform jikabuki, a folk performing art in Gifu Prefecture, this June at Aioi-za, a theater in Mizunami in the prefecture. They intend to “return” the kabuki that in Hawaii has overcome such challenges as war, aging instructors and the COVID-19 pandemic to its place of origin.

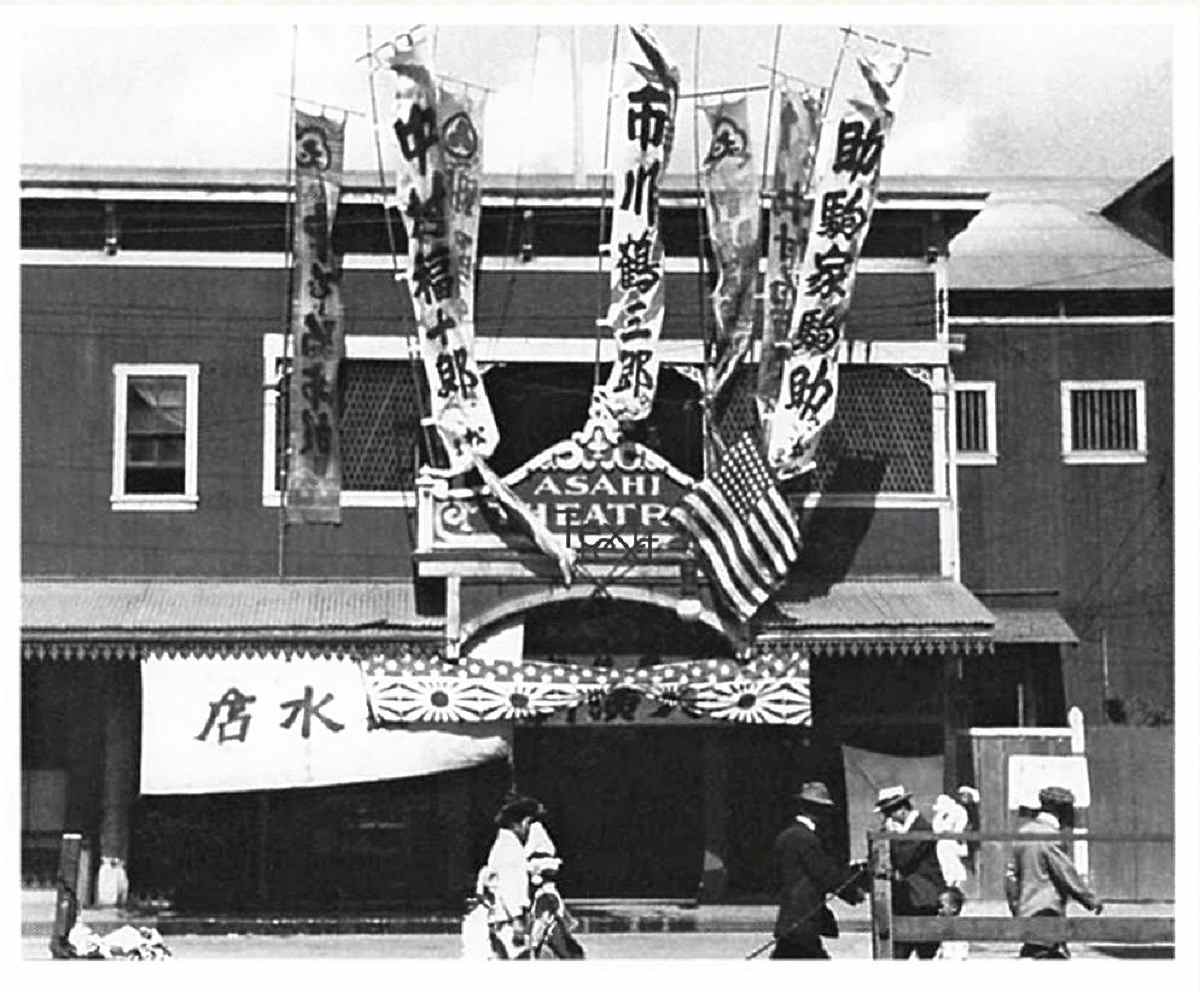

Kabuki has a long history in Hawaii. In 1868, immigrants from Japan arrived in Hawaii and began performing kabuki to entertain themselves amid hours of backbreaking labor. After the first public performance in 1893, kabuki proved so popular that playhouses were built on islands outside Oahu.

In 1924, Japanese American students at the university performed “The Faithful” — the English title of “Chushingura.” At the time, racial discrimination meant that the students were forbidden from playing the roles of white people. It was in that context that they decided to stage their own play.

World War II caused the performances to be put on hiatus. Then in 1951, the university staged its first postwar performance, which was made possible thanks to Prof. Earle Ernst, who had gained a wealth of knowledge from his censoring kabuki scripts in Tokyo for the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers in Tokyo. Ernst can be credited with laying the foundation for theater studies at the university. Other teachers at the university included Japanese Americans who had been involved in local kabuki for many years and kabuki actors such as Onoe Kurouemon and Nakamura Matagoro II.

Kabuki performances, which were staged every few years, continued into the 2000s. However, no performances had been held since 2011 due to the large cost of inviting kabuki actors.

The Asahi-za theater in the 1910s

‘For the next 100 years’

Ichikawa Monnosuke VIII, left, Yukika Soma

It was under these circumstances that famed kabuki star Ichikawa Monnosuke VIII, 64, stepped up to offer his guidance. His wife Yukika Soma, 63, a former student at the university, had long wished to teach kabuki in Hawaii. She contacted Prof. Julie Iezzi, 61, who teaches traditional Japanese performing arts such as kabuki, noh and kyogen, and the two began communicating.

While studying in Japan, Iezzi juggled koto and shamisen practice while earning a master’s degree in musicology at Tokyo University of the Arts — which was previously known as Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. Around the time the Japanese couple contacted her, she was worried about the continuation of kabuki in Hawaii because the Japanese Americans who helped carry the tradition for so many years were getting older.

In 2016, Monnosuke visited the university’s John F. Kennedy Theatre. When he saw things like the hanamachi walkway, which extends through the auditorium, a bell used in the kabuki play “Musume Dojoji,” and the boards displaying the names of the actors, he knew he had to help carry on Hawaii’s kabuki “for the next 100 to 150 years.”

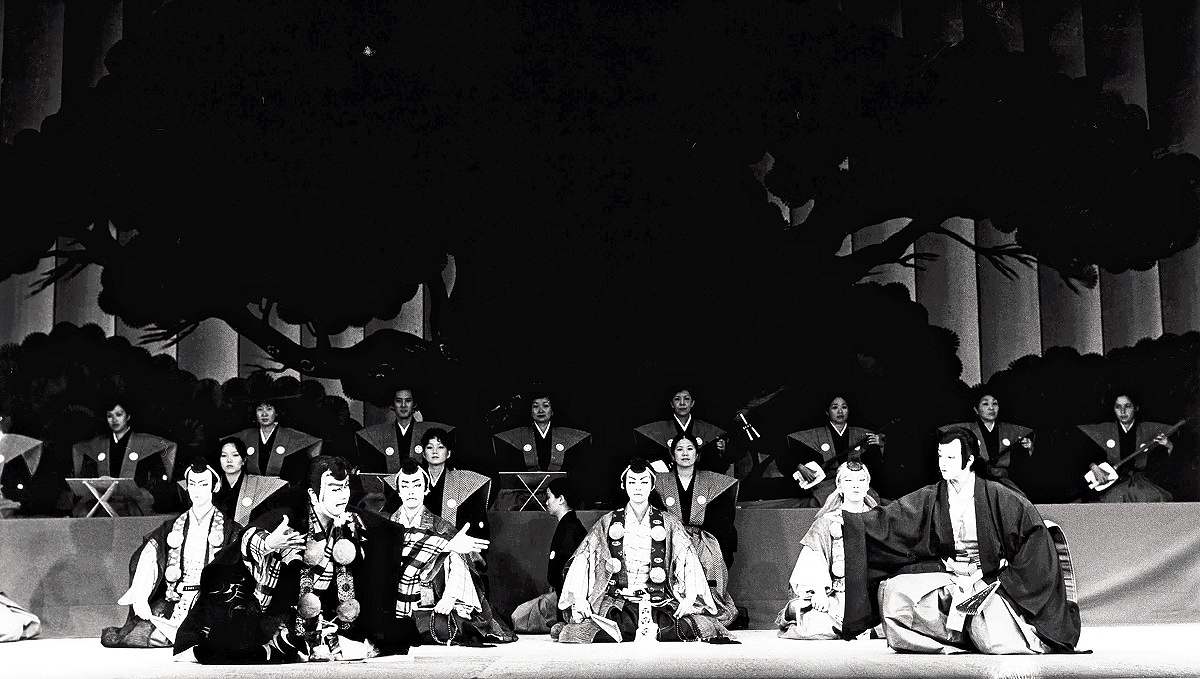

“Kanjincho” is performed at the University of Hawaii in 1981.

Practice held in Japanese, too

However, the planned instructions and performances were postponed due to the pandemic. Last spring, the students who learned about kabuki gradually began practicing, and an audition was held in autumn for the upcoming program.

The program is called “Benten Kozo,” a play strongly connected with the theater’s inaugural performance in 1963. Although the performance will be in English, the students practiced in Japanese before memorizing the English lines to properly pay attention to the distinctive seven-and-five syllable meter.

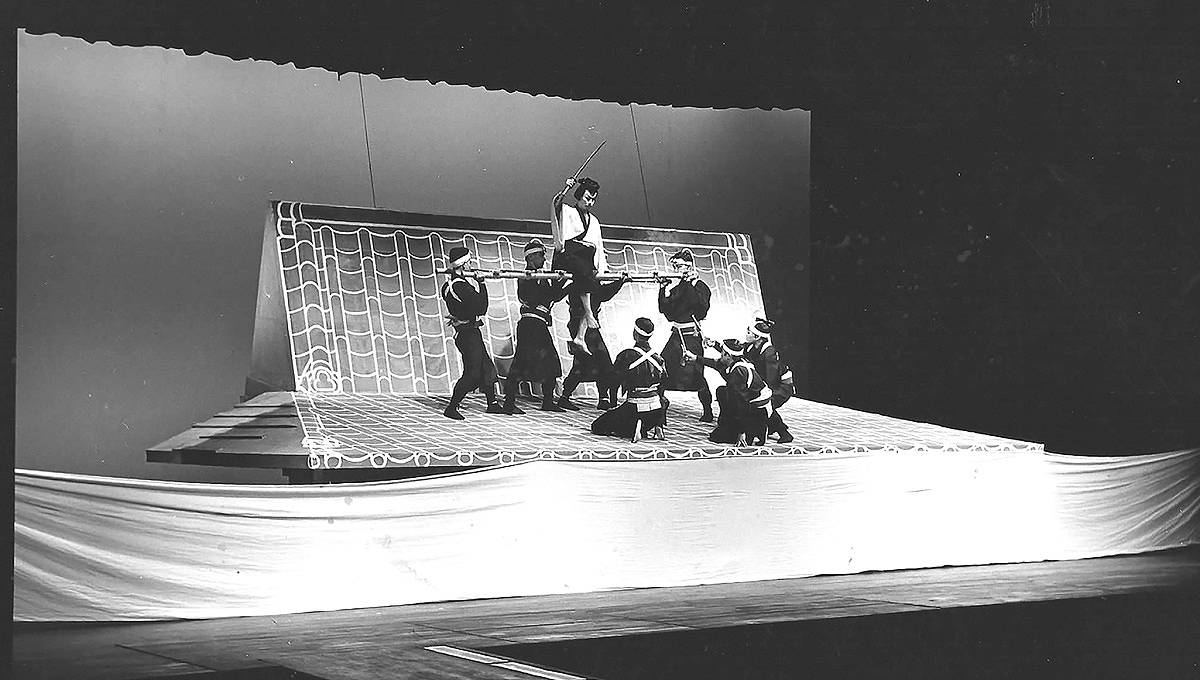

“Benten Kozo” is performed at the University of Hawaii in 1963.

“The students don’t understand Japanese, so rather they listen carefully to what kinds of sounds are being made,” Iezzi said during an interview.

Karese Kaw-uh, 27, a student participating in the project, became interested in kabuki after learning about it when a Japanese exchange student stayed with her family. “I love community development where people can grow closer together through shared experiences,” she said. “My professional goals are to work with communities to celebrate different cultures through art.”

Another participant, Jane Traynor, 30, a native of Canada, said that she goes to a kabuki theater whenever she is in Japan. “I am learning kabuki here in Hawaii because I would like to one day do Japanese theater projects similar to this one back home in Canada,” she said.

Monnosuke has high hopes for the kabuki project, saying, “To promote kabuki overseas, it’s best to get students who will spread their wings and fly around the world to develop a deep appreciation of kabuki.”

Iezzi said she is aware of the long and profound history in Hawaii’s kabuki. “There may be fewer opportunities to watch plays nowadays, but seeing them in the same place and breathing in the same air as other people would be a great experience.”

The kabuki program is scheduled to be performed at the Gifu Seiryu Culture Plaza in Gifu City on June 1 and at the Aioi-za theater on June 2.

“Sukeroku” is performed at the University of Hawaii in 1995.

Top Articles in Culture

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Chofu, Tokyo; Unique, Surreal Works Draw Steady Crowds

-

2 Unpublished Early Novellas by Japan’s Kenzaburo Oe Discovered, Show Budding Promise of Future Nobel Prize-Winning Author

-

Japanese Film, Anymart, Wins Critics’ Award at International Film Festival in Berlin, Director’s Debut Feature Film Shocks Audiences

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

_0001-250x189.jpg)